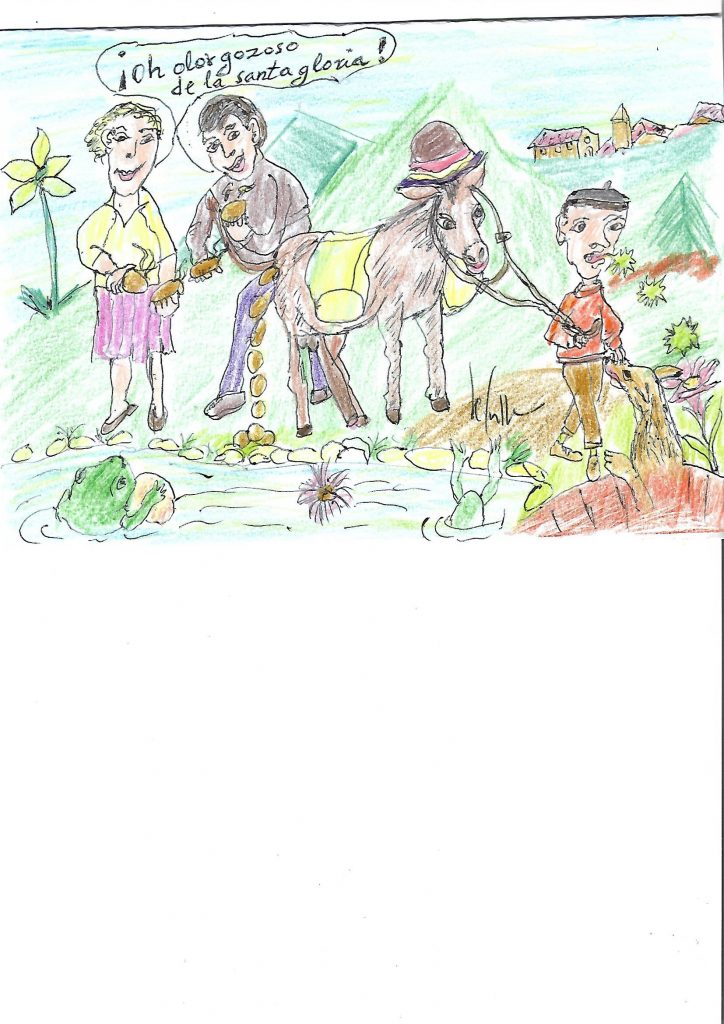

YOUNGSTERS WORSHIPERS OF THE ASS’ DUNG

We were kids and little girls, boys and girls, mischievous and unruly children, “chisgarabís” (pipsqueak), about 40, from four to six years old, the only ones we had in the town of Cañete, in the province of Cuenca, Spain, who, tired of teaching based on stick and tentetieso (tentety), and the reed of the catholic national doctrine, we created a “rock” in which we worshiped the Donkey’s dung, and its Hee-Haw.

The Ass`Hee-Haw was our guide, and not that insipid, insubstantial and false Hee-Haw of the teachers, priests, doctors and mayors, the four important figures of the town, to whom we changed the name Cañete for Chiquiburra.

We liked to tell ourselves that we were mulatto and black children or vice versa, or children of india and zambo or vice versa, because we felt longing for Cuba, since most of our grandparents had been in its war, and they told us good adventures and, rather, bad.

When our heads hurt, our mothers would put slices of grease-smeared paper on our temples as a home remedy for pain.

When we crossed paths with fellow countrymen or women from the town, and they asked us:

-Where are you going little ones (chiquitos)?

We answered them:

-Mr. Mrs; Gentlemen, Ladies, “chiquitos” are the Indians of the southwestern region of Bolivia, and “chirapa” in Peru calls rain with sun.

So much was our love for America discovered by Columbus!

In lofts, corners or hiding places, or at the top and most hidden of a haystack, we looked at our bulba (chirimbolos) and their flageolet(chirimías), objects that we did not understand that they were used for anything other than pissing. Thus, the boys called the girls: “Las ojetes”(The holes); and the girls to the boys: “Los pellejos” (The Skins). Although, for us these two were instruments for touching and kissing.

When we heard a Hee-Haw, we listened attentively, trying to see where it came from and how its master was called in town, to see if he was a good or bad man.

Once seen, we followed the Donkey wherever it was, calling it “ the Holy Father”, and also was called “You”, waiting with enthusiasm and passion, that come out from its arse hole, to which we saw opening and closing like a fig, throwing those half-spherical and warm, steamy dungs, taking them in our hands, and passing them from one to the other, sucking them as in a game of caresses. Someone passed their tongue to see what they tasted like.

Some sparks or particles came to our eyes, blurring our sight.

The owner of the Donkey was called “Uncle Chiriguán”, because he looked like an Indian from the interior of Cochabamba, in Bolivia, and he was also a beekeeper, because he had hives, and they also called him “Uncle Chisquete”, because, when speaking , spit was coming out of his mouth.

This was in the afternoon, when we had already finished school, and our parents did their homework, and they went home confident that they would not have to put up with the kids.

While we passed the dungs from hand to hand, like the small change of money, we sang out of tune:

“Afternoon time

End of work.

Donkey’ Master

Don’t pay your jobs

Based on sticks.

When breaking the day

You beat it

So what it cares your garden

And your ferris wheel

At dawn in the afternoon.

On top of that you hit

It gives us free dungs.

Master, You are lucky

For a donkey’s wages

It does a great job for you

Without paular or maular

Without saying a word

Giving a lesson

To the world of work.

Your Ass is evening

The same as morning

Hours are of it

Although yours are

The orchard and the ferris wheel.

The Ass is your life

Take care of its dungs

That its light shines

All our paths and roads

For us to live

Always in its presence ”.

Sometimes, in summer, the Ass made us very funny, because “Uncle Chisquete” put on a top hat. We looked like a herd of goats and goats behind him.

At night, we took the dungs, which we had brought, to the goshawk that spent the night with the partridge that flew after a not too strong north wind, in the stable of “Uncle Chisquete”. Also, the chochas gallinaceous birds felt love and affection towards dungs, so much that they began to peck them as if they were bean or beans.

-Daniel de Culla