-Ryan J. Hodge

For someone who enjoys a great story, is there anything better than a narrative that engages you from the very start? Imagine a world so rich you can almost smell the scents in the air, a delivery so clever it forces you to think in a way you never thought you would. I’m Ryan J. Hodge, author, and I’d like to talk to you about…Video Games.

Yes, Video Games. Those series of ‘bloops’ and blinking lights that –at least a while ago- society had seemed to convince itself had no redeeming qualities whatsoever. In this article series, I’m going to discuss how Donkey Kong, Grand Theft Auto, Call of Duty and even Candy Crush can change the way we tell stories forever.

What Pokémon Teaches Us About Coming of Age Stories

‘Coming of Age’ or ‘The Rite of Passage’ is a staple in literature. Some of the most successful literary franchises have centered around a neophyte being thrust into a world that is equal parts incredible and terrifying. From Treasure Island to Harry Potter, there is a quintessential and visceral connection with the audience to be exploited with plot structures that amount to little more than just explaining how the ‘world’ works.

This genre, typically, is associated with teens and ‘young adults’, who (while perhaps not facing trials quite so fantastic) are learning in parallel with the characters how their own world works. Such stories allow an escape from the mundane daily routines of suburban living and imagine what it would be like to grow up in a place altogether more exciting.

It is little wonder, then, why Pokemon exploded in the mid-nineties and still commands a strong and loyal following even today. While, on the surface, Pokemon is a silly little game about battling monsters; its stories are coming of age tales at their core. In this series; players must explore, study, and experiment in order to reach the objective of becoming a ‘Pokemon Master’.

The first element we’ll address is exploration. One of the hallmarks of youth is discovering all that the world has to offer, including the dangerous and forbidden. The call to adventure, even ill-advised adventure, is a strong one. Take The Hobbit (J. R. R. Tolkien, 1937) for instance. The weakest element of the plot is, perhaps, the fact that Bilbo Baggins simply allows himself to become a part of the dwarves’ adventure despite having no desire or qualifications that would predicate his inclusion. Yet, despite the many hardships that will befall him; not only he, but the audience, are determined to see the journey through. Conceivably, Mr. Baggins could have turned around and gone home at any point. Perhaps, in fact, that would have been the rational thing to do. But he simply must see what lies in wait at Mirkwood. He simply must see a dragon for himself.

It is this innate desire that drives the player in Pokemon. Just what is in Cerulean Cave? What is this supposed ‘cloud monster’ terrorizing Unova? Answering these questions constantly diverts the player from his objective of becoming a Pokemon Master and, in fact, it is arguable that even achieving that objective is merely incidental. The draw is not becoming a Pokemon Master in title, but becoming one in spirit. This is why defeating the ‘Elite Four’, the supposed end bosses of each game, at best represents a mile-stone in the player’s journey rather than its conclusion. For after the credits roll, new areas and greater challenges will make themselves available to the player.

In this fashion, being crowned champion of the ‘Pokemon League’ may represent a narrative parallel to college. While there is much social pressure and allure associated with earning a degree, a young person must realize that it only offers more opportunities to explore his passions; rather being an end in itself.

The next theme of Pokemon is: study. Part of the appeal of any young adult coming-of-age tale is the mystique surrounding the universe and what role everything in it plays. As one question is answered, ten more appear in its place. As the protagonist learns, not only do we –the audience- learn; but we arrive at yet more questions. A good author is able to anticipate most of those questions, but may fail even in some key regards.

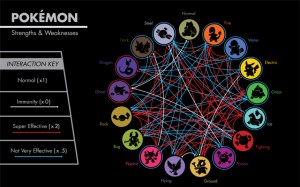

While Pokemon still contains enough vagaries that a thriving fan theory community has arisen, its nature as a game means that everything you *have* to know about Pokemon, you *will* know simply by playing enough. Pokemon’s primary gameplay conveyance exists in its incredibly robust combat system. Each unique Pokemon is assigned one or more elemental attributes which determine its effectiveness in a fight against other Pokemon. In a nutshell, it can be expressed thusly:

I imagine most readers come away from that chart extremely intimidated. The brave souls who even attempted to make sense of it might be asking themselves how ‘grass’ types can be effective against both ‘ground’ and ‘rock’ types. However, not only with the Poke Faithful be able to recite that elemental chart practically in their sleep, but can give a fairly accurate assessment of what a fight between any given two of the 719 currently extant Pokemon would yield based on the pairs elemental attributes, experience level, effort value training, and even breeding. For those readers who’d automatically assume that this is too much for any sane person to keep straight; I’ll remind them that these games are aimed primarily at children.

The reason child (and adult) fans are able to so readily grasp the byzantine web of considerations when building a Pokemon team is because the study of Pokemon is not only important in order for them to achieve their goals, but immensely fun! Remember: this is all self-taught for a player; he can give up any time. But millions of fans master these studies on some level of expertise.

Capturing the ‘fun’ of study is an immensely tricky thing for an author to do (heck, whole institutions dedicated to study haven’t managed it); mainly because study is rarely fun for anyone. Often, in narrative, the amount of study required to solve a problem is hand-waived with a montage, acknowledged as having been done at some point, or just having the protagonist be naturally gifted enough to solve the problem without study. However, the inclusion of a study element not only makes a work more grounded, it adds to the immersion of the story in that the audience will be solving problems along with the protagonist based on what they’ve learned. Captain’s Courageous’ (Rudyard Kipling, 1897) main plot centers around a shipwrecked boy who is forced to work on a fishing vessel. That’s it. Yet the work cleverly draws the reader in by depicting the boy slowly turning from a whiny, unlikeable brat to a well-adjusted young man all through the study of the fishing trade. As he learns; we learn, and as we learn, we begin to anticipate solutions to day-to-day problems. An audience that is able to use its knowledge to follow the story better is a more invested audience. The more knowledge that is cleverly imparted to them; the more they’ll hunger for it.

Finally, we come to the final these of the Pokemon titles. In the Venn diagram of ‘Exploration’ and ‘Study’, Experimentation lies in the middle. It is here where a great deal of investment for any reader or player will form. From tweaking a Pokemon’s skills during training, to distilling the ideal tournament-level team; there is going to be much trial, error, and competing theories.

In this way, the player can make his own mark on the world (which will be a strong theme of any coming-of-age tale) by combining what he knows for certain with what he believes could be true and eventually arriving at a validating result. One can be engrossed for months, even years, pursuing that result and –despite the fact that it’s all so many pixels and lines of code- still come away feeling accomplished.

While readers cannot truly be a party to such epiphanies, nothing gets an audience’s motor running quite like a ‘fan theory’. When done right, an author can introduce an equal amount of evidence supporting two (or more) mutually contradictory conclusions. Professor Snape’s status (Harry Potter series) as hero or villain is a fine example of this. Snape is portrayed primarily as a sadistic teacher who seems to have a very particular vendetta against the protagonist. Yet, in certain key respects, he ensures the protagonist survives otherwise fatal encounters. Why is he doing either of those things? That question was hotly debated by fans right up until the final book.

This carefully struck balance between the ‘unknown’, the ‘known’, and the ‘known unknown’ is the hallmark of the Pokemon series. Incidentally, these are also the key ingredients to a gripping coming of age tale: the introduction to an exciting yet alien world, the establishment of its rules and dictates, and the journey of self-discovery as one applies those rules to the vast sea of uncertainty in a fashion no one has ever tried before. When that Onyx steamrolls your Pikachu; you’re learning. When you know to pit Bulbasaur against a Geodude; you’re growing. So try to catch ‘em all! Who knows? It just might make you a better writer.

Ryan J. Hodge is a Science Fiction author and works for Konami Digital Entertainment US (His opinions are his own). His latest book, Wounded Worlds: Nihil Novum, is available now for eBook & Paperback.

You can now follow Ryan on Twitter @RJHodgeAuthor