Children of the Long Nights

Of Humans and Hybrids: Drive and Under the Skin

In a way, Drive is a very feminine [and feminist] movie. Feminism is actually more masculine than what masculine is. Feminism is much more interesting.

Nicholas Winding Refn

What does it take to be considered human?

In a film like Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner, the ultimate question of what it takes to be considered human is asked. No answer is provided but according to the film’s ending; to be human is to exist as a citizen of the patriarchal system, understanding what the role expects of the individual; a cis, White, man with a female tagalong who was once an independent hybrid but now a compliant, compassionate ally of the patriarchy.

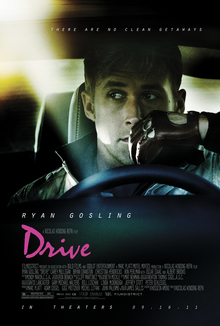

When I first saw Nicholas Winding Refn’s “Drive” a masterpiece of a film about a character on the margins of society, a male whose sole purpose in life is to drive the streets of Los Angeles where he could blend with the surroundings, wearing the definition of cool in the form of a jacket with a scorpion imprint and impersonating the Hollywood antihero who rarely speaks his mind; I realized that feminist films do not necessarily have to be about a female main protagonist. Women in this film come into the male-dominated universe not as candy-wrapped fantasies only for the males to wrap/unwrap, but they exist in their own mini-verses through carefully structured bubbles where their storylines continue unmarred by those of the men’s. Whether the quiet, loving mother Irene or the voluptuous Blanche, the latter appearing for a swift moment to shift the intensity of the film but when she’s gone the audience can’t help but remember her for the rest of their life.

In Jonathan Glazer’s “Under the Skin” a creature taking the form of a female human being drives around looking for susceptible male subjects. In the only moment where the creature suffers an identity crisis of what it takes to be “human”, the creature loses its power, submitting to the patriarchal society which it –supposedly- studies, understanding ultimately what it takes to be a woman and a “dark-skinned” being in a world that is predominantly male and White.

Los Angeles – You can be a Criminal or a Movie Star

I was drawn to “Drive” just as I was drawn to “Heat”; two inherently masculine films that surprisingly broke masculinity with the same tactical focus through which they ascertain glorification. Both films show male characters doomed with their burden of the masculine hero/villain. Lines are blurred between good and bad, men are wrapped in their loneliness and seek solace in the relentlessly coveted city.

In a city like Los Angeles, crime is a glorious, sensational lust. Films that both imply and dissect a society wild with the need to be known or seen either decapitates or assembles the tales of those who thrived and survived on fame in the city of angels. In Michael Mann’s “Heat” and Refn’s “Drive” both films with a single word for the title; masculinity is impaled on the same shrine on which the city is worshipped. “Heat” shows an emotionally-charged finale, worthy of “Titanic”, of two men consumed by loneliness in the merciless city where they get to play their respective roles, even if it forsakes a rather successful friendship that was not and could have been, while “Drive” recounts the tale of the Night prince whose false kingdom of machismo, coolness and the ability to roam an entire city free, no-strings-attached is complicated by the fact that the only thing that means something to him is domesticity; a home with a regular-looking woman and a child. How both films deconstruct masculinity as an ominous presence, able to engulf all that comes in its way; and yet something fragile as to crave the simplistic pleasure of a shelter, says a lot about the ability of their male creators (Mann and Refn) to observe the male-centric world from a realistic, humble lens.

In “Drive”, the driver does not have a name, stylistically even resembling Clint Eastwood’s fetishistic Western depiction of manhood in action. But unlike the series of spaghetti Westerns where Eastwood glorifies in the shining armor of toxic masculinity, Refn’s men eat each other, devouring and devoured by their greed and hunger for power. Even the Driver derives strength not from the anonymity which covers him jacket-to-car, but from the false dream of the domesticated American man, who returns home from war to a simple woman and a child; the perfect depiction of the American dream reconstructed.

Under the Skin – Driving around with a Shell of a Woman

A lot can be associated with Scotland, but to be human is not one of them. To understand the choice of shooting “Under the Skin” there would be to decipher one of the film’s multiple mysteries. Is it about alien invasion? Is it a gender-reversal where Snow White becomes the Huntsman and the Big Bad Wolf is essentially a woman?

Or is “Under the Skin” a gender, sexual and political statement in the face of patriarchy and capitalism? If so, why did the creature break when it tried to examine what it takes to be human? The unnamed creature rebelled against the purpose of driving around in a van, luring male victims into a black abyss where their energy is sucked into a greater alien being.

In “Under the Skin” a trick is played using an icon of modern feminine sexuality such as Scarlett Johansson to play a highly sexual but non-sexualized character. A creature, agender, bound by no form takes the shape and the sexual physicality of a woman to help its camouflage from the land it inhabits. With all the murder and the mayhem, the creature drives around in the van, using the vehicle as a false armor for the fragility of the feminine in patriarchy. Unable to comprehend the icicle thin presence of being a female, the creature abandons the cold, detached driver status to immerse itself in the fragile and flawed world which it tries to take apart one male passerby at a time.

The creature’s predatory attitude is complicated by the fact that when it shelters itself from the emotional mayhem through which gender coexist, it succeeds in being the dominant, alpha presence. Only when it succumbs to exploring what it means to be a female human trapped in a female body, does the creature’s suffering begin. The rape scene at the end, where the creature is both hurt and sexually violated for being a woman, then for being a dark-skinned being, only reveal a glimpse of what it takes to have the upper hand in the human world, and the price to pay when the societal privileged positioning is lost. When the hunter becomes the hunted, the Creatures face demise.

Unnamed Drivers – Masculinity and Femininity from a Lens

In “Under the Skin” and “Drive”; both drivers are unnamed, roaming the roads without much of a purpose for the driving. Unlike “Baby Driver” where the getaway driver uses his position as a purpose to explore his moral compass and his coming-of-age in a criminal, bloody verse where he chooses to escape through constantly listening to music. “Drive” is a film –as Associated Press reporter Christy Lemire states- not about actual driving, the getaway driver is, in fact, a getaway plot twist to trick viewers into believing they are about to watch an action movie, only to discover a layered, character study of male vulnerability in the city of angels. “Under the Skin” uses driving a van as the trap that most men in the real world wield to hunt for their female prey, the faux lure of a sheltered vehicle becoming at times a coffin, or a wheeled metal box to contain the screams and pleas. And yet when the creature decides to rebel against the same power and privilege that it exerts over the human subjects, it becomes human and thus exposed and naked to all things evil that humans act against each other. The Creature is molested and subjected to a horrifying rape attempt because of its disguise as an attractive White female. In the end, The Creature is burned to death because it is revealed as a dark-skinned being, highlighting the fear of the White, cis male of all things dark-skinned and non-conforming to pre-constructed gender and racial politics. A White, lost woman in the dark forest would be raped; a dark-skinned, agender creature might be killed.

Both “Drive” and “Under the Skin” use their leading stars’ power to deconstruct the Hollywood perfect image of beauty and sexuality;

Johansson’s first nude scene is deprived of any sexual metaphors, with her self-reflection a shoutout to the male gaze behind the screens, as if daring them to observe with her a body that would soon be dissembled, and not for the ritualistic catharsis for the man lurking in the darkness of the movie theater, waiting to be enamored by the violence against the woman onscreen, but more of the haplessness that is shared between the audience which beholds a sexual crime taking place; unable to stop it or actively participate in lifting off the injustice that befalls the woman in question.

Ryan Gosling boasts darkness and mystery in “Drive” that has nothing to do with the glamorous Hollywood male stars; the “silent types”. He is vulnerable. He resorts to violence only when his safe “nest” is in harm’s way. Yet, he doesn’t get the girl or get anything at the end. There are no steamy sex scenes or mind-blowing relationships. The Driver is there to suffer, only interlocking paths with the few items that give his sheltered, meaningless life peace. Gosling plays it down to the base with a nuanced performance and an air of undeniable cool. Yet there is nothing extravagant about him or his character.

Both drivers use driving purposelessly. Driving is not an integral element of the plot, nor a plot twist. The drivers here are trapped within false skins; the cool silk jacket with an embroidered scorpion for The Driver, and the lace stockings, mini-skirt and denim jacket for The Creature. Both are garments for false anonymity, which both protect and break their senses of security and gender power when they are undressed.