Developing critical thinking in higher education

Uzbekistan World Languages University

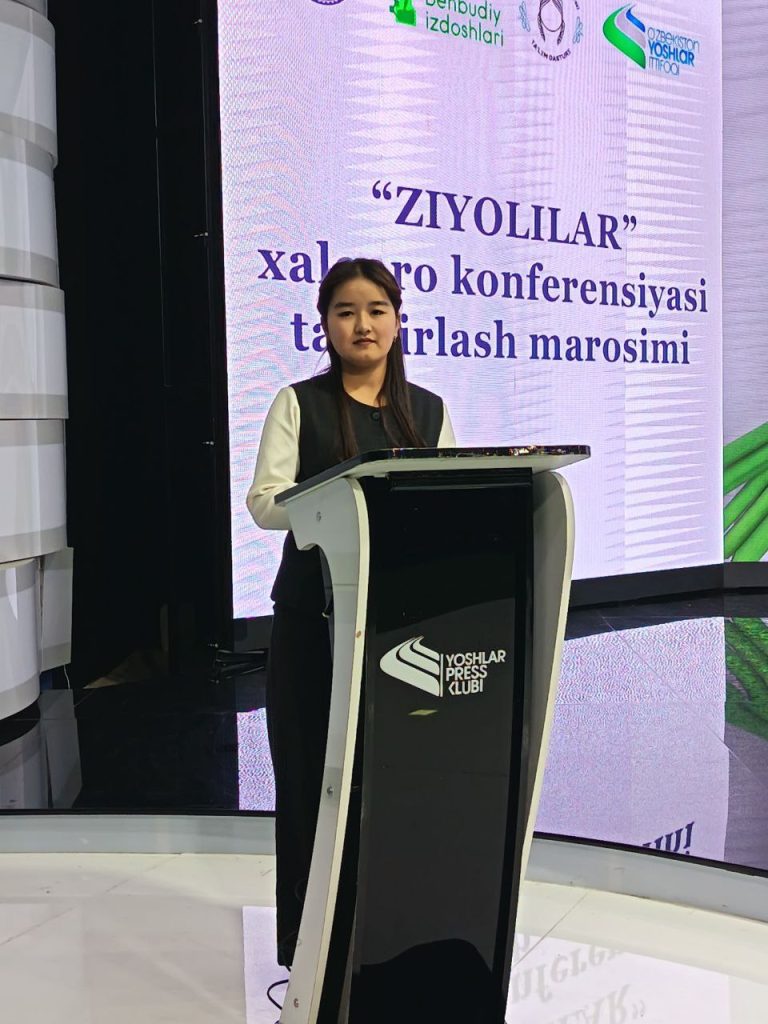

English philology faculty, 2nd year student

Ne’matullayeva Mukhlisa Sherali kizi

nematullayevam8@gmail.com

Abstract: In the context of modern higher education, the development of critical thinking skills has become a central objective of academic instruction. As universities prepare students for complex professional and social environments, the ability to analyze information, evaluate arguments, and make reasoned decisions is increasingly essential. This article explores the concept of critical thinking and its significance in higher education. It examines key components of critical thinking, including analysis, evaluation, reflection, and problem-solving. Drawing on educational and cognitive research, the study discusses common barriers to the development of critical thinking, such as passive learning methods, overreliance on memorization, and limited student engagement. The article also highlights effective pedagogical strategies for fostering critical thinking, including active learning, discussion-based instruction, problem-based learning, and reflective practices. Overall, the article provides a structured framework for integrating critical thinking development into higher education and enhancing students’ academic and intellectual independence.

Keywords: Critical thinking, higher education, analytical skills, problem-solving, active learning, student engagement, reflective thinking, academic independence.

Аннотация: В условиях современного высшего образования развитие навыков критического мышления становится одной из ключевых задач академического обучения. Поскольку университеты готовят студентов к сложной профессиональной и социальной среде, способность анализировать информацию, оценивать аргументы и принимать обоснованные решения приобретает особую значимость. В данной статье рассматривается понятие критического мышления и его роль в системе высшего образования. Анализируются основные компоненты критического мышления, включая анализ, оценку, рефлексию и решение проблем. На основе педагогических и когнитивных исследований обсуждаются распространенные препятствия развитию критического мышления, такие как пассивные методы обучения, чрезмерная ориентация на заучивание и ограниченная вовлеченность студентов. Также в статье выделяются эффективные педагогические стратегии формирования критического мышления, включая активное обучение, дискуссионные методы, проблемно-ориентированное обучение и рефлексивные практики. В целом статья предлагает системный подход к интеграции развития критического мышления в высшее образование и повышению академической и интеллектуальной самостоятельности студентов.

Ключевые слова: критическое мышление; высшее образование; аналитические навыки; решение проблем; активное обучение; вовлеченность студентов; рефлексивное мышление; академическая самостоятельность.

The mission of higher education in the twenty-first century extends far beyond the transmission of disciplinary knowledge. Universities are increasingly expected to develop graduates who can think independently, evaluate information critically, and respond thoughtfully to complex global challenges. In this context, critical thinking has emerged as a cornerstone of academic excellence and lifelong learning. The rapid expansion of digital information has transformed the learning environment, making students more vulnerable to superficial understanding and passive consumption of content. Without well-developed critical thinking skills, learners may struggle to distinguish reliable information from misinformation, synthesize diverse perspectives, or construct coherent arguments. Therefore, fostering critical thinking is not only an academic necessity but also a societal imperative. This article seeks to examine the nature of critical thinking in higher education and explore systematic strategies for its effective development.

Theoretical foundations of critical thinking

Critical thinking is commonly conceptualized as a form of higher-order thinking involving analysis, evaluation, inference, and self-regulation. According to Facione, critical thinking consists of both cognitive skills and dispositional elements, such as intellectual humility, open-mindedness, and persistence. These dimensions interact to enable individuals to engage in purposeful and reflective judgment. From a constructivist perspective, critical thinking develops through active engagement with knowledge rather than passive reception. Learners construct meaning by questioning assumptions, testing hypotheses, and reflecting on outcomes. In higher education, this process is supported through academic discourse, research-based learning, and exposure to multiple viewpoints. As a result, critical thinking becomes a dynamic intellectual practice rather than a fixed skill.

Cognitive and metacognitive components

Critical thinking involves a range of cognitive processes, including interpretation, analysis, evaluation, and synthesis. However, these processes alone are insufficient without metacognitive awareness. Metacognition allows students to monitor their own thinking, recognize cognitive biases, and adjust strategies accordingly.

University students who develop metacognitive skills demonstrate greater academic independence and deeper engagement with learning materials. They are more capable of identifying gaps in understanding, evaluating the strength of arguments, and revising their perspectives. Consequently, metacognition serves as a bridge between knowledge acquisition and critical application.

Methodological approach

This article adopts a qualitative analytical approach grounded in a review of interdisciplinary educational literature. Key theoretical frameworks and empirical studies on critical thinking development were examined to identify recurring patterns, challenges, and effective instructional practices. Sources were selected based on relevance, academic credibility, and applicability to higher education contexts. The analysis focuses on synthesizing existing research rather than conducting experimental investigation. This approach allows for a comprehensive understanding of critical thinking as a multidimensional construct influenced by pedagogical, institutional, and learner-related factors.

Barriers to critical thinking development

Despite its recognized importance, critical thinking remains insufficiently developed in many higher education systems. One significant barrier is the dominance of teacher-centered instruction, which positions students as passive recipients of information. Such environments limit opportunities for questioning, discussion, and intellectual risk-taking. Assessment practices also play a critical role. When examinations prioritize factual recall over analytical reasoning, students are discouraged from engaging in deeper learning. Psychological factors, including fear of failure, low self-confidence, and limited academic autonomy, further constrain critical engagement. These barriers highlight the need for structural and pedagogical reform.

Instructional strategies for enhancing critical thinking

Effective development of critical thinking requires intentional instructional design. Active learning strategies, such as debates, case studies, and collaborative problem-solving, promote analytical reasoning and perspective-taking. These methods encourage students to articulate arguments, challenge assumptions, and evaluate evidence. Problem-based learning (PBL) is particularly effective in higher education, as it situates learning within authentic, complex problems. Through inquiry-based tasks, students develop reasoning skills and connect theoretical knowledge to real-world contexts. Reflective practices, including journals and self-assessment, further strengthen metacognitive awareness and intellectual responsibility.

Curriculum integration and institutional responsibility

For critical thinking development to be sustainable, it must be embedded within curriculum structures rather than treated as an isolated objective. Learning outcomes should explicitly emphasize analytical and evaluative competencies, while assessment criteria must reward depth of reasoning and originality. Faculty development is equally essential. Educators require training in designing tasks that promote higher-order thinking and facilitating meaningful academic dialogue. Interdisciplinary learning environments also enhance critical thinking by exposing students to diverse epistemological perspectives.

The findings of this analysis suggest that critical thinking development is a complex, multi-layered process influenced by instructional practices, institutional culture, and learner motivation. While individual teaching strategies are effective, their impact remains limited without systemic support. A holistic approach that aligns pedagogy, assessment, and curriculum design is therefore essential. Developing critical thinking skills in higher education is a strategic priority for preparing students to meet academic, professional, and societal challenges. This article has demonstrated that critical thinking underpins intellectual autonomy, academic success, and lifelong learning. However, its development requires deliberate pedagogical planning and institutional commitment. By adopting learner-centered approaches, reforming assessment practices, and integrating critical thinking across curricula, higher education institutions can cultivate reflective, adaptable, and responsible graduates capable of navigating an increasingly complex world.

References:

- Facione, P. A. (2011). Critical Thinking: What It Is and Why It Counts. Insight Assessment.

- Paul, R., & Elder, L. (2006). Critical Thinking: Tools for Taking Charge of Your Learning and Your Life. Pearson.

- Brookfield, S. D. (2012). Teaching for Critical Thinking. Jossey-Bass.

- Halpern, D. F. (2014). Thought and Knowledge. Psychology Press.

- Kuhn, D. (1999). Educational Researcher, 28(2), 16–25.

- Biggs, J., & Tang, C. (2011). Teaching for Quality Learning at University.

- OECD. (2019). Future of Education and Skills 2030.

Muxlisa Ne’matullayeva was born on November 4, 2006. She is a second-year student at the Faculty of World Languages, where she is developing strong skills in foreign languages and intercultural communication. Muxlisa is known for her dedication to learning and her interest in global cultures. She strives to broaden her knowledge and build a successful future through education and continuous self-improvement.