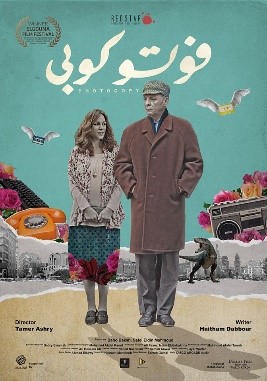

In 2017, I went to the cinema to watch an Egyptian movie titled Photocopy which stars two middle-aged actors playing the roles of an elderly couple, finding love and a way of remembrance in the old streets of Cairo.

The film was beautifully written, acted and directed. It strayed off from the inadequacies in which the nostalgia movement was embedded; it was neither romantic nor sentimental but a character study of a decently educated man who grew up alone in lower-middle-class Cairo and was afraid of extinction.

Mahmoud “Photocopy” as his neighbors call him is a 60-year-old man who owns an ancient photocopier machine, providing services such as typewriting and stenography for the neighborhood. His daily life is intercepted by a young man who asks for his typewriting skills regarding scientific research that he is preparing about the extinction of dinosaurs. This strikes a chord with Mahmoud who begins questioning his identity and the basis of his own existence especially since his feelings for his cancer survivor neighbor, the beautiful aging Safiya, begin taking a different toll.

I read an article somewhere about how writing is about to become an extinct profession since printing paper is almost going to become scarce in the future and printing will not be as abundant as it is today. And I thought to myself; if writing became extinct, what would that make me?

Since extinction was a major theme in the plot of Photocopy, I looked around until I found Haitham Dabbour’s –the scriptwriter- contacts and what began as an interview regarding Photocopy turned into a conversation with a fine intellectual about fatherhood, extinction and the art of the written word.

“I am excited about this interview because it is not a classical, monotonous one, but more of a conversation. I prefer [reading] this type of essays because it makes me get inside the head of the person being interviewed and thus he or she appear closer than they really are,”

Dabbour started the conversations with a warm welcome, expressing his enthusiasm. This was the first gate through which I entered his world. Dabbour was a fan of analysis, character studies and peeling layers off people. This was evident in his short story collection Vivid imagination – Eshy Khayal as well as his two feature films Photocopy and Gunshot – Eyar Nary.

“I am also impressed that you read the books of the writer whom you interview, which rarely happens these days. People who read are rare these days, not just in Egypt but worldwide. Reading and comparing literary and film adaptations, researching your interview subject and discovering my satirist bibliography, all these are factors that excite me about this interview.”

I asked Dabbour about his favorite genre or writing format, and to that he replied,

“I love experimentation and I write different literally and artistic forms. I wrote satirist books that became bestsellers and were sold everywhere. I wrote poetry and won the Ahmed Fouad Negm Prize for colloquial poetry. I published two short story collections; one of them included a story which was adapted into a short film titled Single – Fardy starring Khaled El Nabawy –Egyptian actor of International fame- and the other collection Vivid Imagination contained the short story from which my feature film Photocopy was adapted. After a while, the challenge comes down to; do I write something that I guarantee will become a bestseller or do I write something that would appeal to people? The easiest thing in the world is drifting into the idea of creating bestsellers and thus making more and more of them. However, I am certain that you write because you have something to say not because people force you or semi-manipulate you into writing it.”

Dabbour is a very precise and calculated personality, but his answers are lengthy and rich, like a bowl of creamy soup. Yes, all the ingredients are made en pointe, but it takes a while to absorb the taste and finish the bowl;

“My writings blend elements of magical realism into the narrative. Take for example Vivid Imagination, all stories blend elements of strict realism while breaking the logical limits of living. Imagination gives reality a magical element. My background as a non-fiction essay writer and investigative journalist is prominent through my first short story collection Horseback – Dahr El Khayl which handles reality through a different aspect in addition to adopting a condensed writing technique which describes daily routines from regular lives.”

Talking to Dabbour fascinated me and presented a great opportunity to get inside someone’s head rather than simply laying out carefully prepared answers. Photocopy deviated from the mainstream scene in the Egyptian filmmaking platform nowadays, so I had to learn how the creative process became a reality rather than an ambitious project;

“For 5 years I had been searching for a producer. During that time I wrote scripts for some of Egypt’s most successful comedic and satirical news programs such as The 25th Hour News program –where Akram Hosny presented the iconic comic character of Sayed Aby Hafiza– and the Arabic version of SNL. Even now, I do not consider starting my film career with a commercial, light comedy movie insulting. However, I made Photocopy because I knew I had a story to tell. I also wanted to break the mold into which I was cornered [comedy and satirical writing]. That’s why I knew that the road would be long to make this movie, whether to convince a producer to back it up or a director to put his name on it. My bet while writing the script for Photocopy was on creating a film that would stand the test of time, same goes for Gunshot –I have two feature films now to my credits- and the result was satisfying. I bet on the winning horse by creating these two films.”

Before questioning Dabbour about Photocopy I read the lengthy, short story from his collection Vivid Imagination from which the film was adapted,

“The story and the film adaptation are both different from each other. It’s easy to create an existential theme or mood on paper, but to translate that to the screen; it would require visual and emotional elements. That explains the genre in which we decided to adapt the film into; a sweet, slice-of-life drama which is a rare genre that builds up its characters through combining slices of their daily lives into scenes. The idea of the hero’s journey from the perspective of a regular guy, and yet you [the audience] are interested in following his journey. This rarely happens in Egyptian cinema. We were excited about adapting that concept and were certain that people would be interested in watching it whether on the big screen or through the television premiere. I wanted to create a film that does not go “extinct”. One that stands the test of time. There are films that are consumed only once, and that was what I was trying to avoid. Until now, a year and a half later, people are still talking about Photocopy. There are memes on social media, we are still receiving awards for it. While writing the script, I separated myself from the fact that I wrote the original story. I looked deeper into the characters to discover things that I did not envision originally while writing the story. I worked especially harder on developing Ashgan’s character –which became Safeya in the movie, and this developed the love story between the two protagonists while reflecting the ominous sense of extinction that plagued Mahmoud’s thoughts. It was difficult for me as a young person to sense how an older man would be scared of vanishing from the face of the Earth; the idea of survival beyond death was Mahmoud’s main conflict and what I focused on while writing the script.”

In Photocopy, the protagonist Mahmoud practiced an ancient profession, one that became extinct these days after the era of digital publishing. He was a sub-editor in the News Gathering and Dissemination department in a newspaper agency that recently became digitized. I wondered how Haitham was introduced to such a unique character aspect, and whether he knew people like Mahmoud and thus became inspired to write about their lives;

“I spent years of my life as a non-fiction essay writer and investigative journalist. So I was surrounded by people who worked in the News Gathering department such as Mahmoud. I met different people on different levels and this created a vault inside me filled with interactions and characters that I could go back to whenever I needed inspiration.”

Dabbour is infatuated with details up to the smallest thread, including phonetics, referencing one of the greatest examples in Egyptian art history; Umm Kalthum, who paid attention to the musical sound of words while picking her song lyrics, altering verses in poems so that they would have an easier, auditory appealing sound;

“Safiya is an easier name to pronounce than Ashgan which was the original character name in the book. Pronouncing Safiya would create a nuanced, soft feel for the female protagonist. The combination of the s and f sounds are phonetically superior to the sh sound. I am also a poet so understanding the rhythm and flow of the words are of high importance in my writings.”

It is always refreshing to find a director enthusiastic about a movie that strays from mainstream Egyptian cinema nowadays, which is the reason behind questioning Dabbour about Tamer Ashry, the director of Photocopy,

“I worked with Tamer Ashry before on documentaries. After Photocopy we worked together on a short titled Eyebrows which won the gold star award in El Gouna Film Festival – 2018 as part of the short film competition. We were accustomed to nominating actors for the assigned roles together. This is one of my favorite aspects of working with Tamer, we discuss everything, although the final decision is usually left to the director.”

Big names in the Egyptian film industry were attached to Photocopy. Veteran actor and chameleon Mahmoud Hemeda –who previously played the role of Yehia Shokry Mourad in Youssef Chahine’s semi-autobiographical film Alexandria-New York– played the protagonist, and sultry actress Sherien Reda played the role of Safiya, shedding off her sex icon image and playing a cancer survivor in her 70s who holds onto the simplest pleasures of life. Their romance was bittersweet and their chemistry was magnanimous. I had to ask Dabbour about his choosing actors for the main roles;

“We sent the script to Mr. Mahmoud Hemeda and he replied within 48 hours setting a meeting with us to understand what we have in mind. This was our debut feature –Tamer and I- so he wanted to discuss it further with us. I have to be honest with you, Safiya’s role was hard to cast. Actresses usually avoid these character types; an aging, sick woman, who looked her sickness. The producer Safiy Eldin Mahmoud was the one who suggested Sherien and Tamer [Ashry] saw impressive acting capabilities in her. So we bet on her.”

Music is an integral part of Dabbour’s films, in his two features the role of the soundtrack was more than a complementary element to the key plot and narrative elements,

“My interest in music is part of my interest in the mood of the character. My character profiles always include what the character likes to listen to frequently, what they hum on a regular basis. It is part of the character structuring process, even if it is not part of the script, you have to think of what the character would listen to in their spare time, also how does he or she get angry, how does he or she get into a fight.”

In Photocopy, one of the key defining traits of Mrs. Safiya was her infatuation with one of Farid El Atrash’s –the late legendary Lebanese singer and music composer from the golden era of Egyptian cinema- songs; which was technically a cover that he made for a song originally by another Egyptian female singer. I had to inquire about Dabbour’s use of this particular singer,

“I believe that Farid [El Atrash] is an extremely underrated artist. He did not receive the media exposure that he deserves with the new generation. I found it an opportunity to remove the caked dust off his magnificent musical pieces. It pleases me immensely when younger people mention how they researched the cover of “The key to my Heart” by Farid El Atrash which we used in the film. If you search on Twitter using the verse which is not in the original song and only in Farid’s cover, you will find that multiple people are tweeting about it. Actually, this song deserves all this hype. I personally love it.”

(Official Poster for Gunshot – directed by Karim Elshenawy)

Dabbour’s second feature was the exact opposite; a neo-noir set in the post-2011 chaotic Egypt, adopting a multi-narrative tone and yet retaining some of his key style determinates such as;

“Gunshot was made with the intention to stand the test of time. It fared much better than Photocopy at the box office, and I am sure it will even gain a bigger following after premiering on satellite TV channels, and people would connect to it although it is the complete antithesis to Photocopy. Gunshot is a neo-noir crime drama; a dark movie that poses questions deeper than your average thriller.”

By the time I interviewed Dabbour, the attack on his film Gunshot has been tremendous. Multiple people accuse it of being “anti-25th January revolution” although it cleverly provokes viewers by asking controversial questions regarding all people who participated in the 2011 revolution. In Arab countries, every single person who dies violently or in an accident (whether a Muslim or a Copt Christian) is considered a martyr.

The 25th January 2011 revolution particularly glorified and debauched certain people. A new societal category emerged to include “martyrs” i.e. people who lost their lives during these violent times. The ambiguity of the term in addition to its religious connotation caused a stir between different social tropes in the Egyptian society.

Dabbour’s Gunshot dares to stir stagnant waters by questioning whether every person murdered during an uprising or times of political unrest should be considered a martyr;

“I wanted all the loud voices to calm down before I talk about Gunshot. On a commercial level, I believe that the film has been successful. It challenges the concept of claiming a monopoly over the truth; thus the accusations that it received. On the contrary, people who claimed to own the truth and accused the film of betraying the January [25th] revolution represented what the movie’s protagonist went through. We [filmmakers] expected that and even joked about it while shooting. I recommend Egyptian veteran film critic Mahmoud Abdelshakour’s essay about the film, which not only praises it –as one of the best Egyptian films in 2018– but deeply unfolds the multilayered narrative. Unfortunately, many critics took the film down an unnecessary route of political correctness rather than decipher its morally ambiguous tone. The aim was to discourage people from watching the movie in theaters. Thankfully, this didn’t happen. The film grossed 8 million EGP in a dead season – mid-October. I am betting on broader exposure for Gunshot when it screens on TVs and in other film festivals. The same happened with Photocopy. It was not an instantaneous success but it grew on people by time. This is what I am aiming for. Audiences rarely remember how an old black and white film fared at the box office. The key to success of a film is longevity beyond the release date.”

Dabbour’s POV is en pointe but hard to maintain. Most of the Egyptian filmmakers of the late 2010s eye the box office numbers rather than the period through which a film stands the test of time. He brought examples of two films from the golden era of Egyptian cinema; Angel & Demon – 1960 and Zizi’s Family – 1963; both were not box office successes but they are still all-time favorites in the hearts of many Egyptians. To make the image clear for a Western viewer, think of how It’s a Wonderful Life – 1946 is still enjoyable to this date; generations apart.

“If you watch Gunshot today, it will differ from when you watched it a year ago. I am almost certain that one year later you will see it in a different light. It’s a multifaceted work of art and that’s how we intended to make it.”

I was particularly intrigued by the attention to detail which Dabbour used to craft the forensic pathologist’s character. An alcoholic that slips alcohol to his daily water intake under the noses of his supervisors, Dr. Yassin is fascinated by the dead, to the extent of stalking their posthumous Facebook profiles and sending them friend requests. I had to know where Dabbour found the inspiration for such a fleshy character,

“I have always been fascinated by forensic medicine through my line of work as a journalist. It is a dark, suppressing world that has rich visual, auditory and olfactory elements. It oozes with formaldehyde. I tried to reflect on the current status of the society where people make friends online and IRL. Dr. Yassin is no different from anybody else. He just hates the living. So he tries making new friends with the dead whether IRL with the corpses while performing a post mortem or by stalking their posthumous profiles on Facebook. The dead are his comfort zone and his edge as a forensic pathologist to investigate the causes of death.”

The trick with Gunshot, in all its neo-noir, post-mortem gloom is how to walk the thin line between the right and the wrong. It asks questions that no film before dared to tackle. Its moral ambiguity and the ending which indicates the defeat of truth in front of the mass belief in a lie are both shocking and bold, considering the subject matter; the 25th January revolution which has been glamorized by a part of the Egyptian public and demonized by the other half,

“People hate confronting themselves, which is why Gunshot hit a nerve with its bravery in asking the difficult question; do ends justify means? If being corrupt for a greater cause is a necessity, does that validate corruptness? Political events are created by people and not angels, which is why every political dilemma is open to multiple interpretation scenarios. Nobody holds the obsolete truth. Look through history you will find a lot of political immoral actions that had to be done to achieve noble causes. The question remains: was that justified? It could have been much easier to treat Gunshot like an investigative thriller without layering it with the morale we had in mind. However, Karim [El Shenawy] the movie director and I wanted to make a neo-noir with all the consequential complexities.”

By examining both his features Gunshot and Photocopy, I wondered how strange it must be to make that dramatic of a transition between genres,

“They are both two entirely different films on both technical and aesthetic levels. The script, dialogue, tone, and scene rhythm vary between both films. This is the key to filmmaking, the adventure of exploring different creative projects. You cannot make a feature film easily these days, so you should make one that you are proud of. A film that would stand the test of time and ten years later someone could go back to and write a fleshy critical essay about it.”

For Dabbour -whose last name is the Arabic word for wasp btw- creating short films meant a completely different platform than features. When you watch his shorts Single and Eyebrows you could easily discern how careful he is to separate different platforms from one another; he writes carefully with the limitations and defining features of the medium in mind, and fully understands how to uniquely identify each medium through the elements which he uses uniquely for each project.

“Single –which was originally a short story from my collection Horseback– is the story of a man whose personal space gets smaller and smaller. His sense of freedom shrinks through the intrusion of people around him. The protagonist is a Coptic man who is unable to publicly express his unease at the Islamic duaa that his neighbors installed in the elevator, and which invades his personal space on a daily basis. This represented my first collaboration with Karim [El Shenawy] the director, the megastar Khaled El Nabawy, as well as veteran Egyptian actors Sayed Ragab and Khaled Bahgat.”

I highly recommend watching “Single” through this YouTube link:

As for Eyebrows –I am personally fascinated by Dabbour’s precise short English translation of the movie titles- this is a totally different story. Eyebrows is a brave short that describes the extremist religious “mindset” through a simple situation. A girl from an extremist Salafi upbringing wearing niqab (face covering) wants to pluck her eyebrows which are considered haram from an extremist Islamist point of view. Throughout the short, she struggles between the desire to be accepted as a woman, and her fear of God through an extremist religious viewpoint, which contradicts a once-liberated friend who became even stricter as a religious newbie.

“Both shorts –coincidentally- contain plotlines regarding man’s relationship with religion. Eyebrows differs in the way we tackled the topic at hand; not as outsiders [this has been one of the highlights of the feedback that we received whether in film festivals or juries] to the niqab-wearing community. We used their terminology and adopted their POV to reflect their mental and sociological crises and the contradictory outlook on which they base their religious beliefs so that it always supports the male dominance and leadership of the society to fulfill their role of maintainers and protectors of women. A woman could pluck her eyebrows if her husband approves it but if she is not married, then she is forbidden from doing so. But on what basis? A woman finds herself in a loop. This all reflects the efforts that are being made in objectifying women, by controlling the fine details in their lives, they undergo massive identity, social, and humanitarian crises, which all lead to the unacceptance of their “self”; their feminine identity.”

In many of his films, Dabbour blends themes of absent fathers and patriarchy. The lost “father figure” or the man searching for immortality through having a son could be seen in multiple characters. In Photocopy, the relationship between Osama and Mahmoud could be seen as a rebound relationship for the figures that they both lack in life respectively; a father and a son. In Gunshot, Yassin’s rebellious attitude against his father’s image is a manifestation of the complex concept of the death of the father (as a symbol of patriarchy) and the death of the god in Nietzsche’s philosophy.

I asked him how fatherhood changed him personally, in terms of both artistic and personal values;

“Being a father is a reflective experience of your reckless attitude as a son. Fatherhood makes you reevaluate your life as a son. It resembles writing the same story from the opposing POV. I still have a lot to discover, since I am a father to a 5-year-old son; Zein and my experience has a long way ahead to simmer. I have not only changed as a father, but aging into my thirties changed the dynamics into which I handle my relationships with others. I’m a familial person by nature, but growing old (and becoming a father) made me grow closer to my father and more sympathetic and understanding of his feelings. I tried translating all the details into the paternal relationships which I represented in both my long features.”

At the end of an enriching conversation, Dabbour gave me writing advice, which I am feeling compelled to pass on to future generations of writers,

“Writing does not have a manual. There are no clear steps on which you must tread to be considered a good or a bad writer. Writing is based on individual differences in style and context. However, my personal belief is that daily jobs never hinder creativity. Naguib Mahfouz –one of the greatest Egyptian writers of all times– remained a government employee all his life, Ibrahim Aslan was a 9-5 employee. I used to have a daily, fulltime job as a journalist for 10-12 hours per day and it never stopped me from creativity. The only thing that you need to sustain are 12-15 hours weekly dedicated to writing. Before starting a writing project, try to set a hypothetical deadline which would prevent you from succumbing to feelings of guilt in case you fail to deliver the project in time. Writing is a serious relationship that loses intensity as time drags on. The key is to keep that fire ignited at the start of the project as alive as possible.”