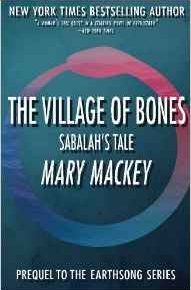

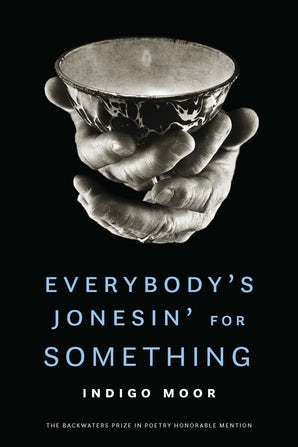

Poet Laureate Emeritus of Sacramento, Indigo Moor’s fourth book of poetry Everybody’s Jonesin’ for Something, took second place in the University of Nebraska Press’ Backwater Prize. Jonesin’ is a multi-genre work consisting of poetry, flash fiction, memoir, and stage plays. His second book, Through the Stonecutter’s Window, won Northwestern University Press’s Cave Canem prize. His first and third books, Tap-Root and In the Room of Thirsts & Hungers, were both parts of Main Street Rag’s Editor’s Select Poetry Series. Indigo is an adjunct professor at Dominican University and visiting faculty for Dominican’s MFA program, teaching poetry and short fiction. He is also co-coordinator for Open Page Writers.

Mary: Welcome to Synchronized Chaos Magazine, Indigo. Let’s cut to the chase: How did you become a poet?

Indigo: I don’t know. By birth? Circumstance? My entire life, I sought explanations, keys to what I saw around me. That’s all any artist is: someone who can’t be satisfied with leaving the rock unturned. In that sense, I have always been an artist of some kind. If you are asking when I became a practicing poet, it was 1999. What should I call that, my Prince year? I was in Cambridge, MA, trying to figure out who I was. I discovered Paul Robeson. I discovered Othello. I discovered that poetry was not only something I did; it was who I am. I made a conscious decision to dedicate a significant amount of my life to bending toward the written word. Or bending it to me.

Mary: How old were you when you wrote your first poem, and what was it about?

Indigo: As a kid, in school. Even then I knew it meant more to me than it did to many of my friends or classmates. I hungered for it. It was an awakening. But there was no avenue to get me closer. No shortcuts. No mentors. I had other paths to follow. I wrote a lot of bad poems as a child. I remember snippets of some, but nothing that could give me a glimpse of any of them.

Mary: What poets and writers have influenced you?

Indigo: Yusef Komunyakaa was the first to speak to me. He is Southern, a veteran, someone who worked through himself to rewrite the world he knew. “Blackberries” and “Believing in Iron” come to mind. Dien Cai Dau, his book about Vietnam was my introduction to arc. Jean Toomer was next. He went back to the South to write Cane, again the theme of discovering yourself. I like many poets and I read widely. But I gravitate to poets who write themselves into being.

Mary: What events in your life or in society as a whole have influenced you? For example: You are a twice-decorated Gulf War Veteran, a playwright, a Professor at Dominican University, and an Integrated Circuit Layout Designer. Do you incorporate all these experiences into your poetry?

Indigo: I have been working on a memoir, so the different parts of my life are coming together. I would say nicely, but anyone who has written a memoir knows better. Layout designer has never been something that has reached my creative side. I am often asked if there is an overlap. Not that I have noticed. There is no poetry in engineering. But the person who writes poetry can be the same person who is an engineer. And a veteran. A professor. And a person who wears bunny slippers. It all influences me. But I choose what I write about. I am relearning who I was and what I went through during Desert Storm. And as a child. It is all coming together, but not as several rivers converging. More like a dozen different flowers growing in the same planter. Some thrive and have purpose. Some are support, even dying to enrich the soil. Some having no effect, other than preventing a nothingness. That is not entirely fair. There are some things that I thought were dead, that have resurfaced as meaningful events. And others I may never uncover.

Mary: How do you get the initial idea for a poem?

Indigo: It’s usually an image. My work is very imagistic. A new phrase can do so much. Today I heard: “Avoiding the Wagon.” When I found out the wagon in question was something that takes away a dead horse it began a train that will end in a poem. I spent time on a horse farm. It is one of the most life-affirming events of my life. And the idea of this wagon coming still chills me.

Mary: You are a poet who “weaves together historic truths.” How do the poems in your new book Everybody’s Jonesin’ for Something demonstrate this?

Indigo: History does not represent the past. Not to me. Taken as an “event,” anything can be glossed over, any moment. What I strive to find is the emotional event, the moment on one person’s life that history changes. A person decides to shoot up a church. As they sit in the car, what is going through their mind? A farmer hears of Trayvon Martin, how does it affect them? A woman receives a saxophone from her estranged mother. A painter tries to undo the Twin Towers falling on his canvas. History is only history when we forget it is more than a factoid. When we refuse to hold it in us, keeping it at arm’s length.

Mary: How has your poetry changed over the years?

Indigo: I believe my poetry changes as I do. As my lens focuses on different aspects of the world, so does my poetry. How I write changes because I learn different techniques. Everybody’s Jonesin’ for Something contains poetry, prose poems, flash fiction, flash memoir (did I make that up?), and stage plays. The entire book is one interlocking poem about the danger and draw of the American dream. Ten years ago, none of these poems, nor the concept of the book would have made sense to me.

Mary: Tell us more about Everybody’s Jonesin’ for Something.

Indigo: I wrote Everybody’s Jonesin’ for Something to explore my own understanding of the American Dream, which cannot be defined. We are all the heroes of our own stories. The American dream distorts depending on where the desire is spawned. The book is multi-genre because not all desires are best represented in poems.

Bethany Humphries, Editor-in-Chief of the American River Review said, “[Everybody’s Jonesin’ for Something is] no white-washed children’s textbook treatment of U.S. history. . . . It requires the reader to witness the offender’s hand reaching up Lady Liberty’s coppery skirt, to both confront abusers, and to empathize with a litany of memorable victims and survivors. . . . Utilizing a stunning variety of forms to explore a myriad of facets of human desire, from floating tercets to prose to dialogue-heavy scripts to a poetic table of historical footnotes, Indigo Moor delivers unforgettable images like chains ‘hanging like man-o-war tendrils, / like a trembling curtain of almost lynchings.’ There may be times you want to look away, but there are many moments you will want to return to, again and again.”

Mary: What are the three most important poems in Everybody’s Jonesin’ for Something? Why?

Indigo: There is never an answer to that question. Different poems have different meanings at different times, even to me. “Love Letter to Dr. Ford, from the Patriarchy” gave me a chance to step into the shoes of an institution I detest. To look atrocities as necessary to the survival of an America I am forced to walk through. The play “Catching a Cotton Ball” follows a couple at odds with each other as well as the country that doesn’t accept them. Veterans of Foreign War’s is more personal, pertaining to my own brother and how losing him is an everyday emotionally charged event. I like the range of these three pieces. Such different forms. Different agendas.

Mary: You were the Poet Laureate of Sacramento from 2017 to 2019. How has your involvement in the Sacramento literary community influenced your work?

Indigo: I don’t know if working with any organization influences my work. There are some fractured, but necessary groups in this region. Sacramento Poetry Center has been a stalwart in this community. I think what I am reminded of is that the community and serving the people is what matters.

Mary: If you could ensure that one of your poems would survive to be read 500 years from now, which poem would it be, and why have you chosen it?

Indigo: Yes, I can choose a poem, but only because it means something to me. “Metal: The Tow Truck Driver’s Lament,” from Tap-Root. It was the first poem where I tackled who I believed I was at the time. I think poems are asymptotic to the truth, at best. It speaks to stress and pressure, the belief of being alone in handling far too much. Of the hard road of the past and steam building. It worked for me. Perhaps a little too long to read. But certainly, a cathartic piece.

Mary: Thank you, Indigo. This has been fascinating. Do you have any upcoming readings or classes? How can people get in touch with you?

Indigo: Thank you, Mary. I’ll give you some contact information and you can post it at the end of this interview.

Contact Information for Indigo Moor and links to his writing:

Website: https://www.indigomoor.org

Everybody’s Jonesin’ for Something: To Order

For appearances: Workshops and Readings: https://www.indigomoor.org/appearances

Read Indigo Moor’s essay on how he became a poet: “A Long Overdue Apology” (part of the Marsh Hawk Press Chapter One Series)

And read “A Riotous Anodyne,” his brilliant open letter to the City of Sacramento on the occasion of the 2020 Black Lives Matter protests.