THE VERTIGO OF IDENTITY

Cindy Sherman

San Francisco Museum of Modern Art

Through October 8

A review by Christopher Bernard

The largest show of this influential photographer’s work to appear in San Francisco opened recently after appearing at the Museum of Modern Art in New York to a complex response by East Coast critics, with a few questioners, if not quite dissidents, providing leavening to the otherwise universal praise. But a complex response never seemed more appropriate than here.Sherman’s work – often charming and witty, beautifully crafted, and slyly probing – is nearly impossible to dislike. And yet, it seems equally impossible, or even desirable, to fully embrace. Which may be the definition of contemporary artistic greatness.

We on the West Coast can now survey the career (up to now) of this popular, fascinating and troubling artist who has shown, with an almost unfailing sureness of touch, how to combine work of great lightness and skill with penetrating, even disturbing, questions, not least of which is “What is this baffling aberration in a seemingly heartless and mindless universe, a human being?”

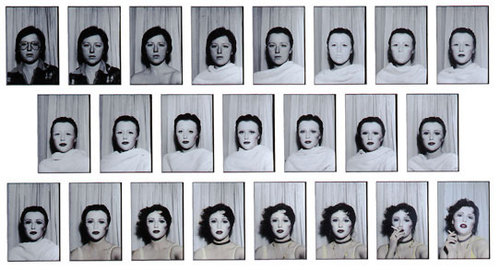

The greater part of Sherman’s work is made up of photographs of herself, usually taken in her studio, in costumes, wigs and makeup, depicting imaginary examples of well-known types, from characters in movies to figures from the history of art to eastern seaboard grandes dames. She works in series, her first, and still best known, being the “Untitled Film Stills” from the late 1970s: black-and-white, deliberately cheap-looking but highly evocative fictional stills from imaginary art, noir and B-movies from the ’50s and ’60s; her latest major series is of big, garishly full-color blow-ups of herself made-up as ageing doyennes of high-society. And in the great majority of the pictures,Sherman, like a great actress, a Meryl Streep of the black box, a Shakespeare of a thousand discarded selves, both appears, and disappears, in an imaginary space that recedes infinitely behind the photograph’s slick surface.

In the early ’80s Sherman created a so-called “centerfold” series, large color photos, based on the centerfolds seen in men’s magazines, of reclining young women, fully clothed but in moments of great emotional vulnerability; examples, not of erotic, but of emotional voyeurism. In these pictures, curiously enough,Shermanis most readily identifiable as herself (as one can see from the occasional candid shots taken of her by other photographers at unguarded moments), with minimal use of costume and makeup, and little more defense than the mask of an expression.

Appearing in the show are also Sherman’s “fairy tale,” “disaster” and “sex pictures” (a peculiarly ugly series, though not surprising: how many artists have ever had a healthy, happy relationship with their own sexuality, candid yet discreet and kind, to themselves, their lovers, and their audience?), a “clown series” (perhaps the only weak images here; creating an artificial identity from an already artificial identity provides the show’s only shruggable moment), grand, booming large-scale photos based on old-master paintings (the so-called “History Portraits”), a “headshot series” of “ordinary” women (and some males) hiding, so to speak, in full view, and a “fashion” series that sends up the very fashions and designers the pictures ostensibly advertise.

And all of these (except for the relatively few disaster and sex pictures) are of the photographer herself in a myriad masks, this woman of a thousand faces who would put Lon Chaney to shame: the opposite of self-portraits, these are pictures of an artist in full flight, apparently, from the self.

But are they?

It’s impossible to discuss Sherman’s photographs without immediately bringing up the issues of “identity” and selfhood, its continuity or lack thereof, its relation to image, its sabotaging by image, its relation to the construction, and deconstruction, of femininity, sexuality, gender roles, and other biosocial categories, its possible nonexistence outside the funhouse of psychosocial illusion, and so forth.

The very variety of her images – and the peculiar vulnerability that often peeks out through the impasto of costume and mask – suggests something else: the hiddenness of the self, the ego absconditus, behind its image; the image as protective covering, as camouflage, as shield, as tool and, when necessary, as weapon.

I had the unpleasant feeling, after looking hard at Sherman’s photographs for two hours while preparing to write this review, that everyone I passed in the streets outside the museum was wearing a costume. The whole world suddenly looked like a Halloween party. Was it even possible to decipher people based on how they appeared? If their image was so constructed, so contrived, how could I possibly get past it to their “real” thoughts, feelings, selves? Even when they spoke, how could I trust what they were saying? Not if course that they would deliberately lie – but then, how could they help it? Are we all just actors playing out a theatrical illusion of who we think we are, want to be, are afraid we might be?

If you leave the show a little shaken in your certainties about yourself and the world around you (I told myself), you’ve probably had the right reaction. Not thatShermanintends to shake us up. She just likes to dress up, according to her interviews, and always has.

The ultimate photograph in this retrospective, the one that lingers more pertinaciously than any other, was one of the disaster series. At first it just looks like a big picture of a strip of dark red soil, soaked with movie blood or red paint. But then, as I looked at it, I saw it resolve into its actual subject: a crushed, skinned unrecognizable face.

Christopher Bernard is a writer, poet, and critic living in San Francisco. He is author of the novel A Spy in the Ruins and co-editor of the webzine Caveat Lector.

Pingback: Synchronized Chaos » Blog Archive » Synchronized Chaos, August 2012: Dedication