Ibn Halal: A Man with a Vision

Interviewing Ibrahim Fakhr, the modern Egyptian TV “street” director

Last Ramadan, the drama season in Egypt was steaming with interesting series and post-modernist comedies. One that particularly caught my attention was Rasayel – Messages in which an Upper Middle Class woman’s car crashes into a mysterious rich young man’s car, they both go into a coma where she later awakens with psychic powers, temporarily connected to the man’s dark past.

Spectacular shots, stable camera movements, and adept direction of the actors onscreen, all these elements drew me to find out how director Ibrahim Fakhr’s career led him to this particular success.

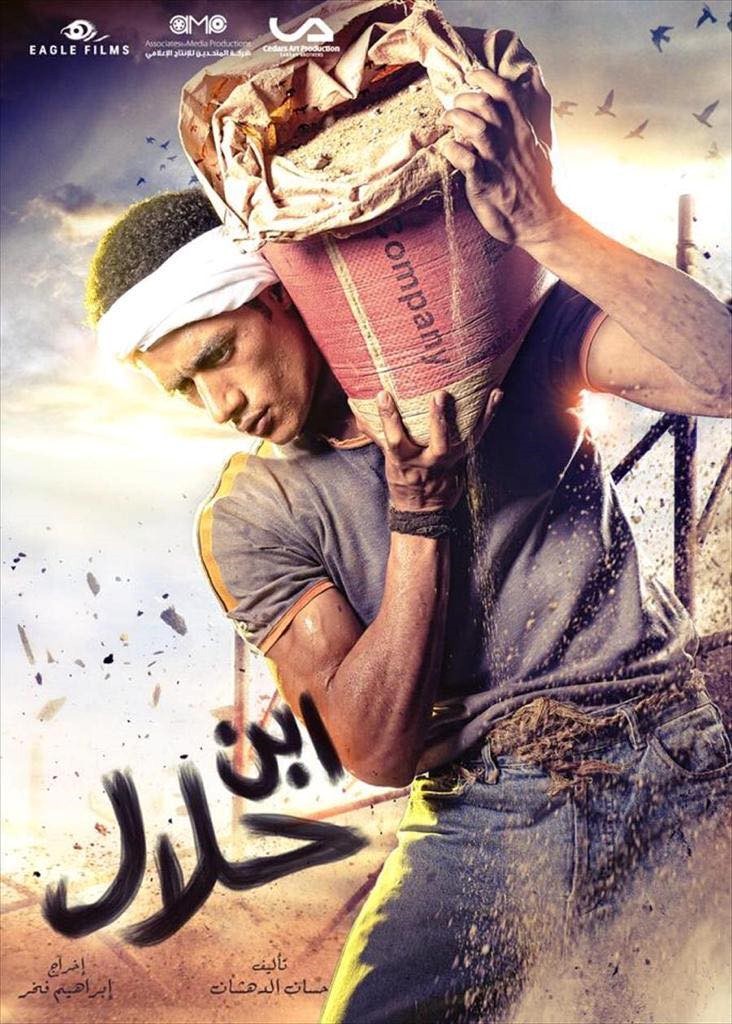

Informative, highly technical with a lot to tell about his actors and directing style, Ibrahim Fakhr knows what he wants, adding a unique input to every series that he directs. Picking mostly controversial topics in his directorial projects, Fakhr has never been ashamed of rooting for the underdog. His stories made heroes out of thugs and those who lived on the margins of the society. His most successful series to date Ibn Halal – Goodfella, starred Egypt’s most controversial movie star Mohamed Ramadan as the titular character, the goodfella Hebesha, whose Scorsese-like story of a good guy gone rogue spanned icky topics such as political corruption, sexual obsession and police brutality in the Mubarak era.

“Most directors started their career plans as actors, I did not plan anything. I simply wanted to be part of the glamor but deep down I wished I could be a theater actor. It was difficult submitting to the actor life, though. I am an authoritative person, a leader by nature and hated taking orders from directors. I am a Pisces so you can imagine how hard it is to try and tame that particular personality type.

While acting, I hated remaining mise-en-scene bound; the worst discovery was that as an actor, I did not have the liberty according to how I envisioned the scene, but according to the director.”

Fakhr started his career early from his schooldays, when he directed plays for the school theater and the university theater such as Hercules and the Augean Stables by Friedrich Dürrenmatt and Qaraqosh the Jester by Egyptian playwright Al-Sayed Hafez. Then he got his first job –while studying accounting in college– as assistant director with veteran TV director Mrs. Inaam Mohamed Ali, working together on one of her epic TV series, Qasim Amin in 2002; a semi-autobiography of the Islamic Modernist and jurist’s eventful life as the first feminist leader and among the most notable thinkers in the Arab world. Mrs. Ali’s resume included a myriad of similar projects. Being one of the few female directors in the Arab world, Mrs. Ali has always taken over major directorial projects; an epic, emotionally-charged War movie The Road to Eilat, a semi-autobiographical TV series chronicling the life of the legendary Egyptian singer Umm Kulthum which gained wide critical acclaim and took the Egyptian streets by storm. TV platform was a different place back in the early 2000s than it is now in 2019; with modest dramas conquering, mostly addressing conservative familial and middle-class age groups.

Mrs. Ali has not been given due proper credit yet. Throughout her career, she has made a major impact on the Arab drama, backing up projects with female-centric storylines, supporting female progress and feminism through multiple works such as Qessat El Ams – The Story from Yesterday which starred one of Egypt’s top leading ladies back then Elham Shahin in the role of a woman who ends her marriage to the man she loves because she discovers his polygamy, despite loving him. The series polarized audiences for perfectly portraying a regular Egyptian family and how destructive polygamy is to a woman’s self-confidence and the wellbeing of the average Egyptian family.

“In Mrs. Inaam’s school, I learned to excessively prepare, and pay too much attention to even the smallest detail. Shooting Qasim Amin took a year and 8 months, the overall experience was mesmerizing, she is a very talented director. She would order me to go to Al-Ahram Newspaper Archive for research and then we would start auditioning actors based on how they resembled their historic counterparts. I was assigned various books to read and research before shooting. Through her, I fell in love with the process. I found it an immersive stage where you start from scratch until imagination turns into reality. I saw the fourth wall broken when I became part of the set and witnessed the power of creating a work of art from nothingness.”

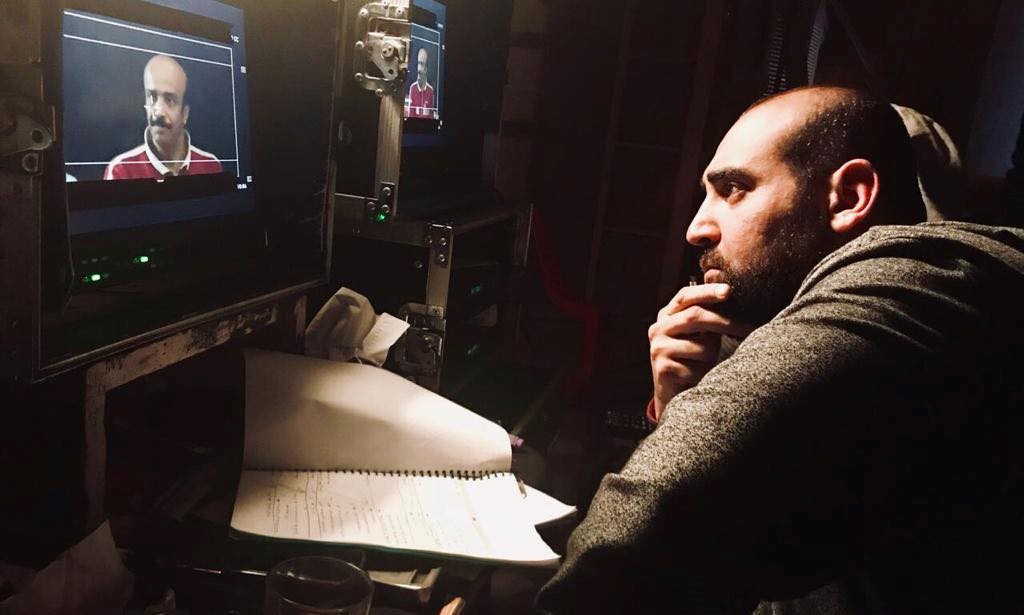

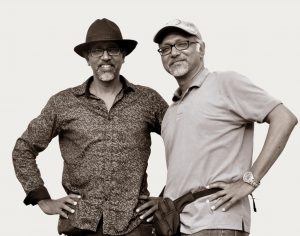

Ibrahim Fakhr with Amr Mcgyver, the famous Egyptian stunt driver, while directing the car accident scene in Rasayel TV series

For 10 years Fakhr worked on 3 TV series only; including a third assistant job (accessories assistant director) responsible for every item of accessories in the historical series Ibn Al-Haitham about the famed mathematician. Until his big break came as assistant director for veteran TV director Sherine Adel working together on Share’ Abdel Aziz – Abdelaziz Street which chronicled the life of one of the famed street inhabitants especially Eyad, the protagonist, played by audience favorite back then; Amr Saad. Abdelaziz Street is one of the most culturally significant streets in Cairo, not for the historical poignancy but more of its modern relatability to most Cairo residents; it’s your go-to when it comes to hardware, appliances, mobile spare parts and accessories. The series made the street even more iconic than it actually was and the experience for Fakhr, was also life-altering;

“This was the first time I worked in a set where the director used cinema-style in directing; using the one-camera technique instead of multiple, separate cameras which defined the traditional TV direction style. This was my first job as 1st assistant director,”

Interviewing Fakhr gave me the privilege of getting introduced to multiple terms that were otherwise unfamiliar to the non-experienced ear. He outlined the difference between first, second and third assistant director.

The third assistant director is called the accessories assistant director. His job demands a highly responsible and detail-oriented individual. He has to keep track of every item used by actors.

The third assistant director is responsible for every item from the moment it leaves the production line until it reaches the set. His responsibility also lies in keeping the Raccord – or match cut as they call it in English- which is how actors’ clothes, accessories, posture and elements in the setting should match if the same scene was shot multiple times.

The second assistant director is responsible for clothes. As for the first assistant director, his responsibility lies in being the director’s eye in the location; so while the director stays in the control room, the first assistant director handles decoupage –assembling the set of images/shots together to convey the story’s narrative, in simpler words the editing of the series- actor movements, scenes, shots manages cinematographers, follows up with the actors and reports to the director back in his lair. This is in addition to the continuity boy (script movement as they call it) who would be responsible for making sure that decoupage has been executed according to the script and the rules outlain by the director such as character movement from every single angle.

“My first time as a first assistant director gave me the opportunity to try my hand at directing. It was an amazing feeling. I was widely praised despite the tight shooting timeframe in Ramadan. I excelled because my experience with Mrs. Inaam taught me a great deal about montage, editing, learning how to edit and mix scenes so it was easy for me to put what I learned down to practice.

I play the flute professionally, so I had trained my ear to detect how each music piece fits a certain shot. I would give professional music and sound design recommendations.”

It was not long before Saad, the main protagonist and a mega movie star noticed Fakhr’s attentiveness to detail,

“I remember him telling me that I was helluva craftsman. He wanted me to direct his upcoming TV project Khorm Ebra – Hole of a Needle. It was my first opportunity to see that my vision becomes a reality. Amr was keen that I would be responsible for it due to multiple reasons; he was impressed with the results of the first two episodes –which we shot as a test- he knew that I was passionate about the story and fully understood it, and I had good communication with the scriptwriter. But my creativity was still under test.

Ibrahim Fakhr directing a scene from his 2018 masterpiece Rasayel

It was my debut directorial project and also Hassan Dahashan’s –the scriptwriter- first project. We lined an impressive cast with estimated 1300 scenes to be shot. This is almost as big as a movie. I wanted the directing style to be fast-paced, short scenes, with three or four plot twists occurring.”

Saad’s character Saeed El Brens was portrayed as a young man passionate about the New era of Egyptian music; the mahraganat –literal translation of the word is festivals- music genre which combines autotuned vocals with synthetic beats, which both support lyrics explicitly recounting the life on the streets of the narrow, thickly populated area slums.

“This is where the idea came for Amr to sing a mahragan. His brother [Ahmed Saad] is already an established singer of sha’abi music so he supported Amr and thus Bye, Bye Dough – Ma’a el salama ya floos was born as a political commentary mahragan. We featured some of the stars of mahraganat such as Gandhi, 50, and Sadat.”

What I liked about the song was that it was integral to the plot and the theme of the series. It was not some casual music number inserted to draw in fans of the –back then- growing genre.

“In this series, everything I was passionate about came true. I researched the YouTube persona Zalata and wrote a role specifically for him to play, there were also notable roles for the Lebanese megastar Nadine Rassi and a guest actor from Georgia; Mr. Leo, well-renowned in his home country. We paid him $1500 a day, which was his charge, since foreign actors require different payment strategies than ours [in Egypt]. His professionalism was a sight for the sore eyes as he worked with us 11 days, 4 hours of shooting.”

Despite all the elements of success, Hole of a Needle was a sleeper hit. It did not boom in Ramadan because a single network owned the exclusive rights to air it, which in turn decreased the number of viewers,”

After Hole of a Needle, Fakhr decided to focus on his passion project; the one he prepared specifically for Mohamed Ramadan; a low budget series titled Ibn Halal – Goodfella.

The series that establishes Mohamed Ramadan’s start persona “Ibn Halal”

Ibn Halal was a political drama as far as political dramas could blend action, emotionally charged storylines and a horrifying tale of power abuse and sexual obsession.

“The project was titled El sekaa el e’wga – The Dark Side. It was different back then, people did not believe in Ramadan’s capabilities as an actor, as well as a bankable TV star. He was not that famous in 2014. I wanted to take him out of his comfort zone and give him a different kind of heroism than he was used to,”

Ramadan has only been playing thugs and rogues who go astray with no motif or a well-defined character arc or development. In Ibn Halal he was treading unfamiliar territory, one that does not comply with his brand persona; or the image that he supposedly was beginning to build as a star.

“Throughout the reading sessions, Ramadan hated the first version of the script. He did not want to portray an imbecilic character, but more of a naïve hero. His experimentation had its limits, and I attribute that to his star image which he was afraid would be shaken if he completely shed off the skin of the gangster/strong guy subject to injustice. He did not have a history so he could not gamble a future with a possible wide target audience of TV viewers.”

Not only has Fakhr been always rooting for the underdogs in his works, he was rooting for himself. He took the stairway to popularity and respect as a director one at a time, preferring to stick to the characters he believed in most and the stories he was passionate about.

“My dream cast [in Ibn Halal] included Ahmed Hatem, Ahmed Fouad Selim, Hamza Eleili –of theater fame, playing a character onstage similar to Messakar who appeared in Ibn Halal. It was not originally in the script but I added it to showcase a different side of the main protagonist Hebesha.”

Despite the major success that Ibn Halal met, the environment was not that friendly for a TV series starring Mohamed Ramadan back in 2014.

Ibrahim Fakhr directing a key scene

“The production company was unsure of how audiences would receive it. The series was bloody, violent and daring. But I could not stray from what my fans expected of me. I did not want to lose my target audience so we were pressured by production to reduce the budget. It was a bit of a frustrating matter to me, Ibn Halal was their least costing series, yet it was sold to three major TV networks; MBC, Al-Nahar and Al-Hayat.”

Fakhr helped create the modern image and star persona of Mohamed Ramadan. The script was very well-written, every side character had a dramatic significance and a character arc, and the director polished every side character to fit a grander scheme that serves –ultimately, as is the case with most Egyptian films and series of the day- the star of the show. The main storyline is usually focused on the main protagonist, the star for whom the bell tolls and the money talks.

“Unfortunately feedback was only directed at the star [Ramadan], critics either praised his performance, ignoring the series as a whole, or slammed him. The idea of a series based on a true story drew criticism, and critics attributed the success only to the original source that it draws inspiration from. This is a problem that I believe persists in the Egyptian TV and movie platform. Either we glorify a star or we push them down to the gutter. I received most of the negative criticism.”

I was particularly surprised with the criticism directed at the series for using a real-life tragedy to build a work of art. Since when was this a drawback? Fakhr was just as incredulous,

“The Assassination of John F. Kennedy and Titanic were both major successes based on true stories, this does not mean they are anything short of great works of art.”

Back to Rasayel, Fakhr talked me through how he handled the script from the time he met writer Mohamed Solaiman Abdelmalek until it landed in the diva Mai Ezz Eldin’s lap.

Ibrahim Fakhr in Georgia while shooting Khorm Ebra

“I met Mohamed Solaiman Abdelmalek and he told me about his vision for the script. It was not that well-structured, then. But I became so passionate about it and delivered it myself to Mai who is a close friend of mine. She was pretty skeptical about taking up a role that would deviate from her regular target audience,”

Talking to Fakhr, it seems that he knows how to make a star shine, without shedding off the image that enhances their star power. With Mohamed Ramadan, he established the image of the good guy gone rogue without losing the Robin Hood-like justice. With Ahmed Hatem, he helped in creating the modern bad boy who escaped to the dark side. With Mai Ezz Eldin, her career path was handled by Fakhr from A2Z.

“When I met Mai, her most famous TV series to date was Girls Having Fun – Dala’ el banat where she played a low-class, vulgar girl. I guided her on how to target different social classes through her art, and from then a successful and fruitful work partnership was born. With The Case of Eshk – Halet E’shk, she found a way to attract middle-class TV viewers, playing an Upper Middle Class girl suffering from multiple personality disorder which resulted from a childhood trauma that she could not remember. Starting from this stage, her star status as a fashion icon was beginning to be implemented. The following year, Mai wanted to explore a love story, so I suggested Wa’ad which was in reality based my own past teenage love story, with a foreign woman whom I met on the Internet.

For a year and a half we chatted online, then she visited Egypt and we spent amazing time together. I thought we would eventually get married, then she uncovered the sad truth; she would never be able to live with me in Egypt.

The story ended and I used it for inspiration in making Wa’ad. I drew some details from my own experience; how I collected her fallen hair from the pillow after she left. The longing that the character Youssef – played by Ahmed El Saa’dany who starred alongside Mai- had for Wa’ad, and the details of the scene where she leaves him for the first time and he listens to I’m ready for Love. These are all inspired by my real-life experience. The realistic ending surmises my point of view on how that particular love story should have a conclusion.

Mai Ezz Eldin in Wa’ad, Fakhr’s most personal project to date

I believe that even remembering the pain of love creates beautiful memories. I walked the series with Mai step by step, starting from a storyboard and until the actual shooting. It was a tiring shoot. Too many locations, and in every location there would be more than one scene to be shot. But I loved this series, and I knew that it had to be done right or not done at all.”

Wa’ad introduced Ezz Eldin to a different target audience all-together, the A+ class TV fans. Through Rasayel, she could attract the attention of a class that she had not even tried to tackle; the intellectuals.

“The script for Rasayel had to be modified to match my directing style. I wanted to make it closer to people. Apart from the intellectuals, I wanted to broaden the target audience circle to include teenagers, housewives and mothers. I added some action sequences to draw the attention of teens. To include the average female viewer, script modifications had to be made in order to match my directing style and vision. Mohamed [Solaiman Abdelmalek] and I worked on the script, in order to make the characters more religious. I requested that Hala’s –the main protagonist- father get a background as an Arabic language teacher. I also wanted her sister to be less educated than her in order for a broader section of the public to sympathize with her. The script in its original format was too elite for the average Egyptian audience, which firmly believe in two things: religion and heritage. So I tried to tie the general theme of the series to Joseph –the prophet in the Islamic scripture- and his dream interpretation skills. I also made sure that every side character had a resala – message rather than simply Hala and Sameh. Mai was more interested in the commercial side of the series, while I was trying to find the link between Mohamed [Solaiman’s] script and her star image. Throughout the series, I used dynamic shots excessively, which Mohamed loved while Mai hated.”

Ibrahim Fakhr with his longtime collaborator actress Mai Ezz Eldin

Fakhr has a deep understanding of the average Egyptian TV viewer. He knows how to target specific audience groups and demographics according to their needs and tastes. He remembers every small detail and pays careful attention to every shot.

“In my work, every shot should have a significance in the grander picture. You also have to be specific with the type of shot and the camera angle, a long shot cannot be a close-up. In Rasayel most of Hala’s solo shots had to be top ones –the Eye of God shot- so that it resonates with the sufism of her character. In Ibn Halal I always shot Ahmed [Hatem] –who played the titular villain- from a low angle to make him imposing and scary, every time he appeared onscreen the audience would feel a little off, like something was not right. The iconic object of his obsession, Yosr, played in the series by one of the hottest actresses at the time Sarah Salama, had to wear extravagant makeup and clothing to appear sexier than her already beautiful fellow actresses. But one problem faced me; I am conservative and I did not want to sexualize the actress, but the character herself. So I made her iconic through showing her from a wide angle. She looked tiny in the shot so that the focus was not on her body; but viewers could also see that she’s dressed in a sexy way. The scene would remain in wide-angle for 10 seconds, then I would cut to a close-up on her innocent face.”

On directing actors, Fakhr gave a hint from one of his favorite scenes in Ibn Halal,

“What has always helped me as a director is that I have been an actor before, only abandoning it because I seek truth of movement, and only through directing do I achieve that. When I shoot the scene, I try to see it from the actor’s perspective as well as the director’s. I seek great composition while maintaining a dynamic scene, with people constantly moving like it happens in real life, as opposed to how most scenes are shot within the medium of television.

In the scene where Hebesha kills his sister to avenge for his honor, Mohamed [Ramadan] was anxious as he did not know how to work it out through movement. So I guided him through the scene; he would place his sister’s corpse on the bed then he would try to sit down, stand up then move back and forth. His movement mirrors his internal monologue;

How can I sit down? Where do I sit down?”

This year, Ibrahim Fakhr did not stop with the controversies. His collaboration with Mohamed Ramadan resulted in Zelzal – Earthquake a drama about his favorite social class, those living on the margins of society, the clash between neighboring social circles and doomed love stories.

Ibrahim Fakhr with Khorm Ebra crew

What does he have to say about the series?

“I was offered the chance to direct Zelzal this [Ramadan] season. I was not a huge fan of the script, since it was too mushy for Mohamed Ramadan’s persona. People are used to seeing Mohamed’s character with melodrama, fighting and wreaking chaos. This was more of a drama for the middle-class families gathering around the TV, in other words, not suitable for Ramadan’s target audience. Since the production company insisted on using this script for Mohamed, I decided to play it with my own rules. I took the risk and added spices to the script so that people become more interested. I asked myself;

If not for the action and thrill factor, how do we get people more interested in Mohamed Ramadan?

So I decided to use two elements; nostalgia and agricultural laborers. Nostalgia was an integral factor for Generation Y of 1990s fame, and it was not explored before, which is why I tried to adapt my own voice as a 90s kid and even gave the titular character in Zelzal the same birthday as mine. This gave the character a personal aspect through which I could reflect on my own childhood and teenagehood. I inserted all the details from the nineties; the Walkman, cassette tapes, the creative advertising, the 90s crew cut (kaborya), etc.

In terms of the agricultural laborers, I added certain details from their lives which most people are not aware of such as how laborers go back and forth from their hometown to Cairo and where they usually meet in their pastime. I used interactions between characters to create different dynamics from what people are used to in Cairo such as how the village schoolteacher has a close relationship with the whole family of the student and how that affects inter-character relationships. I come from an agricultural laborer family, from Shibin Al-Qanater city in Qalyubia Governorate. So I knew exactly what I was talking about; what I was researching.”

I was so taken by Fakhr’s vision and attention to detail, that I wondered what he might envision for a more successful future;

“Cinema is my ultimate goal and dream. I wish I could make a successful film career similar to my TV career. All my life I have envisioned the premiere of my debut film, to watch people’s reactions to my film; how they laugh and cry and interact with the actors on the big screen. I try to capture the feeling with the pilot episodes of every series that I direct. I invite my friends over for a private screening of the pilot and watch their reactions. Finally I have the chance to reciprocate that feeling on the big screen.

Actually I am currently offered the opportunity to direct an important action film, with an amazing cast which has been my dream, with a release date –hopefully- by Eid Al-Adha in August.”

A dreamer, a tactical professional and a rebel of sorts, watch out for Ibrahim Fakhr, who –despite what anyone might think of his art- never fails to dazzle, surprise and provoke.