Memoirs of Jumaboy Allaberganov

(Recorded by his granddaughter Muxlisa Khaytbayeva)

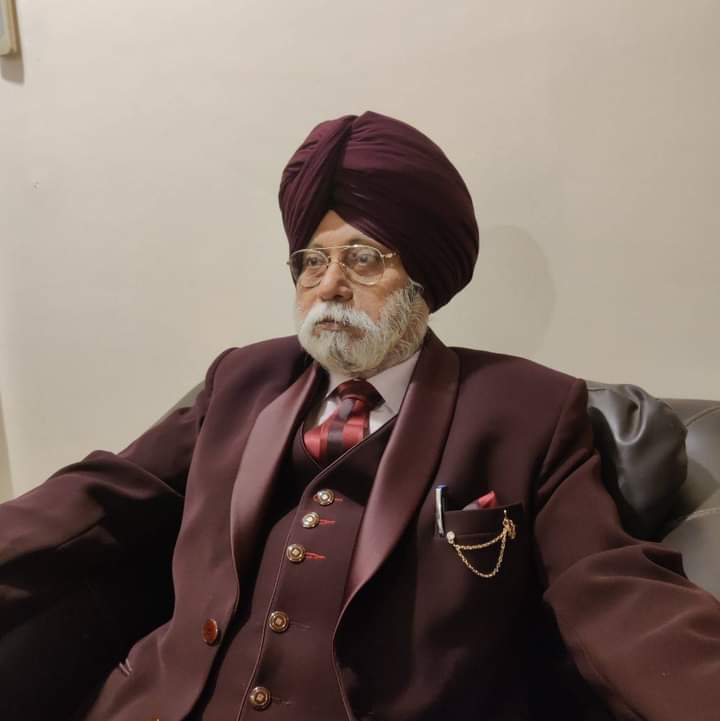

First of all, I must say that it gives me great pride to speak about our intelligent friend and contemporary, Omon Matjon.

Omonboy and I studied at the same school. He was a very diligent student, passionate about literature and history, and loved reading books. I can’t recall a time when Omonboy was just idly playing in the streets. He was always seen flipping through a newspaper or a book. He would somehow persuade his father to buy him new books, no matter how difficult it was.

He constantly engaged our school’s history teacher, Mr. Do’simmat, with various questions and eagerly sought answers. This curiosity is clearly reflected in the works he wrote later in life.

He loved his homeland deeply and beautifully expressed the history of Khorezm through legends and stories.

Thanks to his great talent, Omonboy earned everyone’s respect while still in school. His poems and articles regularly appeared in the school’s wall newspapers. Nearly all the students knew his creative works by heart.

He quickly became the pride of our school. His first poem was published in the district newspaper under the title “The Fish and the Rotten Net”:

The fish and the rotten net,

Quarreled hard, you bet.

Said the net: “Hey fishy boy,

You’re in trouble, you’ve lost your joy…”

After that, his poems began to appear in various publications one after another.

Even during his military service — this must have been in the 1960s — his poems were published in the journal “Sharq Yulduzi” (Star of the East).

All of us peers felt great pride in his achievements and rising fame among the people.

Omonboy entered the world of literature in 1965–66. To see him sharing the stage with such great poets of the time as Abdulla Oripov and Erkin Vohidov, enriching the literary garden, was a double joy for all of us.

Today, Omonboy is known to the entire nation as Omon Matjon. He became a prominent representative of the Matjonov family from the village of Bog‘olon, and through his work, he made our village known around the world.

His poems quickly gained popularity.

Who from our village does not remember the following lines?

“Even if autumn strews the roads with leaves,

Even if snow covers the whole world,

Even if spring bursts forth with joy,

One day, I will cross your door.”

With his sharp pen and rich creative legacy, he continues to delight our people.

At the same time, Omonboy played a key role in planting fruit trees over nearly 500 hectares of land in our village, helping transform Bog‘olon into a true land of orchards.

In 1988, we brought fruit saplings from Andijan and together established the “Yoshlik” (Youth) Orchard. It was during this time that I truly realized just how deep his respect was for his birthplace and native village.

Overall, Omon Matjon has been serving our nation and people with great devotion through his noble deeds.

The library operating in our village today also bears his name. He has gifted readers a vast spiritual legacy.

As a People’s Poet of Uzbekistan and winner of the Hamza Prize, our fellow villager Omon Matjon has become a beloved and respected figure thanks to his diverse creative activity and great achievements.

In my opinion, when Omonboy writes about our village, it feels as though he is putting into words the emotions and thoughts we ourselves could not express — and doing so beautifully, simply, and most importantly, deeply.

That is why we hold such deep respect for creative people.

There is no doubt that his works will live on forever and will continue to hold a special place in the hearts of readers.

Khaytbayeva Mukhlisa Mukhtorovna was born on July 11, 2004, in Yangibozor district, Khorezm region, Uzbekistan. She is currently a third-year student at the Faculty of Philology and Arts at Urgench State University, named after Abu Rayhon Beruni.