Selim Mourad was one of the friendliest faces I’ve encountered during the 38th edition of the Cairo International Film Festival. His energy, oozing with excitement and awe at the city –Cairo, the capital of Egypt- didn’t mirror the heavy subject matter which he chose for his first long documentary This Little Father Obsession which translated –impressively- into a different Arabic title The Austrian Emperor. The Arabic title was derived from a scene where the father comments on the son not having kids –because of his homosexuality- with a casualness that could be implying more than it intended; that he was not the Austrian Emperor, so why should anybody care whether he had children.

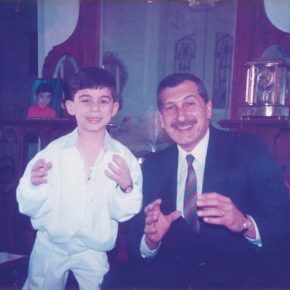

Mourad made a personal film that documented a transitional stage in his life, as well as his family’s. He was just coming out to his family when they had to sell the ancient family home for money to survive. So there was an act of creation and another of destruction; where did a 28-year-old gay Lebanese man find his footing?

“I hate labels. I can’t be saying that I am making a “gay” movie. It is a film where the director happens to be gay. My family history is the main plotline through which my sexual identity happens to contribute to the course of action.”

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=A3nrnB5Uvqk

The film comes during a tough time for Mourad and his family. He was grappling with the idea that he would be the last Mourad. His family ends at him. He found himself at a place where he is even unsure of his willingness to contribute to the Mourad bloodline.

During the film, Mourad sought an adopted Uncle –André- whom his grandfather had adopted when he thought he wasn’t going to have kids. But then his grandfather remarried after his first wife died, had two kids with his new spouse and ended up kicking André out of the house and dismissing him from the family heritage.

“I searched for the adopted Uncle family to try and rub the guilt of being the last Mourad off my skin. I found that he had children and his children had children. It was very weird because in our mind we always thought we were the original Mourads while they were the unoriginal Mourads but as I saw his extended family I became a bit confused on what it meant to be the real son and the substitute.”

Questions like that are deep in action throughout This Little Father Obsession. Selim Mourad received critical comments such as this one from a viewer: “I was disappointed by the film. I thought I would see what gay life in Beirut was like.” But Mourad’s film had a different focus that was both personal and universal. He drew on particular themes that concerned him and yet stretched out to comment on longevity and continuity through parenting. The family tree ended with Mourad because he was gay and couldn’t have children, but now that a possibility of a gay couple adopting is not so far away from the Arab world, would Mourad consider that as a branching out of the family tree. Why so many questions without an answer?

“It’s so boring,” Mourad answers with that wicked smile. His positivity is infectious even though he was being interviewed by one of the biggest pessimists; my humble self. As the film stretched on it was so obvious Mourad wasn’t going to offer easy answers. He made a film that allowed audiences to think and reflect on the life of a man whose life seemed so far away from theirs.

“You’re just like my father,” he commented on my pessimism. In a back and forth scene between Selim and his father, Mourad, the father comments on why his son’s state –as a gay man in the Arab world- scares him. He fears that his son might get killed.

“Things are already dark when you’re normal, so just imagine when you’re not!”

Art communicates Faster than Words

Being an Egyptian who never really got a chance to become acquainted with the Lebanese culture –despite having Lebanese roots- and Mourad being an Arab man who never got a glimpse of the golden age of Egyptian cinema, there was a bit of miscommunication. Most of the time, we Egyptians presume the Arab world to be pretty familiar with our dialect. Egyptian films and TV series are all over the Arab world so they must all understand what we are saying verbatim. Meeting Mourad shook my beliefs to the core and gave me the chance to reflect on what it actually means to understand each other. We resorted to using the universal English tongue to try and get out of certain irksome situations. He asked for kabees and I thought he wanted a heavy, fatty meal. But turns out kabees is “pickles” in Lebanese dialect which translates into mekhalel in Egyptian dialect!

Miscommunication hovered over how (some) audience members perceived Mourad’s art. Many people went into the cinema expecting a scandalous film, a stereotype of how they expected young, gay Lebanese men to live their lives. What they saw was a prolonged, serious tale that stretched out for longer than anticipated.

This Little Father Obsession and the Queer Gaze

The film represents a very rare and positive queer gaze, rarely seen in an Arab film, within an industry infested with heteronormativity and –sadly- misogyny. After legendary Egyptian queer director Youssef Chahine, a queer gaze becomes more of a token than a surprise. It wasn’t his conscious decision while making the film of course, but still he doesn’t give a definitive answer to where he actually belongs;

“I can’t say that being myself takes us away from the regular male gaze, but I don’t know if it makes us enter into the queer gaze.”

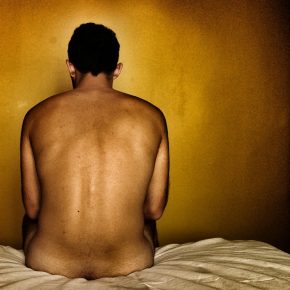

From what I see, Mourad’s treatment of his subjects; male and female, takes us away from a heteronormative treatment of a person in front of the camera. His nudity, a stark and refreshing realization of the “self” rather than an exposure to satisfy and titillate the male gaze, becomes a testament to what’s gay and what’s not, at least in the eyes of a regular viewer.

“The naked scene, to my father it meant being “gay” right in the face. All the while he and my mother treated me like a baby ever since I came out. My father never asked me about my sexual life so for him this scene was my admission of being gay. Maybe if I were straight he wouldn’t have reacted that severely.”

The nudity in Mourad’s film wasn’t just an excuse for the actor/director to take his clothes off. It was more of an artistic expression both thematically and metaphorically. In one scene, Mourad lies naked while ghosts of his ancestors in different costumes pertaining to varying eras huddle around his body. Mourad throws back the inspiration behind the sacrificial image to religious iconography in churches. It could also be a tribal image precipitated into his mindset through ancestors he never even met. In another striking shot, his father and mother cry tears of blood, Selim also recites the image of the Virgin Mary crying tears of blood as one of the biggest influences behind that scene. Mourad’s sense of humor could be clearly seen through his mix of religion and nudity. He also sees it as a testament to how kids have grown out of their parents’ restrictive asexual cocoon of faux safety. To his parents, he had probably been always perceived as Selim the kid; even after coming out. But his nudity is the queer guy coming out of the closet in the literal sense; stark naked, unrestrained and uncontrollable.

Always a Question, Never a Resolution…

Despite the film ending in a graveyard and dealing with heavy subject matter such as infertility, destruction and dysfunctional familial ties, it really has a positive undertone that seeps through. Not a single moment did I feel burdened by the heavy subject matter or was unable to sit through even with the very impressive 104 minutes length. It felt as if –like the family- I was waiting for a resolution that never came. A possibility that never reached the surface?

“Gay people are –theoretically- not supposed to procreate,” Selim comments, “just to be the best versions of themselves. If I am straight and my name is Q, then I’m supposed to have kids and allow them to become R, S and T. But if I’m gay, then I’m supposed to make the transition in-between those letters from Q to R, S and T on my own. This is why the queer journey is much more loaded from my perspective.”

What strikes a nerve in This Little Father Obsession is how it uses its creator’s sexual orientation to reflect and reject standard patriarchal norms through its core ideology –continuity through the preservation of kind and name. I saw it as a very “Arab” film that dealt with the patriarchal norms of fathers giving blood and name to sons, while Mourad wondered if it had a more universal aspect to dealing with patriarchy in general. In providing a work of art with no resolution whatsoever, Mourad not only allows his handling of the subject matter to prevail, but in questioning even his own MO, he gives way for speculation and dissertation, which challenges the archetypal depiction of a man’s sexual conflict on the screen.

Being Selim Mourad…John Malkovich Style

Mourad and I rarely agreed on anything regarding This Little Father Obsession which brought me to the brilliant quote by American playwright Arthur Laurents, “Nobody really sees the same movie.” What I perceived as a female living within –the narrator Carole Abboud, who is Mourad’s friend, producer and actress- was his idea of having conversations with the dead sister whom he never knew. It could be the same but for a male director to have a female alter-ego, let’s take a deep breath and reflect on this for a second. Not only does he defy patriarchal norms, but the thin line between genders is also crossed. If his dead sister was his other self, than how much of Selim Mourad was male or female? Where did the gay man stand from the child yet discovering who he was and where his place in the world could be? What about the female self? What did it represent? Does it require us a queer gaze to discover the otherness within our gender-defined selves?

Mourad’s other films -six shorts of varied lengths- have underlying themes of death, religion and sexuality connecting them all together. Mourad is of Christian upbringing. It is so easy to notice how religion suffused its way into his films, both as a constant presence as well as a background to a less restrained, sexual foreground. The mise-en-scène in more than one film reflects a certain “Selim against self” conflict where everything he has been fights with the young man he is trying to be.

Selim Mourad draws from within himself a rich, complex world. Sins of the fathers tag along in his documentary This Little Father Obsession, but they don’t define the sons. Talking to him –and writing it all down- was a grueling task, only made harder by the sensitivity of his artistic expression and his attention to detail. In the end, though, one compelling work of art has been documented and secured in my memory as a writer forever, hopefully preceding many more from this fresh-faced, Lebanese talent!