“People are trapped in history and history is trapped in them.”

James Baldwin

In this issue, we explore how people are influenced by their times and cultures, and how they learn from and engage with the thoughts of their forebears. Also, we acknowledge the wealth of wisdom and life lessons carried within each person due to the events through which they have lived.

Graciela Noemi Villaverde speaks to the inexorable and irrevocable passage of time.

Amit Shankar Saha writes of then and now, memory and future, remembrance and forgetting, universal human questions. Duane Vorhees’ poetry evokes change, thought, aging, and the creative process.

Stephen Jarrell Williams speaks to memory and the human experience. Eva Lianou Petropolou speaks to artists and authors’ learning from and being inspired by each other throughout the ages. Writer Rizal Tanjung offers up an existential analysis of Eva Petropoulou Lianou’s poetry.

Giorgos Pratzigos interviews Konstantinos Fais on his artwork and advocacy for rediscovering Hercules and ancient Greek virtues. Muxlisa Khaytbayeva records her grandfather Jumaboy Allaberganov’s memories of knowing famed Uzbek author Omonboy Matjonov as a young adult and discusses Matjonov’s contributions to culture. Shukurilloyeva Lazzatoy Shamsodovna relates her scholarly and personal journey to understanding and illuminating Russian writer Alexandr Faynberg’s poetic legacy and its influence on Uzbek culture.

Kuziyeva Shakhrizoda highlights the Uzbek government’s investment in the nation’s youth and the incredible potential of their young adults. Otaboyeva Khushniya outlines how the psychology of early childhood can inform education. Su Yun collects and translates the work of Chinese elementary school students. O’tkirava Sevinch outlines strategies for learning Mandarin Chinese as a second language and for teaching the language in Uzbek schools. Olimboyeva Dilaferuz outlines verb conjugation rules in the Uzbek language.

Mashhura Farhodovna Joraqulova’s short story encourages students from low-income families to persevere with their education. Sevara Kuchkarova outlines strategies to motivate students to complete work at school. Rashidova Shaxrizoda Zarshidovna honors the life and work of a woman who mentored many of the girls at her school. Dilbar Aminova advocates for a balanced approach to screentime in young children’s lives. Shahnoza Ochildiyeva reflects on the value of her journalism education at an Uzbek university. Xo’jamiyorova Gulmira Abdusalomovna highlights the role of emerging and young poets in Uzbekistan’s national destiny.

Duane Vorhees compares the poetry of Phillis Wheatley and Nikki Giovanni as part of a broader comment on changing Black consciousness in the United States.

Cherise Barasch writes with respect for the hardworking people she observes digging into the earth in the heat. Yongbo Ma brings a poetic and scientific perspective to fog. Sayani Mukherjee contemplates peaceful natural scenes in a reverie. Priyanka Neogi compares accepting life’s changes to living through different seasons and times of day. David Sapp reflects on the transcendent experience of seeing a peacock. Dilnoza Islamova looks to nature’s beauty as an invitation to spiritual faith and practice. Maki Starfield sends up elegant reflections on weather and fruits in Thailand as Maja Milojkovic meditates on sunflowers, existence, and perseverance.

Brian Barbeito lets his mind wander to cosmological and existential places while walking near birds by a lake. Orinbayeva Dilfuza rejoices in the beauty of nature at springtime as Dilobar Maxmarejabova shares the emotional significance of tulips in her life. Don Bormon revels in the fun of rain at school. Mark Young renders up more of his fanciful “geographical” maps of Australian regions. Mathematics is a language we use to describe nature, and Timothee Bordenave discusses how his geometric studies inform his artwork. Mesfakus Salahin speaks to drought in Bangladesh in a meditation on accepting life and nature’s cycles.

Bruce Mundhenke urges humanity to turn away from hate towards love and acceptance. Vo Thi Nhu Mai illuminates the beauty and communicative power of the craft of poetry.

Leslie Lisbona sends up a childhood memory of having fun dancing to and figuring out rap lyrics. Marjona Baxtiyorovna Jorayeva celebrates sports and their fandoms and their power to bring enjoyment and bring people together.

Shomurotova Sevinchoy reflects on what it means to be a true friend. Munisa Ro’ziboyeva illuminates her appreciation for her mother’s care. Hamroyeva Shahinabonu Shavkatovna highlights the love and care both fathers and mothers have for their children. Rashidova Muallima offers up her love for her mother. Kamoliddin Hamidullah sends us a tender love poem. Thathanhally B. Shekara expresses his joy in romantic union with his beloved. Vo Thi Nhu Mai looks to wind as a metaphor for gentle connection among people.

Jim Meirose crafts a surreal piece in the language of fairy tales and dreams. Iduoze Abdulhafiz takes a lengthy journey through the subconscious with a wide selection of words. Dr. Maja Sekulic reviews Dr. Jernail S. Anand’s exploration of artificial intelligence, myth, and morality.

Kholmurodova outlines strategies to bring digital access and economic opportunities to the world’s rural women. Rakhimov Rakhmatullo outlines challenges and solutions for logistics technologies. Sa’dia Alisher outlines some benefits, problems, and challenges from modern digital technologies. Gulnora Rakhimjonovna Khomidova explores the educational potential of artificial intelligence.

Dr. Jernail S. Anand relates how, regardless of the tools we use to craft our work, restraint and discipline can serve as a creative force. Dr. Debabrata Maji highlights the power of perseverance and devotion. Azemina Krehic compares the care she has for her poetic works to the process of washing her clothes on a line. Hassan Mistura speaks to the journey of developing a healthy self concept. Surayyo Nosirova reminds us to let go of the illusion of more control than we have and to stay open to change.

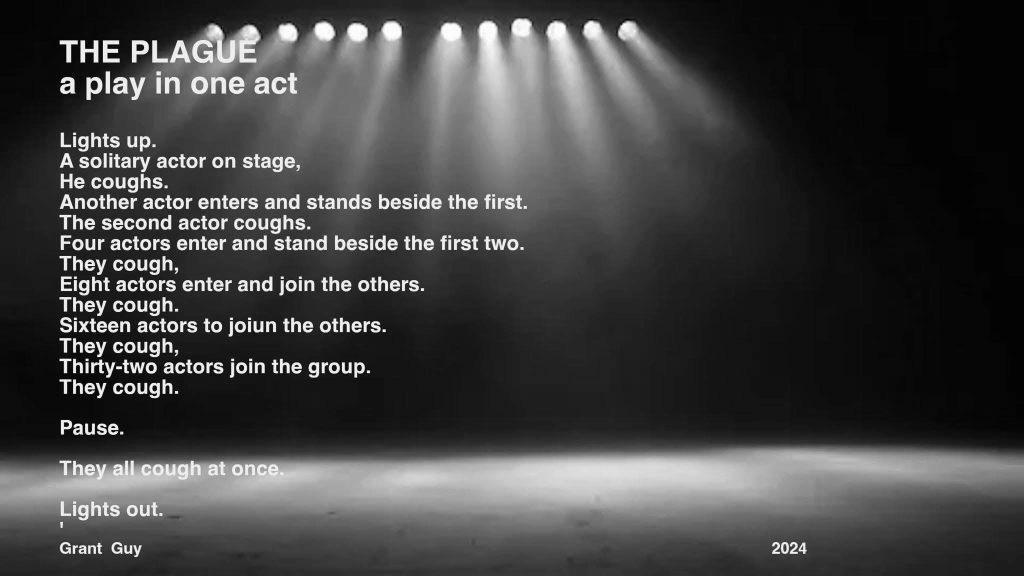

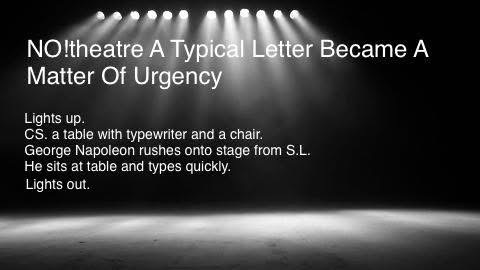

Grant Guy offers up stage directions for absurdist theater, an artistic reaction to periods of rapid social change. Ahmed Miqdad speaks to the absurd persistence of normal life amid wartime. Mykyta Ryzhykh, in a similar vein, evokes the quest for queer love and sensuality among bombs and bullets.

Pat Doyne laments violent immigration enforcement overreach in Los Angeles. Otabayeva Khusniya reveals the deeply humane vision of Erkin Vahidov’s work Rebellion of Souls, a tribute to the memory of Nasrul Islam and other artists who died as a result of unjust persecution. Chimezie Ihekuna shares some of life’s paradoxes and urges nations and groups of people to move away from war as a solution to issues. Mahbub Alam also puts out a call for peace, remembering the many people lost to war. Boboqulova Durdona laments the many civilian deaths in Gaza.

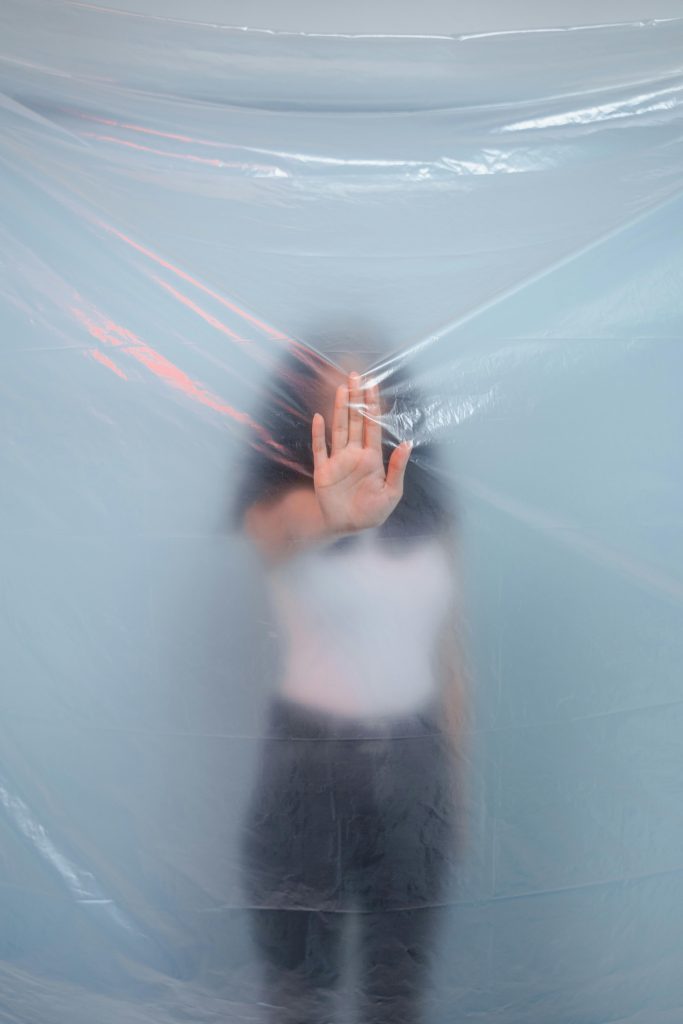

Muslima Olimova reflects on surviving an unhappy marriage and urges families to welcome young brides and for women to carefully consider before marrying. J.J. Campbell speaks to the lingering effects of trauma on people and the tension between hope and disillusionment. Dr. Bindu Madhavi speaks to the inner battles many of us fight as Mirta Liliana Ramirez evokes the pain of loneliness.

Doug Hawley’s short story presents several characters representing a mix of lawful and roguish motives and actions. Taylor Dibbert’s poem lampoons the worldliness of a priest and the devotion it still inspires. Sarvinoz Sobirjonova Abdusharifova depicts the dual nature of humanity: kindness and cruelty.

Kelly Moyer uses vegetable humor to convey and navigate the experience of chronic illness. Alan Catlin frames evocative images with words, plumbing the imagined photos for meaning.

Mark Blickley, a combat veteran who finished education later in life, reflects on what he gained as a person and an artist from popular literature and reminds the “literary” crowd not to so easily dismiss popular writers.