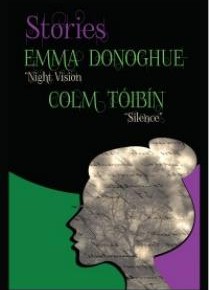

TWO STORIES ONSTAGE

Word for Word’s Stories

Emma Donoghue “Night Vision”

Colm Tóibín “Silence”

Z Below

San Francisco

San Francisco’s well-known drama group Word for Word, which for 23 years has been staging short stories with ever-increasing theatrical sophistication, recently brought to the stage two finely wrought tales by Irish writers about Irish writers at SoMa’s Z Below. The results were a pleasure for both lovers of literature and of the stage.

Word for Word’s cunning device is so obvious one wonders why nobody ever thought of it before: take a good short story and stage it as a play, with every word spoken by a character in the story. The opportunities for theatrical magic are patent, and potent, and taken entire advantage of by Word for Word and its talented staff.

Tonight’s embarking (I saw it on April 1st) brought two stories, one by Colm Tóibín, the comfortable, fashionable middle-brow writer (“middle-brow” is sometimes mistakenly taken for a putdown, though it isn’t; a sturdy literary culture needs a strong middle-brow culture to keep the low-brow aspiring and the high-brow honest), based on an anecdote from the notebooks of Henry James. The anecdote was told to him by Isabella August, Lady Gregory—the Lady Gregory—writer, playwright and Irish folklorist, probably most famous in this country for her association with the poet W. B. Yeats and their mutual support of the celebrated Abbey Theater, now the National Theatre of Ireland. Henry James never worked up the anecdote into a story, but Tóibín uses it to draw out a tale about an affair between the unhappy Lady Gregory and the poet and womanizer Wilfred Scawen Blunt, and her long, puzzled savoring of what seems to have been the one great physical passion in her life.

The story suffers a bit from a conventional setup—repressed Edwardians discover the body’s ecstasies through tea and adultery in a romanticized Orient (the affair begins in Cairo before gravitating to, and dying in, London)—and has its longueurs as Lady Gregory struggles to find meaning in what any Frenchwoman could have told her was never meant to have any. Lady Gregory finds that the end of the affair leaves her with a feeling of emptiness and futility, especially as she is unable to give any public acknowledgement of its (fleeting) existence. The story probes the soul’s demand that every private passion in some way be given public recognition (an almost redundant theme in the age of Facebook and Instagram, when trying to keep anything that one does private is almost as much as one’s life is worth), and it provides a curious, and imaginative, solution.

The staging was suggestively ornate; the costumier had a field day with the small, tight cast, juggling between Belle Epoque and full-throttle Orientalism. Sheila Balter (in her first of three performances in the role) was, despite a little unsteadiness, an engaging, sympathetic Lady Gregory in hungry youth, mortified maturity and disillusioned old age; and Rudy Guerrero was more than plausible as a romantic cad and seducer of the unhappy wife and, later on, a clueless Spanish flirt at an interminable London dinner. Robert Sicular brings Henry James to life as the ever-sympathetic listener, keen observer, and father-figure; Tóibín’s special feeling for James (he wrote a fine novel about the writer, The Master) comes through clearly, not only in a subdued pastiche of James’s style, but also in his liberal quotations from James’s writings, and in Sicular’s warmly civilized performance. Richard Farrell is appropriately tiresome as the civilized brute Lord Gregory. Jim Cave directed.

Though I mention it last, the best was first. The night’s program opened with Emma Donoghue’s profoundly poetic story, also about an Irish writer, called “Night Vision.” It is about Francis Brown (sometimes spelled with a final “e”), also known as “the Blind Poetess of Donegal,” who lived, and published both poetry and fiction, in the early half of the nineteenth century. Donoghue’s story, about the poet’s youth in an Irish country farmhouse; her struggles with, and odd joys in, her blindness; her conflicts with the miserable patriarchy of the land; her stubbornness and small, brave personal fight for her own spiritual survival—her discovery of her love for words, and so of her vocation—all of it, is told with rapturous and humorous and at times almost painfully honest poetry.

If ever there was magic in a story, and that magic was translated to the stage with faithfulness and ardor and wit, it happened here. The direction (by Becca Wolff) was vigorous and true; the stagecraft (including the use of scarf-like scrims and small back projections and a portable drape that served as a counter, a sill and a little stage curtain) withheld no enchantment; the ensemble acting (most of the actors were shared by both stories) was resourceful, as they divided among themselves whole sentences threaded with Donoghue’s linguistic pearls just muddied enough to give fantasy the aroma of reality. And the performance by Rosie Hallett as the young blind Franny was detailed, judicious, quiet and unforced, carefully thought through—not merely heartfelt, but heart-touching without seeming effort—in short, inspired.

_____

Christopher Bernard is author of the novel Voyage to a Phantom City, the play The Beast and Mr. James, the collection Dangerous Stories for Boys and The Rose Shipwreck: Poems and Photgraphs. He is also co-editor of Caveat Lector.

Pingback: editorial letter for May: Herding Cats | Synchronized Chaos

It’s hard to locate knowledgeable people on this matter, but you seem like you know what

you’re talking about! Thanks