The Phoenix Rises at the University of Chicago

by Jeff Rasley

John D. Rockefeller gave the money and Marshall Field gave the land to create the University of Chicago in 1890. Rockefeller considered the U of C “the best investment I ever made.” Chicago has produced more college presidents than any other American university. Eighty-five Nobel winners have served on the faculty or studied at the University of Chicago. Rockefeller certainly got his money’s worth.

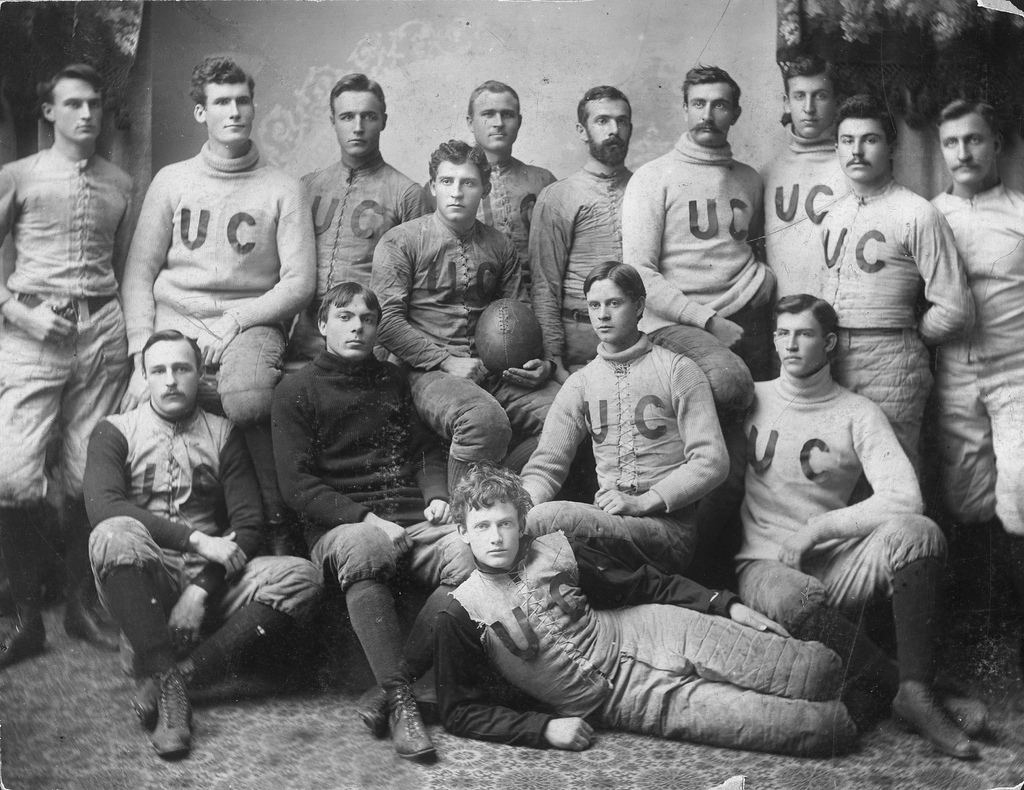

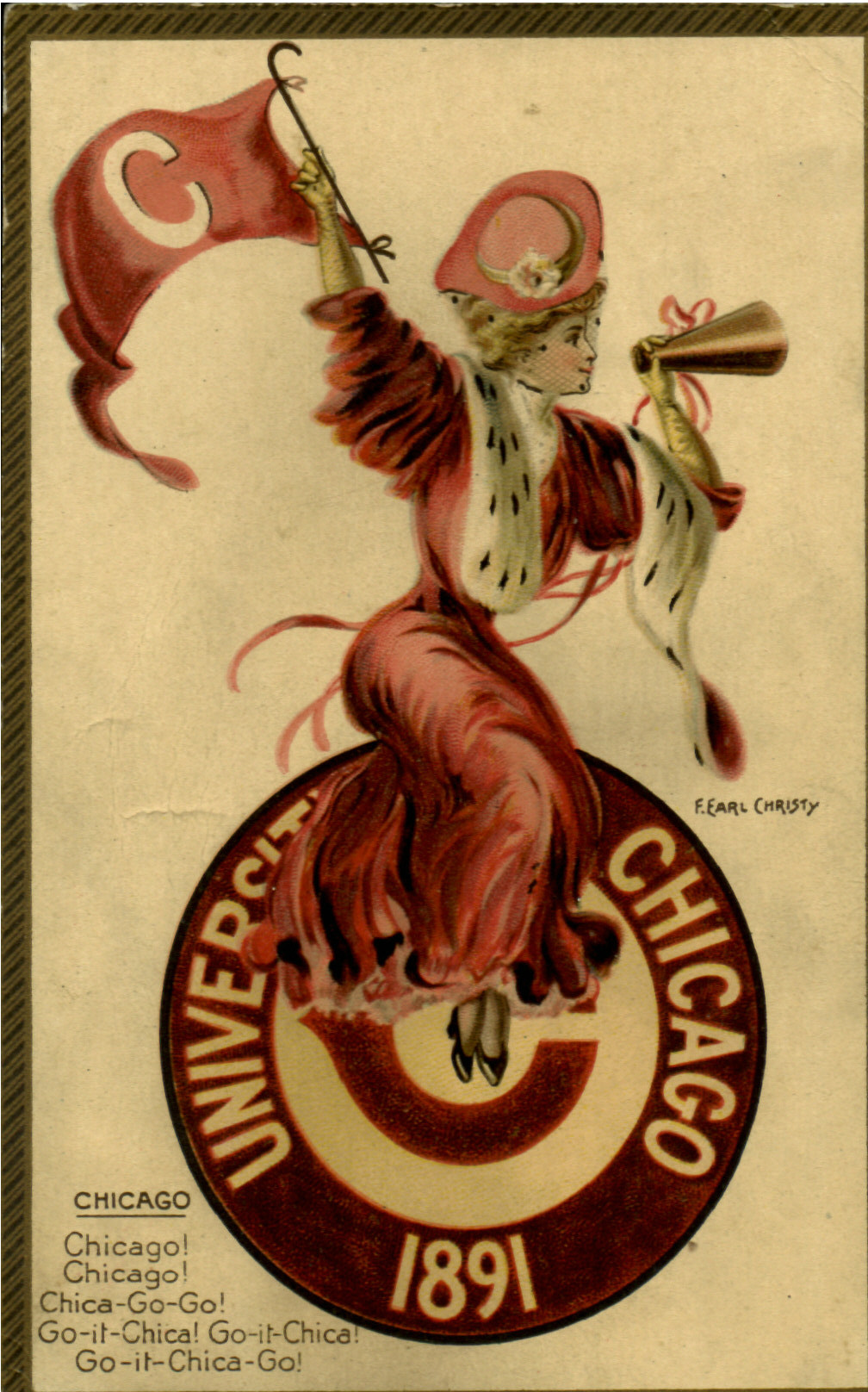

In the first third of the Twentieth Century, however, U of C was admired more for the prowess of its football teams than its academics. Amos Alonzo Stagg’s Monsters of the Midway ruled the Big Ten from the 1890s into the 1930s. He won more games than any other college football coach until Bear Bryant of Alabama surpassed Stagg’s record of 314 wins in 1982.

Robert Maynard Hutchins became president of the University of Chicago in 1929 at the age of thirty. Hutchins’s vision for the University was that students should be completely engaged in “the life of the mind”. He was no fan of football or of Stagg. “When I feel the urge to exercise, I lie down and wait for it to pass.” Hutchins was not an athlete. He wanted out of the Big Ten and to rid the University of football.

The 1939 season provided the leverage Hutchins needed. In 1939 the Maroons suffered defeats by Harvard and Ohio State 61-0 and an 85-0 loss to Michigan. It was utter humiliation! Bad enough to be slaughtered by Ohio State and Michigan, but beaten by Harvard 61-0! Even the most devoted fans recognized that the Monsters of the Midway had devolved into the lab mice of the Midway.

What to do? Dropping down to play the cow colleges of lesser conferences was unacceptable to the proud institution. Hutchins argued that killing off football was the logical solution. When the faculty approved Hutchins’s proposal to terminate football with extreme prejudice, Hutchins responded, “Football has the same relation to education that bullfighting has to agriculture.”

Chicago dropped football and left the Big Ten Conference after the 1939 season. “In many colleges, it is possible for a boy to win twelve letters without learning how to write one,” President Hutchins opined in The Saturday Evening Post. He labeled college football an “infernal nuisance”. He thought he had rid the University of Chicago of it forever. But thirty years later in 1969 the infernal nuisance was back. Sort of.

The referee blew his whistle calling the captains of the teams to the center of the field for the coin flip. Students with cardboard signs had been hanging around the entrance gate. When the whistle blew, they rushed through the gate onto the field. The protesters milled around the flummoxed referee. They raised cardboard signs of “Ban the Ball” and shouted, “Ban fascist imperialist football!”

Dean of Students Warren Wick strode onto the field to confront the protesters. He informed them that they would be subject to disciplinary action for disrupting a sanctioned University event if they did not immediately leave the field. A leader of the demonstrators argued with the Dean about whether a football game qualified as “an event”. The argument became more heated as issues of judicial procedure and due process were introduced. The disputants moved toward the sidelines waggling their fingers at each other. The fifty student protesters followed shaking their signs and pumping their fists in the air. A slim woman with long straight-blond hair and a black beret shouted, “Football is a manifestation of the rapacious male-dominant culture! First it’s oppression, next subjugation, then rape!” A bearded young man in a jeans jacket shook his fist and yelled, “Violence solves nothing!”

Walter Hass began his campaign to resurrect football at the University of Chicago in 1956. His efforts finally came to fruition in the fall of 1969 when, although delayed by fifteen minutes, the Maroons beat Marquette University 14-0. The first game played on Stagg Field in 30 years ended with fans tearing down the goalposts.

Athletic teams of the University of Chicago are called The Maroons, but the mascot is the Phoenix Bird. In Egyptian and Greek mythology, the Phoenix dies a fiery death but arises from its own ashes to live again. Wally Hass enjoyed reminding tweedy detractors among the U of C faculty that resurrection of varsity football must have been foreseen by the legendary Stagg, since it was the great coach who had chosen the Phoenix as the mascot of the Maroons.

Coach Hass’s joy at the propitious beginning of the resurrected Maroons did not have legs. From that first season in 1969 until his retirement in 1975, the Maroons compiled a heartbreaking record of nine wins and forty losses. Sex, drugs, rock ‘n roll, the Draft Lottery, the Anti-War Movement, and student rebellion on college campuses in 1969 — resurrecting football the same year four hundred students occupied the University of Chicago Administration Building was swimming against the cultural tide of the times.

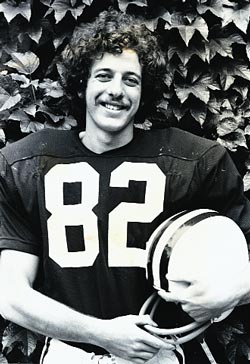

It was during the resurrection era, or Hass years of Chicago Football as Athletic Department historians call them, that I joined the team. I’d grown up imagining the football games of the Stagg era during the Roaring Twenties. My maternal grandfather, Joe Stutz, played professional football and owned a team, the Goshen Greys. Grandpa Joe regaled my brother and me with tales of his gridiron glory, when fans wore raccoon coats and waved banners for the home team.

Times change. I was a star player on the middle school team in our small town in northern Indiana, but quit football, the sport I loved best, after high school tryouts. It was the late 60s. The political and cultural consciousness of the anti-war and civil rights movements had even reached small towns in Indiana. When an assistant coach lined the players up and walked down the line punching each of us in the gut my love affair ended. I couldn’t tolerate what my fifteen-year-old brain interpreted as the coaching staff’s fascistic and brutal attitude. I turned in my gear to the team manager and figured I’d never play football again.

Playing for Coach Wally Hass was different. He was an idealist and loved using the term “scholar-athlete” when talking about sports at the University of Chicago. He rarely raised his voice in anger, despite the teeth-grindingly poor execution of his teams. We knew he was on the edge when he’d raise his clipboard as if to hurl it to the ground, but he’d restrain himself, sigh, and call the next play.

Before I donned a helmet I received assurance from Coach Hass that players would not be punished for missing practices for academic reasons. I would not have considered playing if the normal college football regimen had been required. I was delighted to have the chance to play football again, but not six days every week. Students at the academically rigorous U of C typically spend four or more hours per day studying outside of class time, and I had to work part-time to help cover expenses. I purposely scheduled a class to conflict with practice on Tuesdays and Thursdays. While my teammates sweated and grunted through tackling and blocking drills, I practiced the more sublime exercise of translating Plato’s Symposium from the Attic Greek.

Many of my teammates shared my ambivalence toward practicing football. Rarely did twenty-two members of the team show up for practice, so team scrimmages were jerry-rigged affairs with ghost players, like neighborhood sandlot games. Each player had his own motives for joining the team. Some were quite bizarre. One of our defensive ends told me during tackling drills that football was good therapy for his Oedipal complex. Hitting other players on the field was a way to sublimate the desire to kill his father.

Johnson’s lies about Viet Nam and Nixon’s lies about Watergate left many of us cynical about authority and the use of organized violence. Yet, Coach Hass’s dream to resurrect the tradition of football weirdly managed to inspire my teammates. We had long hair, mustaches, and beards. We were not your typical jock straps.

Paul Mankowski, classics major and host of The Baroque Masters radio show, joined the team because he lost a bet. But he stuck it out and was rewarded by breaking his leg in the last game he played. Paul later became a Jesuit priest and ministered in the Calcutta slums. Tony Miksanek was five feet six, 135-pounds. He was our second-string nose tackle. Coach Hass reasoned that Tony could slip between the legs of offensive linemen, or, they might trip over him. Hans Van Buitenen was a Sanskrit scholar. Hans was six foot three and weighed 295 pounds, but he was such a gentle soul that Coach Hass lost hair trying to motivate Hans to hit an opponent. Our one truly outstanding player was Nick Arnold, the district-leading ground-gainer his senior year of high school and MVP of our team his freshman year. After one season with the Maroons Nick quit football and moved to France.

Jay Berwanger, a living legend from the Stagg era and the very first Heisman Trophy winner, was in the stands when we lost the 1974 homecoming game to Oberlin 69 to 0. Their kicker missed the final point-after thus denying the visitors a perfect 70. I was credited with the longest gain for the Maroons. I fell on the ball during a kickoff return and earned a 15-yard penalty when an Oberlin player speared me while I was down.

The resurrected Maroons, despite our failures on the field, or because of them, were darlings of the media. Sort of. Second City developed a skit, “Football Comes to the University of Chicago”. It included a bit about a squeamish quarterback reluctant to place his hands under the center’s hindquarters to receive an oblong spheroid. “Coach Hass, doing his best not to lose patience, reminds his philosophically inclined Maroons that ‘we have a left guard and a right guard — no Kierkegaard here, gentlemen.’”

During the 1974 season, in which we lost every game, People Magazine called us “the worst team in college ball”. The sleight wasn’t even limited to football. People’s publisher offered to fly the team out to Los Angeles to play Cal Tech in the Rose Bowl. Cal Tech’s players claimed their average IQ was a number greater than their weight. Coach Hass refused on the grounds that it would do irreparable psychological harm to his players to participate in “The Toilet Bowl”, as People planned to call the game. Hass didn’t relent even after the magazine offered to change the name to “The Brain Bowl”.

Despite, or because of, the team’s lackluster performance on the field, a unique culture developed around Maroons Football. In 1971 a refrigerator was crowned homecoming queen. A line of utility vehicles from the physical plant led the homecoming parade for several years. An anonymous steam calliope player occasionally appeared and piped away during games. The Kazoo Marching Band with “the largest kazoo in the Western world”, nicknamed Big Ed after U. of C. President Edward Levi, was wheeled onto the field at halftime. The Lower Brass Conspiracy, eight college musicians pretending to be a pep band, led a mass of students in Brownian Motion, where everyone ran around chaotically thereby representing the random movement of subatomic particles.

One cheer all our fans knew and yelled out on the rare occasion there was a play to cheer about:

Themistocles, Thucydides, the Peloponnesian War,

X-squared, Y-squared, H2SO4,

What for, who for, who ya gonna yell for?

Chicago! Chicago! Chicago!”

Playing during the Resurrection Era was a bittersweet experience. It was heroic in a way. James Redfield, my Greek and Philosophy of Discourse professor, likened the team to Hector preparing to battle Achilles. We faced bigger, stronger, better prepared opponents each week, and lost week after week. Yet, we took the field come game time every Saturday.

Times have changed. The Maroons routinely compete for the conference title in the University Athletic Association, which they have won four times. In 2010 the team won every conference game. I attended practice a couple years ago. There were at least 60 players running crisply and efficiently through drills, letting out bellows of effort and roars of team spirit. The uniforms were similar to ours of forty years ago, but the players looked different — not just bigger and faster, but with short hair — they were clean-cut and listened respectfully to their coaches.

Hundreds of enthusiastic fans pack the stands of Stagg Field for Twenty First Century Chicago Football. At the end of each game the players gather midfield and sing:

Wave the flag of old Chicago,

Maroon the color grand.

Ever shall her team be victors

Known throughout the land.

With the grand old man to lead them,

Without a peer they’ll stand.

Wave again the dear old banner,

For they’re heroes ev’ry man.

Just like the glory days of Stagg and the Big Ten.

My teammates wouldn’t have known the words to the song and would have considered such a sentimental display very uncool. Now, it’s beautiful.

When these players gather for their homecomings forty years from now, they’ll relive winning conference championships. The memories of my teammates are quite different, but they’re all we’ve got. The Athletic Department’s record books for the Hass era teams disappeared after Wally’s retirement.

So, our recollections will have to suffice. And the best one is that we won the very last game Wally Hass coached, and I played, at the end of the 1975 season, after three years without a victory. Once again, Chicago beat Marquette. The fans tore down a goalpost.

This is a modified excerpt from Jeff Rasley’s ebook Monsters of the Midway; Love and Redemption in College Football, which is available on Amazon. Jeff is a previous contributor to Synchronized Chaos with stories about Wounded Knee and his foundation in Nepal, the Basa Village Foundation. His website is www.jeffreyrasley.com

Just great writing….

Thank you, Halsey, glad you enjoyed the piece.

Nice work.