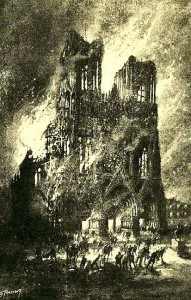

Rheims Cathedral, burning during the early days of World War I (G. Fraipont, 1915)

The Beast and Mr. James (an excerpt)

A play about Henry James and World War I, by Christopher Bernard

Act 2: 1914

London. Evening. A lobby in Covent Garden with stairs sweeping upward in the background; “Libiamo” from Verdi’s La Traviata is playing in the background.

HENRY JAMES is anxiously pacing the lobby, occasionally chewing a thumbnail. His hat and cane lie on a nearby lobby bench. He is dressed, with subdued elegance, for the opera – dark suit, light vest, elegant cravat, patent leather shoes, etc.

The music fades a little; a box door has closed.

HENRY JAMES (to himself): What did dear, kind Edith call me? A nervous nelly, with the imagination of disaster. Oh fie! I’m as nervous as a young cat. The worst can’t possibly be upon us – not now. They must settle something between them. They can’t be so mad as not to. They must see the stakes. Our countries are no longer run by lunatics and the brain-dead spawn of in-bred families. Common sense must have come to count for something in this bloody epoch.

USHER enters.

USHER (with a deeply reproving look; very loudly): Please, sir, be quiet so that the members of the audience can enjoy the music! Thank you, sir!

He leaves with a departing scowl at HENRY JAMES, who glares after him.

BURGESS, JAMES’s valet, dressed in outdoor ware, enters, carrying a newspaper.

HENRY JAMES (with a flushed hope, takes the paper; in a loud whisper): Thank you, Burgess, forgive me for driving you out in the middle of the night, but I just could not … (At sight of the front page, he lets out a cry, almost a shout.) No! … The Kaiser, that … no, no! …

He reads the column with moments when he pauses and stares over the top of the paper in despair, as the music continues in the background.

HENRY JAMES (with no attempt to be quiet): He’s mad! They are all mad!

He then takes his hat and cane and leaves hurriedly, with a gesture to BURGESS to follow, as the USHER re-enters, looking like thunder at them as they depart. “Libiamo” swells to a climax and ends, with wild applause.

Change of scene to:

A London street. Night. The sounds of clattering carriages and horses. HENRY JAMES and BURGESS get inside a carriage and it rides off; they rock back and forth inside.

HENRY JAMES: I … I can’t …

BURGESS (sitting next to him): Sir?

HENRY JAMES: I … don’t … it … (He looks at the newspaper again.)

BURGESS: Sir, is it about the assassination?

HENRY JAMES: Yes.

BURGESS: Is it about little Belgium?

HENRY JAMES: Yes.

BURGESS: Is it about the Kaiser?

HENRY JAMES: Yes, a thousand times, yes! The monster is mad. But they’re all mad. They’ve done the impossible. Maybe only the mad can do the impossible. Germany, France, Austria, Russia, now England – all of us will be at each other’s throats by morning. (Silence.) For what? It’s over. I can’t …. All of it, it’s … I … it … it’s springing … (He lapses helplessly into silence.)

BURGESS: What is springing, sir?

HENRY JAMES: … the beast …

The carriage rocks and creaks rapidly onward for a few moments before:

Change of scene to:

HENRY JAMES’s rooms in Carlyle Mansions. HENRY JAMES and BURGESS enter and HENRY JAMES throws his overcoat, hat and cane onto a chair.

HENRY JAMES (who seems in a state of shock): You saw the headline, Burgess. What did it say to you?

BURGESS (still in his outdoor coat; wonderingly): Say, sir? Why, it was plain as day, sir. It said we are at war.

HENRY JAMES: Plain as day, was it? Is that what it said? What I saw was this: “Today our civilization committed suicide. No one will win. Everyone will lose. This is the end of your world.” If Europe goes to war, that means the end of our civilization. That is what that means, and they all know it. It is no secret. It is not abstruse metaphysics, relativity, or the unconscious mind of humanity. It is as clear as the full moon in a cloudless night. That is why I can’t … believe it. It’s the strangest thing. They have just destroyed everything. I know it, and yet … I can’t believe it.

BURGESS: Well, I must say in that case I am very sorry to hear it, sir.

HENRY JAMES: Sorry? What have you to be sorry for, my poor boy?

BURGESS: You seem to be taking it so hard, sir. It seems like a close kin to you, sir. I’m very sorry for your loss.

HENRY JAMES: My loss?

BURGESS: Yes, sir. Civilization do seem to mean so much to you. St. Paul’s, Westminster Abbey, the Crystal Palace, the Royal Academy, the opry house, Prince Albert Hall, good books on the shelf, nice pictures on the wall – you know, civilization. It’s sad to lose it, I understand, sir, I cried like a baby when I lost poor Tom, my hoss, when I was a boy.

HENRY JAMES: Bless you, Burgess, your sentiments are most generous, but what I mean is not really the same thing, sad as it must have been, and very sorry I am that you had to lose it.

BURGESS: But we always have to lose it, don’t we, sir.

HENRY JAMES: Well, yes. I suppose you are right. But it’s not just the things you describe. It’s everything. And it is going bust, in a catastrophic, final way, like a home that was once filled with kindness and beauty and love, and also a lot of bickering, and sometimes much worse than bickering, but the old thing held up, it kept us up as we kept it, and now it is being swept away by a wave, an invading army in the night, an arsonist’s fire, and it is being done even when I, and many of us, felt it would be the very thing that would prevent it from going bust. Do you see?

BURGESS: I wish I did, sir. Those things are well and good, but they forget a few things too, sir, begging your pardon.

HENRY JAMES: Yes? And what do they forget, wise little Burgess?

BURGESS: They forget what made them, sir, and they can’t be better than what made them. And what made them, sir? People made them. And people are downright foolish, proud and blind and willing to believe anything that will make ’em feel well about themselves, no matter how silly, and refuse to believe anything that tells them what’s wrong with them, no matter how true. They forget the foolishness of people, sir. The deep dark lunacy at the heart, if you will permit me to say so, sir, of people.

HENRY JAMES (after a long pause): I’m ashamed. …

BURGESS: Sir? I didn’t mean to speak out of turn, sir, I am sorry if I …

HENRY JAMES: No, no, no. What you said was good, was right, it was quite perfect. I’m in your debt. Yes, truly. I’m the one who is wrong. But I’m dithering – it’s just such a blow. I can barely – I must write to Edith. She sees things I don’t. Maybe she can see some hope in all this. (To BURGESSS) I shouldn’t keep you. You can go now. I can take care of my things here. We’re home so much earlier than expected, you will no doubt be needed by Alice in the pantry. (He tries to smile.)

BURGESS (grinning): Yes, sir, thank you, sir. Oh, and I’ll tell the other staff, if that is all right with you, about the sad loss of your poor civilization.

HENRY JAMES: Yes, do that, Burgess. Thank you. (BURGESS leaves. Over the next speech, the scene changes to: Henry James’s drawing room at Lamb House in Rye, evening) The sad loss of my poor civilization! If he only knew – maybe it is better not to know. I wish I knew nothing. The mind suffocates in its own trap when it can’t cry the will into action. How blind I have been! Not to see, not to have seen … You, little Burgess, should not have had to read me that lesson. (He starts dictating a letter to EDITH WHARTON. She appears at a window at the back and seems to be listening to him.) Edith! What have I been writing about all my life? One would think I might have learned something after steeping my hands in the entrails of human selfishness, greed, hypocrisy, folly, lust for power, crimes – they would hardly stay caged in the souls of a few characters in a novel – not when I saw them in the hearts of myself and everyone I knew. I’ve been like a scientist who thinks the laws he has discovered in his laboratory stay in his laboratory. I should have seen it, expected it – the treachery, curled like a cobra in a man’s heart – a treachery directed, with the last irony, as much against himself as against his neighbor – exists as much in a general, a president, a king as it does in my enemy, my rival, my neighbor. … We all believed we had reached the peak of human progress, that certain things were no longer possible. And now the armies of Europe will fling themselves at each other without hope and without mercy. No, Edith, I lacked the imagination of disaster until it was too late. I should have felt the hawk’s cold wing. (A bird suddenly starts singing profusely in the Lamb House garden. HENRY JAMES drops the letter he has been writing and approaches the “French windows” (we are now in the Lamb House drawing room; it is evening) and listens.) To think we have never had a more beautiful summer. (The bird continues singing lustily for a time. At last it stops and flies off. HENRY JAMES’s eyes follow it as it flies away.) Fire is walking across the sea from the mouth of the setting sun. (Silence.) Farewell, peace, welcome, darkness.

BURGESS enters (he is wearing his normal at-home valet attire).

BURGESS (hesitantly): Sir? May I speak to you, sir?

HENRY JAMES: Yes, of course, Burgess. What is it?

BURGESS: I have been following the public events in the newspapers since the assassination of the Archduke Ferdinand and his wife in Bosnia, sir, and now with all the horrendous news from Belgium and France, and England declaring war against Germany and everybody, I have come to the conclusion that it is my simple duty to stand by my country in this its hour of need and to follow the colors and join the army. This is not an idle or a hasty decision, sir; as I say, I have been thinking about this matter for some time. But first I wanted to ask your permission, sir, before I take so important a step, especially as I realize it will cause you some inconvenience. Well, sir, that is what I have to say, sir.

HENRY JAMES (with some astonishment): Why, Burgess, I suspect that is the longest and most coherent statement you have ever spoken in your short life, and I must say you have spoken it beautifully. I commend your sentiments from the very bottom of my heart. More importantly I commend your action. If I were not 71 years old – say, a mere 69 – I would probably follow you or even better have pre-empted you! Yes, now is not the time to repine and recoil and lament – now is the time to act, to act decisively and bravely. Call in the rest – (He excitedly rings the bell for them.) Alice! Marshall! Come in, come in, we have the most exciting, the most important news.

ALICE and MARSHALL enter and stand gaping at HENRY JAMES and BURGESS, who stands facing the audience, looking a little self-conscious but straight as a soldier.

HENRY JAMES: Alice, Marshall – our Burgess … Well, Burgess, you tell them.

BURGESS: Right, sir. Well. I … I … I can’t say it so high and mighty as you, sir, I can only speak it plain. I … well, after seeing the little batch of soldiers from Rye march off to Dover a fortnight ago, I couldn’t bear the thought of not joining them. I’m joining the Old Contemptibles … I’m joining the army.

Sensation from ALICE.

HENRY JAMES: That’s right. He’s going to war to fight the Hun, overcome the madness of the Kaisers, and help us save Belgium and save Europe, and save our poor, savaged honor in this terrible war that is upon us.

MARSHALL: Well, I never!

ALICE: How handsome you’ll look, Burgess, in uniform, I daresay!

MARSHALL: You go knock some sense in those crazy Huns, Burgess! You send ’em back to Berlin! You give ’em hell, Burgess! (Begging your pardon, sir.)

HENRY JAMES (shouting): We’re off to war!

HENRY JAMES and BURGESS (shouting): We’re off to war! We’re off to war!

HENRY JAMES, BURGESS, ALICE and MARSHALL march around the room, singing:

We’re off to war! We’re off to war –

We’ll fight them anyhow!

We’ll take our places and our guns

And show the Hun just how

The British will not take a slap

Or any insult on the map –

We’ll fight him here, we’ll fight him there,

We’ll fight him like we had no care,

Until we sing for victory

From pole to pole and sea to sea!

Repeat two or three times, the final time with the following concluding lines:

Until we Triumph! Liberty

Will Be Our Prize. To Victory!

During the above, BURGESS changes into a uniform (say, with the help of ALICE and MARSHALL, the uniform, etc., “conveniently” kept in a nearby closet). At the end of the “song,” he is in full uniform, with boots, knapsack, rifle, bayonet, etc., and ready to leave for the front.

HENRY JAMES (to BURGESS): I feel so proud of you today, my boy. It’s like losing an arm or a leg to see you go, but I can see you are going to be a first-rate soldier, and nothing could give me greater pleasure. If it’s socks you will most need, we will keep you supplied, will we not?

ALICE: Yes indeed sir!

MARSHALL: Well, Alice will have to supply the socks, with your permission, sir. I warn’t to begin no darning, not this late in life.

They all laugh.

HENRY JAMES: You are excepted from darning duty, Corporal Marshall. (To BURGESS) Just let us know all your wants. We’ll keep your place here warm by the fire! Write when you can, but do not feel imposed to it. We will always be carrying you in our hearts. And you will be sure to visit us when you are on leave, and as soon as victory sounds before Christmas!

BURGESS: Yes, sir! To be sure, sir! You are most kind and generous, sir! And everyone … everyone … you are, you are, you are … like the family I don’t have.

HENRY JAMES gazes at him closely, pats him on the shoulder and smiles.

As they all turn to lead BURGESS to the back exit, ALICE and BURGESS furtively touching hands, there is a sound of distant booming. They all turn back and look toward the “French windows.” Freeze. Silence. More distant booming. They walk slowly, almost hypnotized by the sound, toward stage front. Note: they and the room behind them are lit by the setting sun.

HENRY JAMES: The Germans have reached France.

More booming. There is the sound of a woman sobbing.

ALICE (pointing down at the audience): Look, sir! It’s the Belgians.

HENRY JAMES (appalled): She’s carrying a baby. I almost forgot – I said I would let them have what I could for a refuge. I had no idea they would be here so soon …

Everyone again freezes, looking across the audience.

More booming. More sound of the woman sobbing.

ALICE: The sun is setting, sir. I should be closing the windows.

HENRY JAMES: No. Keep them open.

More booming, sobbing.

No one moves. Slow fadeout as the sun sets. The sounds continue for a few moments over the darkness.

Christopher Bernard is a writer, poet, editor and journalist living in San Francisco. His books include the widely acclaimed novel A Spy in the Ruins; a book of stories, In the American Night; and The Rose Shipwreck: Poems and Photographs. His work has appeared in many publications, including cultural and arts journalism in the New York Times, San Francisco Chronicle, Chicago Tribune, San Francisco Bay Guardian, Philadelphia Inquirer and elsewhere, and poetry and fiction in literary reviews in the U.S. and U.K. He has also written plays and an opera (libretto and score) that have been produced and radio broadcast in the San Francisco Bay Area. His poetry films have been screened in San Francisco and his poetry and fiction have been nominated for Puschcart Prizes. He is co-editor of Caveat Lector (www.caveat-lector.org) and a regular contributor to Synchronized Chaos Magazine.