It seemed to be hot the night Dr. King was assassinated. In April of 1968, I was eleven years old and I watched on the television that he had been shot. My foster father’s apartment was across the alley from my foster mother’s apartment. The alley was cool, not hot this time of the year. As I walked through the alley, someone said, “King is dead!” I yelled back something to the effect “yea!” I did not know that what was to follow that night would change not only the world, but my corner of the world. “Niggers not going to stand for this!” my foster mother cried out. She was a lady in her late sixties maybe early seventies at the time. A chill ran down my body. I was frozen in time. It was as if the world were going to end.

Living in the nation’s capital for eleven years, I had witnessed so much violence: shootings, people who had their throats cut and survived. My foster sister’s husband Richard was one of those who had survived having his throat cut. I could see the scar around his neck. I had no idea as to the reason, but it was clear to my young eyes the mark that the straight razor left. These weren’t the only memories I had of living in the streets of Chocolate City, as the black inhabitants called it. The only white faces in my neighborhood were owners of the corner stores and the priest at Holy Redeemer Catholic Church. The blacks had no need for whites except for those who owned the stores and hired neighborhood residents. The majority of the neighborhood shopping was on Seventh Street in Washington: the day-old dollar bread store, the farmer’s market, and clothing stores along a mile radius of Rhode Island Avenue, extending down towards P street and beyond.

My life was going to JFK Playground on P street across from Seventh Street, Northwest Washington. A giant slide curled around and down from the top of the hill to the dirt bottom, there was a tank we could climb on, and the biggest toy for me was a gutted fighter-jet plane which I would climb into and pretend I was a fighter pilot. My foster father loved to watch television shows such as Combat and Twelve O’clock High along with Rifleman and a variety of other shows. It was the war shows that I enjoyed watching and loved acting out on the tank and fighter jet. Across the street from the playground would be the book-mobile on Mondays, where I would go get books with pictures in them. Unable to read, I would lay them out on the floor and look at the pictures in my foster father’s apartment.

It all seemed so innocent before that night that Dr. King was murdered. I mean, I had been robbed and had my money taken by older kids by age ten. I had worked around prostitutes and walked in the alley with broken glass bottles and rocks we threw at one another for fun. I had witnessed car accidents leaving blood on the streets and then there was that kid they found in the abandoned apartment across the alley from my foster father’s apartment the summer before the riots of 68. But the following weeks were a blazing inferno that raged without mercy.

It started, as I recall, with a mob of people chanting in the streets “Burn, baby, burn!” I hid in my foster father’s apartment and I don’t recall if he were home. It all seemed so unreal that first night of the riots. The crowd was chanting words out of fear that I don’t remember. I didn’t want to remember. I had been afraid of black people ever since I could remember. The beatings at home and the beatings in the streets and the violence always there in the neighborhood on the weekends. However, this was different because everyone seemed enraged. The crowd moved within the neighborhood, setting cars on fire and shouting “Burn, motherfucker burn!” They set cars on fire and shouted, “If you don’t want your house burned down, you’d better put “Soul-brother” on your door!” My foster father used shoe-polish on a sheet of notebook paper and wrote “Soul-brother,” and posted it on the green door of the apartment. This is the only time I remember him being in the apartment with me.

After a day or two, I’m not clear about the sequence of events, but I remember the burning down of my neighborhood and the Seventh Street corridor. I was out there with the looters, police, National Guard while the helicopters circled overhead. The mobs had come together after burning down the neighborhood stores. As I walked through the rubble and the broken glass, I smelled smoke; it filled my lungs and burned my eyes. I was so afraid of life, of people, of dying in the fires. I don’t remember any firetrucks coming as my neighborhood burned to the ground.

The walk to Seventh Street was long as the smoke circled around and up. The rubble smoked, and the smell of plastic and wood lasted for months and months afterwards. Cookie and some of us kids went to Seventh Street during the riots. As we approached there were people carrying TVs and stereo equipment, arms full of clothes, any and all things that one could want. “Go get you some; it’s free!” I heard. Walking around as bricks flew into windows and the glass shattered and the ground shook as guards stood with their gear prepared for war. The police were there as well as so many military vehicles.

Everything smelled of smoke. It wasn’t just the smell. It was the sight that my neighborhood was destroyed. Nothing existed that I knew; was all gone. Nothing was of use or value after the fire storm in my world. The canister landed and exploded, and the crowd yelled. “Tear gas, tear gas!” Cookie said, “Hold your breath.” Trying to run holding your breath is difficult as my eyes were burning, and the tear gas soaked my clothes. I remember turning the corner and running.

The water was cold as my foster mother washed me. My clothes were useless, and it all added to the experience that I was in a war-zone. The world seemed to have stopped. There wasn’t any school, nor was there anything to eat but canned goods, and the water was cold to bathe in. It all began to just fade. Each visit outside was a reminder that my world was destroyed. There was a curfew and the military-jeeps with the radio antennas with mounted guns raced through the streets. It was extremely dark since there was no power. Nothing seemed to be real; nothing felt alive, and I was just stuck in a place and time that had been destroyed. This feeling of those images came to me in the night as I slept and peed the bed. I don’t remember the following months in my life. The world had a glaze to it. JFK playground melted in the storm of fire. There had been fires in the neighborhood prior to the riots, which always frightened me, but this was different. I was numb.

The pews in church were a caramel color; the statue of Mary, the Mother of Jesus, stood guard, and the stations of the cross had a different meaning for me. The candles burned and there was no smell of smoke in the air. It smelled fresh with the smoke from the burning frankincense. It was different from riot smoke. I stared at the murals above the altar of angels with their wings opened as if they wanted to hold me. I would sit there for what seemed like forever. It was the only place that made sense to me and even then, I knew what was beyond the doors. Nothing mattered. No signs of life; it was if everyone were a shell. The neighborhood was a shell and the destroyed buildings were a reminder of what had happened that April of ‘68. I was so empty inside waiting for something, for someone, to make it all go away; however, that was not the case. The killing of Dr. King brought so much destruction. There were 13 people killed, according to one source and 900 businesses destroyed. I find it hard to believe that only 13 people died in D.C. During that period, more blacks died in the city on the regular weekends full of drinking and violence.

The memory of the riots did not fade as I sat in the church alone. It was all a bad dream that never went away for me. No one talked about what had happened that week, those months, and years later. No one said, “These people have been through a war and they are suffering from Post Traumatic Stress.” No! there was no talk about all that was lost. It wasn’t just the riots. It was a generation of young people that had been affected by having the military standing there with those rifles, with machine guns mounted on jeeps, helicopters roaming in the airspace. I often wondered what had happened, and like all the other difficulties that has been presented to my race (blacks), I wonder what we could have done if the city had not been destroyed.

I think of what my life would have been if I had not been through the war of ‘68. As the Vietnam War raged, we back here in the cities were fighting for our freedom. It was a collective voicing that we had been denied a chance for life. I often remember not only the riots of “68, but the city and the harshness of inner-city life. The riots were just a result of injustice, and a plea for fairness, dignity, and a chance for a meaningful life. While white America watched my city and many other cities burning, no one came to help rebuild a country that had been torn apart by racial injustice.

It was a long night on April 4, 1968. It was the night that a part of me died when my city died. My city, my neighborhood, and my home. It was what I knew; It was my place even with all the prior violence and threats to my life. It was a place where I had learned to be safe, until the riots. Forty-nine years ago, this week, a part of me died when the army marched through my neighborhood with machine-guns mounted on jeeps. This wasn’t the TV show Combat, this was my home.

An aerial view showing clouds of smoke rising from burning buildings in northeast Washington, D.C., on April 5, 1968. The fires resulted from rioting and demonstrations after the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr.

https://www.theatlantic.com/photo/2018/04/the-riots-that-followed-the-assassination-of-martin-luther-king-jr/557159/

President Johnson called federal troops into the nation’s capital to restore peace after a day of arson, looting, and violence on April 5, 1968. Here, a trooper stands guard in the street as another (left) patrols a completely demolished building.

https://www.theatlantic.com/photo/2018/04/the-riots-that-followed-the-assassination-of-martin-luther-king-jr/557159/

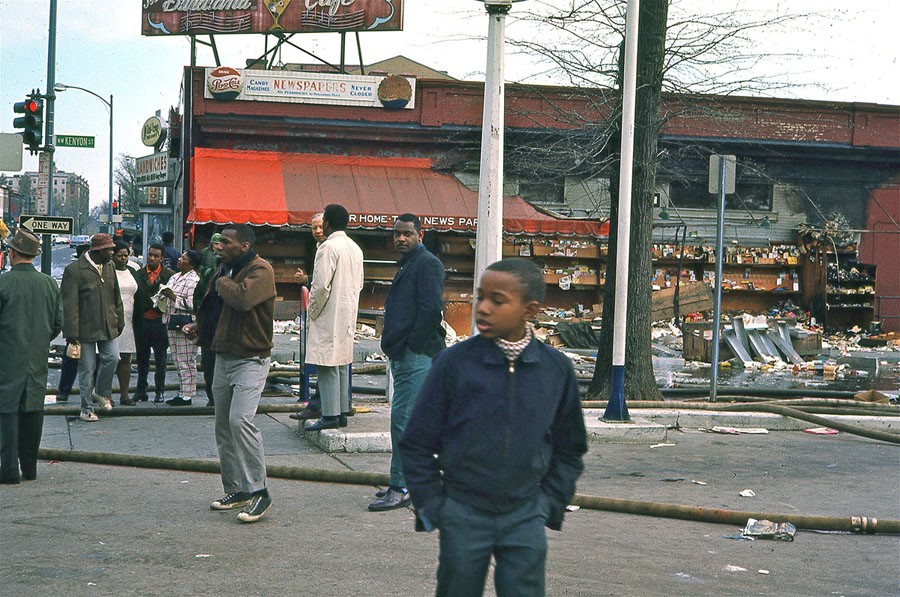

A soldier and civilians walk near a destroyed newsstand at 14th and Kenyon Streets in northwest Washington, D.C., on April 6, 1968, following rioting after the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr.

https://www.theatlantic.com/photo/2018/04/the-riots-that-followed-the-assassination-of-martin-luther-king-jr/557159/

People stand near a destroyed and burned-out building on 14th Street and Kenyon Street in northwest Washington on April 6, 1968.

National guard troops stand at the intersection of 7th and K Streets in northwest Washington, D.C., on April 6, 1968.

https://www.theatlantic.com/photo/2018/04/the-riots-that-followed-the-assassination-of-martin-luther-king-jr/557159/

A pedestrian is waved away from an area by a gas-masked national guard soldier guarding an area near 7th and K Streets in northwest Washington, D.C., as rioting continued in the city on April 6, 1968.

Remember that time Uncle Sam gave D.C. kids a tank and jet airplanes to play on?

Taylor, Alan. “The Riots That Followed the Assassination of Martin Luther King Jr.” The Atlantic, 12 Apr. 2018, www.theatlantic.com/photo/2018/04/t+e-riots-that-followed-the-assassination-of-martin-luther-king-jr/557159/.