MANY-TONGUED MASTER

EYES

By Jack Foley

Poetry Hotel Press

263 pages

$24.95

A review by Christopher Bernard

[Note: In the opening paragraphs of this review, the interlineated quotations in italics are from “Villanelle” (for Ivan Argüelles), by Jack Foley, from EYES. This is an example of an interlineated text, sometimes called a “foley,” which is discussed later in this review.]

Hour: sunset; fire retreating. Hour

For many readers, EYES will be the most important introduction to the work of one of America’s most consistently interesting contemporary poets. That Jack Foley is not better known, and not yet placed where he clearly belongs, in the upper ranks of modern poets in the

Of thoughtfulness, sweet reverie.

English language, is, I believe, something of a scandal, even a disgrace to the literary establishment that historically has been so notorious for similar follies that “missing genius when it is right under their noses” has become the motto of many “publishers,” “critics,” and “academics.”

Let us talk about the stupidity of publishers. …

Given the futility of much of contemporary American culture, Foley’s work is likely to remain a minority taste until our cultural elites, craven before those great gods, popular

Let us talk of the darkening of thought’s tower

culture, the race to the bottom, and the hypercommercialization of the internet, at some point, out of sheer disgust, relearn self-respect they have forgotten and reassert the values that justify their existence, such as intellectual

Or of the endless reverence for money

courage, confrontation with shibboleths, questioning the authority of the local despot (whether an individual dictator or what has been called the “World Wide Mob”), and the slaying of sacred cattle.

At this hour: sunset; fire retreating …

When that happens, writers and thinkers like Foley may finally gain the place they deserve at the

Let us take the rotting floor!

human mind’s cold, clear heights.

Let us remember the reviews and their duplicity!

There are some benefits, of course, in the present state of things: while we’re waiting, we

Let us talk talk talk about

“happy few” will have him, like a banquet of all but excessively gourmet fare,

the STUPIDITIES

all to ourselves.

of PUBLISHERS!

And as the main course in the banquet, we have this book: a brilliantly shaped selection- Foley’s work from the last several decades, printed in a large, spacious format, with a lovely design by poet, designer and musician Clara Hsu, and graced with a vigorous and munificent introduction by Ivan Argüelles, another of the Bay Area’s poetic masters (and another candidate for wider recognition when “the sleepers finally awake”).

Jack Foley’s work is that of a strenuously active intellectual, which puts him immediately at a disadvantage, of course. America must be only country where the prejudice against intellectuality is so great that even many of the writers run from the aspersion as from a rabid dog.

But Foley’s is a passionate intellectuality, and his work is the expression of a person as deeply humane as he is deeply aware. He is a poet in the ecstatic tradition of Whitman as refracted through the lenses of Pound and Olson and varieties of poststructuralism (where the open-faced smile of the American Emersonian, that happy existentialist, meets the European Nietzschean’s burned grimace), with bits of vaudeville, Cole Porter, George Gershwin, and tap dancing thrown in, all of this mixed and blended in a mind, unique but all-inviting, individual yet multitudinous, a spirit deep as day and as broad as history.

And I say this, and believe it to be no exaggeration, no decorative purple patch, because Foley’s work comes out of the generativity of language itself, a generativity that is, to all practical purposes, and conceivably also to theoretical ones, infinite. He has taken many of the crude prejudices and inane rules of “writing,” the sorts of thing that make writing classes and writers groups a curse and a torment to the spirit (“write what you know, show don’t tell, find your personal voice” and the like) that has turned too much of contemporary “writing” into a game between faux naifs and their shadows, and turned them – rules, naifs and shadows, all – on their heads. As he explains in many a lucid philosophical aside, in both prose and verse (he is not afraid of dumping into the mix of mashup rhetoric, truncated phrase and quotation unchained, a workable abstraction or an unambiguous assertion of his own when needed and helpful), Foley writes not from the center of personality in its more limited manifestations, but from the center of language, which is the archetype of the open system, a generator of meanings that, within the possible frameworks of grammatical rules and systems of phoneme and morpheme, signage, and the like, as well as the hermeneutical practices available to the human species, is essentially without limits. Infinity is thus immediately available to us (as available as it can be to an ultimately finite creature) through language, as it is through mathematics, music and the other arts, and the night sky above us.

At the center of language we also find, curiously enough and mirabile dictu, the great putative value of American culture, though it is a value paid more lip service than real service to. And that value is freedom: the absolute freedom of the mind to fashion its own meaning and meanings out of itself, to fashion its world, to crush the given into eternally fertile and life-giving fragments, annealing and reannealing them, over and over, ever and again, into the wilding and scattering shapes, frottage and fractalage, of the spirit’s – my, your, our – ever-changing fantasies and desires. Foley’s work takes place in the great theater of meaning that is language: an open-ended circus, an epic that has no conclusion, an endless conversation between an infinite number of speakers. In Foley’s work there are only pauses; there is no closure. His work contains, as it opens out to, the unexpressed and the not-yet expressed, literally, as at the “conclusion” of the poem “Fragments.”

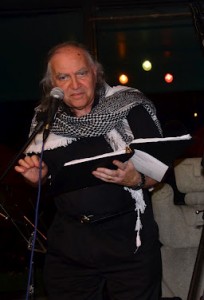

There are few ideas headier than these – indeed, this may be why Foley makes the literary and academic establishment uneasy, strikes them dumb and off-balance; hoping that thereby he will go away, that by ignoring him he will cease to exist. They laugh at him, nervously. His few supporters in the literary establishment are sometimes ridiculed for taking him seriously: “He’s avant-garde, experimental, modernist, postmodernist – an extremist, an outlier, not mainstream, an eccentric, yikes (look at the picture, he’s wearing a keffiyeh!), a t(Errorist?)!” All that crazy modern stuff was supposed to have died with Derrida, after Bush bombed Baghdad and Americans became terrified of being kidnapped in the middle of the night, renditioned to a black site, tortured, disappeared, droned. We’ve gone back to story-telling, flattering, coddling. We want fairytales and porn, modest entertaining little poems, unpretentious, a Harry Potter, an E. L. James, a Billy Collins, a Dan Brown, to keep us bottle-fed, giggly, comfortably napping; the last thing we want is a shaman (how 60s, how quaint!). We don’t want to wake up. We might have to change something. We might have to change everything. We don’t want to hear, in English or German, du muss dein leben ändern. And we don’t want literature to have anything to do with reality.

One had thought that all such weak spirits had perished generations ago – we were beyond such schoolmasterish meatheads. But apparently not – the follies of that time are enjoying a comeback. The 20th century is going to have to be fought all over again – from socialism to modernism, from labor unions to the freedom of the heartsoulspiritmind, from revolt to rebellion, from revolution to liberation.

Foley’s work is a reminder of what is at stake.

Enough of ranting, deserved, alas, as it may be; now to a little description. But how does one describe the unique?

At the center of Foley’s literary project (to use an old, but always useful, existentialist term) are a few simple discoveries: that “literature is made up of letters” and that language “speaks us” as much as we speak it, which discoveries (along with the modern notion of the mind’s, and therefore the self’s, unconscious and multifarious drives, in which the ego is less like a crystallized monument to its own ambitions (often our preferred self-image) and more like an arena of energies in constant interaction, frozen only, achieved like a work of art, a symphony, a novel, a poem, at its conclusion) made the multi-voiced poem not only possible but, in a sense, inevitable.

This kind of poem, as practiced by Foley, often incorporates other texts (the poet sometimes rewriting them, bending then, shifting them, shaking them, making them other, making them “wrong”; chopping them up, sometimes rough, sometimes fine, like a chef cooking his dish out of meat and meanings; Foley, the echt modernist, is in this the echt postmodernist as well, just as in his casting about in analog hyperlinks he discovered the internet of culture before the clever fellows of ARPAnet ever dreamed of the internet of technology) to create not so much collages as (as he calls them) “collisions” of texts, from which meanings are presented, produced, invented, hinted at, questioned, splintered, shaved away, blown up, shattered, destroyed, renewed, and then spun through the whole process again and again, in a perpetuum mobile of created meaning, which is the heart of language in its absolute freedom, which is human freedom itself, fantasy, dream, imagination: our only way out of the inferno of reality, our Paradise rose holding universal love in its infinitely opening blossom. It is like an enactment of Maurice Blanchot’s “Infinite Conversation,” without the gray continental flavoring, its flirtation with nihilism and despair; on the contrary, it is exuberantly cheerful (“energy is eternal delight”) and alive.

The immediate engine of this process in Foley’s writing is the question, sharp, and often humorous too, in its Socratic sense of perpetual undercutting of received understanding. In Foley, this does not lead by way of reductive approximations to a unitary meaning, as so often seems to happen in Plato’s dialogues (though often less so than is commonly supposed – many of Socrates’ questions are ultimately left open and not definitively answered; even Socrates seems to be aware that he had opened a Pandora’s box indeed; that all answers are provisional and only questioning is eternal – maybe the world began with a play of questions: “Quark asked: Why?—

Why not? said Higgs” And off we were to the races) and the wretched forced march of western philosophy that followed.

Foley’s way of questioning, like Socrates’ and like the German philosopher Martin Heidegger’s, open out into a plethora of possible understandings, undermining the received “wisdom,” the prejudices, the pre-judgments, that many of us bring to common concepts, and all of us to some of them. (What is a “personal voice”? What is “personal”? Isn’t it possible that nothing is personal, nothing individual, (“I am not an ‘individual,’” as Foley says at one point. “I am as divided as can be”), that we are all just made up of the scraps of other people, and those people are made up of the scraps of other people, and so on, ad infinitum, ad nauseam, et ad absurdum, and that there is no ultimate origin? And “what do you mean by ‘voices’?” anyway)

In this sense, Foley is a philosophical poet par excellence, though he practices his philosophy outside the bankrupt discursive practices of western philosophy (philosophy is of course not “dead,” pace Heidegger, Adorno, Derrida, Badiou, Agamben e tutti quanti: philosophy will die on the day that people stop asking questions: whenever you ask a question, you are “doing philosophy”; whenever you ask it insistently, so much so that it becomes a matter of life and death – in this sense Christ, Moses and Socrates are one (the defining Judaic question is the vertiginous set of questions “What is the law that I must follow? And why?”; the defining Christian question is “Why hast thou forsaken me?” and we are still waiting for an answer) – then you are “doing western philosophy”: it is the west that made a fetish of the question; elsewhere, before and since, people who ask questions too persistently are killed) – he seems to have been impressed, and perhaps influenced, by Heidegger’s ideas about language and being, his approach to ultimate questions that are never, finally, answered, and then has taken those ideas to the logical next step. And (as he has said in other situations) he has been influenced by the ideas of Paul de Man on deconstruction, though not to undermine language; on the contrary, to liberate it in literature, and by so doing, purify it, reminding us of what we have been doing all along: that language is our responsibility, a tool, an instrument. And that its innocence is our obligation.

Foley’s multi-voiced poems led, naturally, to his “choral” poems, which are performed by two or more voices simultaneously: some of his choral poems incorporate work by other writers (Foley also practices a kind of interlinear poem, called a “foley,” in which he adds his own lines between the lines of another writer’s work, turning the usually monologic lyric into a dialogue; a poem becomes a heteroglossia; all literature becomes overtly what has always secretly been: a wealth of talmudic marginalia).

For many lovers of poetry, especially those who live in the San Francisco Bay Area, which is fortunate to enjoy the poet’s bracing, sane and warmly human presence, the choral poems are Foley’s best known work. In a way, that is something of a misfortune, because these readings can give Foley’s work a superficial resemblance to the free-associational rhodomontades of the Beats and their followers, and what one sometimes misses, in the pleasant but sometimes half-baked theatrical experience of the contemporary poetry reading (no lighting, no music, no costumes, no rehearsals), is a sense of the extraordinary care with which these texts have been constructed; this comes across on the written page far more clearly than in the comparative limitations of a staged reading. One misses the visual element too, the placing of words and phrases, “marks,” like skillfully made drawings, woodcuts, engravings, on the page. The ideal experience of these poems might well be to simultaneously follow them on the page, like a musical score, while hearing them being performed.

In EYES we can most easily enjoy the expansive exhilaration of Jack Foley’s literally inimitable work, where no two poems are alike, where in some cases they can never even end, where each work is crafted to a unique shape, where voice becomes voices (“What are ‘voices,’ anyway?”)—a gift to the culture, the country, the time, however long it takes us to catch up to it:

we are not—

those masters of language

summon wor(l)ds

which

resonate

resound

so that experience is

alive with random fragments seeking others—

fragments summoning

not unity but constant interaction

—“Fragments”

I see this review has often wandered from its subject, and for that I apologize. But it is just one example of the stimulating power of Jack Foley’s work: it does not let you settle down even on itself for very long – it opens the mind to the mind’s many worlds, and encourages you to pursue thoughts, ideas, words, universes, out of the received sanctities, the limitations and limits, the presumed security and safety, of literature – out, into the open, as far as thought dares to go. It’s not the only way to write, of course, but it is certainly a valuable and hopeful one. It is, above all, liberating.

By the way, did I mention that Jack has a sense of humor, sometimes quite wicked? You don’t believe me? Read “The Marx Brothers Run the Country” and weep with laughter, my dears. (Our masters have been reading Jack Foley even if our critics haven’t.)

____

Christopher Bernard is a poet, novelist, essayist, playwright, photographer and filmmaker living in San Francisco. He is author of the novel A Spy in the Ruins and the recent collection, The Rose Shipwreck: Poems and Photographs. He is also co-editor of the webzine Caveat Lector.

Pingback: Synchronized Chaos » Blog Archive » Synchronized Chaos December 2013: Defining and Asserting Identity

Pingback: Synchronized Chaos August 2016: Storms of Change | Synchronized Chaos