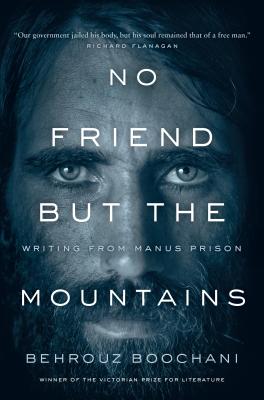

Review of No Friend But the Mountains, by Behrooz Boochani

The seamlessness of borders, and the seamlessness of bodies; these are one in the same in the opening words of No friend But the Mountains. For, as we begin this book, after what appears to be many months of pointless fleeing, on foot, by truck, we are on a boat, in Boochani’s mind, along with several other people fleeing persecution in their countries, lost in the swish-swash of the sea.

The sea swells as it bends, it burns as it also churns. Such is the great power of equity; to render all in the horizon as infinite, to make it all feel like endlessness, to take many bodies, from many corners of the world, and to make them on this boat One Thing. In this case the word we give to these people, who were previously Kurdish, or Sri-Lankan, or Burmese, is ‘refugee.’ A person who is state-less. A person who happens to be in between countries.

In Boochani’s case, this is not the transnational-ness of a privileged First Worlder or even of an intellectual exile. Just for wanting to flee ethnic persecution, Boochani is immediately sent to Manus Island, Australia’s answer to Alcatraz. It is a grueling and harsh prison ruled by the most militant of guards. We see fathers of an old age lose their children, the dignity beaten out of people who were once the proudest, and the most flamboyant of characters, stripped to the peels of what they once were.

Boochani chooses to tell his tale in chapters, with strips of first person narration interrupted by sparse, poetic reflections. The language of the narration itself is professional, insightful, and well-crafted. I was struck often by the simpleness and yet beauty of sentences, such as on page 78 of my Kindle edition, “I was probably the lightest traveller in the history of all the world’s airports. It was just me, the clothes on my back, a book of poetry, a packet of smokes, and my manhood.” Another one was on page 143: “A killer is a killer; violence oozes out through their blurred, diluted pupils. I’m convinced that the soul of a killer is reflected in their eyes.” Like seashells on the coast, sentences like these are everywhere in the book. Whether this comes from the innate Persian of the original manuscript or the translator’s hidden talents is hard to gleam, but regardless, the coarse rifts of insight studded through the language made this a stunning text to read.

As per the poetic interludes which bifurcate the text, I had more mixed thoughts. In general, I enjoyed the musings on nature, life, and thought, but the amount of ones which felt earned were less than the ones that were repetitive and self-indulgent. With certain stylistic choices, I think it is always best to err on the side of less than more, and to choose the ones with the most poetry and thought behind them. The one which I thought was the most impressive was Boochani’s invocation of the mountains in a pattern of a dream.

“The ruckus of our terrified group / The sound of weeping in the background / The beating of waves / The petrified, silent screaming / The tormented wailing / Waves rocking a cradle containing a corpse / All within a domain of death and darkness / My mother is present / She is there alone / Travelling over the ocean or emerging from within the waves? / Where is she? / I don’t know / I only know she is there / Alongside me / She is afraid / She is smiling, and she is weeping / Shedding tears from years of sorrow / I don’t know / Why is my mother cheerful? / Why is she weeping? / I witnessed a wedding celebration with rituals of dance / I witnessed lamentations that dictated demise / Where could this place be? / Grand mountain peaks covered with snow, full of ice, abounding in cold / I am there / I am an eagle / I am flying over the mountainous terrain / Over mountains covering mountains / There is no ocean in sight / From all ends, the territory is completely dry / The presence of ancient chestnut oaks / The presence of my mother / She is always present.” (p. 29-31)

In the case of this particular transition, Boochani’s fleeting language creates a willful transition between the puncture of the boat and Behroonani waking up after. It inserts some surrealism into an otherwise grounded story, and the transition works in setting up the scene that follows after, Boochani being very much in prison. The others were sometimes too pseudo-poetic. For example,

“I am on the threshold / Entering the labyrinth of death / Perhaps the essence of death involves war / Both living and dying at once / I swim through my own hallucinations / All these images / The constructions of my own mind.” (p. 39)

Boochani has these thoughts right as he is entering the water again while a guard chases him. The scene would have been much more interesting if Boochani took the risk of describing the brunt way he is fished out of the ocean, but instead, the poetic interlude undercuts the drama and makes it feel abstract.

Though, I would have preferred more graphic descriptions of the boat going under that more pseudo-poetic underlines.

Characters are not given names in Boochani’s books, but archetypes. In a book like this one, where people have had their humanity humiliated, but are still very much human through and through, I personally believe this works to great effect. It also made certain characters stronger for me. There was Maysam the Whore, a flamboyant dancer who could have easily been a character out of a Dostoevsky novel. Maysam the Whore is both shamelessly flirtatious, and also the proud source of many a tease. The story of the Father of the Months Old Child is realistic and all the while heart-breaking. Boochani’s abilities to characterize are impressive, and I would love to see what he would do if ever he wrote a novel. Each of these characters who are never given name are given more than that: they are entire identities, as well as entire entities.

All in all, No Friend But the Mountains is one of the best books that I have seen published in the last few years. I don’t know if it is emblematic of the sad fact that memoir is often more powerful than fiction these days, or if it is because Boochani and his translator are just that talented of a team, but the observations on each and every page are enough to fill term papers on, and one could spend equally as many hours reflecting on the narrative’s embedded poetry. The book finally ends on a rebellion set on the prison. Like Odysseus facing the Cyclops or Arjuna facing Karna, the prisoners, the aboriginal Papus, and the Australians face off as well, giving the sense of tension akin to the best of ancient literature. Humans fight for their lives, as well as for what they believe to be right, but most importantly, the dignity of love. After all, what is life without hope? And what happens to that hope, if it ends before it has been given the right to inspire, or to the right to show its light?

Boochani, Behrouz. No Friend but the Mountains (pp. 29-31). House of Anansi Press Inc. Kindle Edition. Available here.