The Father’s Instinct

Note: this neuroscience column is published monthly in SynchChaos.com magazine

| topic | nurturing |

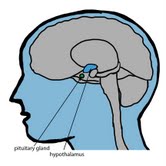

| region | pituitary gland, hypothalamus |

| chemicals | oxytocin, prolactin, testosterone, vasopressin |

tiny bundles

white yellow orange red

chicks being fed

The newborn pigeon chicks are being fed by their grey and black father. A few weeks ago, they were two tiny white eggs.

The newborn pigeon chicks are being fed by their grey and black father. A few weeks ago, they were two tiny white eggs.

“They hatched!” I send a text message to my boyfriend. We take delight in this incubation-hatching-fledgling drama taking place just outside our apartment. Despite advice on the internet that pigeon birth cycle can turn into a nuisance, our curiosity wins and we allow the budding pigeon family to stay in the twigs nest they have built near our fire-escape stairs.

After the hatching, the father sits on the chicks to protect them as they grow. Sometime I see him feeding them but mostly he is a stoic silent dad, acting under the influence of his instincts. At night, the mother takes over the job of nurturing. Both parents’ brains are releasing the prolactin hormone which is secreted by the pituitary gland via instructions from the hypothalamus. In the case of birds, this chemical is released when the bird sits on an egg. Prolactin causes the secretion of milk in both pigeon parents thus the father is able to feed the chicks during the daytime and the mother at night. There is a decrease in the father’s testosterone level at this time also which is why he is able to shift from copulation to nurturing.

In humans, women start to secrete prolactin as the child is about to be born and continue to secrete it during the breast-feeding phase. Males, however, do not release prolactin nor do they show a reduction in testosterone production when the female is involved in child care. That is, unlike bird fathers, the human male does not decrease his sex-drive while his wife is rearing a new child.

In addition to prolactin, a woman’s hypothalamus also causes the release of oxytocin (via the pituitary gland) for the production of milk. Oxytocin is a catalyst in inducing labor so a female mammal can give birth. It is possible that birds also secrete oxytocin but more research has been done on rats and humans than on birds. Rats are often used in experiments because they are mammals, have a body and brain that is very similar to humans, and are much cheaper and easier to use for experiments than humans.

Beyond milk creation and inducing labor, the oxytocin neurotransmitter has the powerful affect of elucidating emotional bonding which results in the maternal drives required for child care. I suppose if we ever had a child, my boyfriend would probably help raise the newborn but he would not be producing oxytocin at the level that I am producing and would not feel the same level of chemical imperatives for nurturing.

Even though the human male’s brain keeps itself isolated from the nurturing drama by not releasing prolactin or extra oxytocin, there are other “potential” chemical activities that occur. In male voles, a rodent similar to a mouse, a hormone called vasopressin induces paternal care by the males. This study, however, has not been correlated to humans.

I watch the progress of the birds on my fire-escape and connect with the “maternal” instincts of the father pigeon. I do not see the mother much because it is too dark when she shows up. Since I am not pregnant, nor do I have a newborn, I do not have prolactin circulating in my system nor do I have an unusually high level of oxytocin. Oxytocin, however, is being released in my body consistently because I am in a committed romantic relationship (this chemical is not just for mothers, it is also released in humans when any bonding activities occur). I do not know for sure if the oxytocin in my body makes me feel more sympathetic to the pigeon parents but I suspect that it does. Either way, I am enjoying this pigeon child-care ritual.

Leena Prasad has a writing portfolio at http://www.FishRidingABike.com. Links to earlier stories in her monthly column can be found at http://www.WhoseBrainIsIt.com.

Dr. Nicola Wolfe is a neuroscience consultant for this column. She earned her Ph.D. in Clinical Psychopharmacology from Harvard University and has taught neuroscience courses for over 20 years at various universities.

References:

1. Bridges, Robert. Neurobiology of the Parental Brain. Academic Press 2008.

2. Numan, Michael; Insel, Thomas R. The Neurobiology of Parental Behavior. Spring 2011.

3. http://www.pleasebekind.com/pigeon.html

Nice!

Pingback: Septebmer 2012: Father’s Instinct |