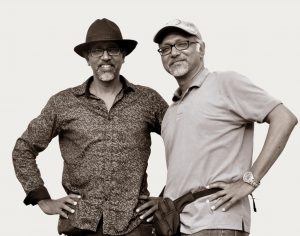

Satish and Santosh Babusenan

A Journey through Bodies, Souls and Time

During the 38th edition of Cairo International Film Festival in 2016, I had the pleasure of watching an unconventional Indian film. Prejudices aside, for me Indian cinema represented Bollywood, which is an overabundance of melodrama, dancing and dreamy looking Indians who –I am sure- had nothing to do with how real life Indians looked like. It came as a surprise for me to discover brother directing duo Satish and Santosh Babusenan’s film “The Narrow Path – Ottayaal Patha” which was a sensual masterpiece, with minimal lighting and a camera that keeps rolling to allow the characters to evolve in front of the audiences’ mesmerized eyes. A meditative look on life, death, desire and familial conflicts; “The Narrow Path” was a testosterone-infused film oozing with the sensationalism that only sensitive artists could capture.

Satish Babusenan and Santosh Babusenan; who are they?

Two Indian dreamers who abandoned the materialistic, commercial, fast-paced world of MTV India where they worked as music video directors and returned to Kerala; their hometown where they explored their artistic ventures through their movies. Since then they have mutually agreed not to promote their works unless a curious 30-year-old feminist critic decided to do that on their behalf.

“The Narrow Path” was the Babusenan Brothers’ second feature. So I went and sought their debut feature “The Painted House – Chaayam Poosiya Veedu” which director Santosh informed me had faced problems with The Central Board of Film Certification (CBFC) in India due to nude scenes which the board asked them to “blur”. As ridiculous as that sounds, the brothers Babusenan stood their ground against censorship on their artistic liberty. The nude scenes remained untouched. Nudity in their film was key point in the plot; where the old Gautam is being taunted by the naked Vishaya’s beauty; nothing exaggerated or over exemplified. Just a simple stance, a gesture in time. In their words, the nude scenes was a cry against identifying with the mainstream psychological facade and full awareness (and acceptance) of inner nature as a necessity for liberation. Morality – which varies from society to society- glosses over the individual self-image.

(Still from “The Painted House – Chaayam Poosiya Veedu” featuring Indian actors Neha Mahajan and K. Kaladharan)

In “The Painted House”, Gautam is a writer who undergoes a spiritual awakening of sorts after an encounter with a beautiful woman and her ruthless boyfriend. His sense of self and creativity are put to a test. His obsession with himself as a creative individual traps him within a safe, confined world of his own making. His bubble of false safety is ruptured after he meets Vishaya and the violent Rahul, through which he flips from promise to threat of a grander life, one where his idealist creative shelter is challenged.

“Gautam, the saintly looking, is a ‘nice’ human being [who] needed to question his ideas about sexuality if he had to find himself. Thus; we needed him to see Vishaya (a name which means ‘subject’) in her nakedness. She even consoles him by saying that there is nothing wrong in seeing a woman naked, perhaps suggesting that if anything is wrong, it would only be in his denial of his response to it. Even before we wrote that scene, we had decided that we would have trouble with the Indian Censor Board.”

The Babusenan Brothers grew up in an environment where senior Indian filmmakers resorted to the comfort of their inability to depict nudity on the big screen. Being the rebellious, liberated-from-commercialism filmmakers that they are, they decided not to wait for freedom of expression to be handed directly to them. They went ahead and showed the character [Vishaya] naked without considering the censors’ approval or rejection. Their fighting spirit and solid philosophy allowed me to ask them the burning question; how did they take a non-sexualized, non-normative approach to female nudity onscreen?

“We do not believe nakedness is sexual; only a person’s response to it is. Our actor Neha Mahajan who played Vishaya shared our commitment to our art and so she was very comfortable when we shot those scenes. You might have noticed that we never used the nudes to promote our film!”

The Babusenan Brothers share an unflinchingly advanced stance that opposes how female nudity is generally treated in the Western film word. In an article titled “A Matter of Legitimacy: Female Nudity On-screen” Kristen Lopez explores the multitude of methods in which misogyny demands that female nudity should be a screen necessity as well as a marketing tool for films in which these scenes are not a key plot point or theme. This contradicts how the female nudity is represented in “The Painted House”.

I had my own interpretation of “The Painted House”, however, the Babusenan Brothers had their own perception of how the narrative unfolded symbolically;

“The boy in “The Painted House” is ‘meant’ to represent the aggression the writer has kept bottled inside quite unbeknown to him. And the girl is the sexuality he thought he had outgrown.”

The Babusenan Brothers are minimalists when it comes to their filmmaking elements. Unlike the theatrical music that traditional Indian films use, they rely mainly on natural sound; water drops, wind caressing leaves, car horns and loud motor noises in a traffic.

Their third feature “Lost – Maravi” revolves –in their own words– about how individuals tackle guilt or how guilt tackles them; with strong performances from K. Kaladharan Nair and Nina Chakraborty.

The Babusenan Brothers value time, their films contain long shots where the camera stands still taking full advantage of the lush surroundings. They also value realistic dialogue, they allow their actors liberty of free flowing dialogue which brings the medium into the school of realism as close as possible.

In their corner of the world the Babusenan Brothers evoke inspiration through their surroundings whether the people or the environment, their art is highly personal yet it transcends through different cultures due to the themes that it digs through.

In “The Narrow Path” father-son dysfunctional dynamics are at the heart of the film, “Lost” is more about coping with guilt and the repercussions of owning up to your actions. There is no Bollywood propaganda; no sultry actresses with extraordinary beauty. No young, hot dancing Indian gods who can kickbox as efficiently as their disco moves. The Babusenan Brothers are the anti-Bollywood movement we have all been craving. Watching real-life Indians grapple with guilt, lust and grief without the ominous soundtracks and the splendid costumes is a sight for the sore, art-seeking eye.

(Still from “Sunetra – The Pretty Eyed Girl” featuring Indian actors Sreeram Mohan and Nina Chakraborty)

The Babusenan Brothers do not seek their ideas, they simply wait for ideas to simmer;

“Normally we just wait around till an idea strikes us and then we get cracking on it. Try to develop it into a story. A lot of such ideas get thrown out by one or the other of us even before it can get to the story stage.”

There is no dictatorship under the Babusenan roof, both brothers have veto power to throw an idea away in case they found it…

“…too trite or overdone!”

Seems strange for a directing duo whose life is technically spent contemplating grander themes and trying to fit them around the same actors all over again. You might think they rarely get bored. In each of their films they chase subtlety;

“There’s also this thing about our themes. We usually work on themes that relate to psychological or philosophical questions. Our films are basically about how one should live here.”

Their films personalize their struggles with a world that they have been trying to solve as if it were a mystery. On their official website their filmmaking philosophy is described as: “how belief in psychological and ethical certainties complicates life and how ´letting go´ brings freedom.”

Talking to them, you would think their lives –conjoined in a mysterious and overwhelming way– were journeys spent trying to decipher some of life’s abominable codes;

“We were trying to solve some of these questions ourselves. It’s an ongoing investigation of these questions. Why are we miserable? Why are we happy? Do we have a say in the events that happen around us and to us?”

All three movies subconsciously lead to one another; like an elongated, visceral chain where the same people get to play dress up, undress then reenact their past, present or future lives. The Babusenan Brothers’ films showcase the spirit of reincarnation in the sense of how a group of similarly looking people are reborn each time into a different life. In “The Narrow Path” K. Kaladharan Nair is a bed-ridden grumpy old man, while in “The Painted House” he is a writer suffering an enlightening heart attack where he goes into a rites-of-passage-like coma and in their latest creation “Sunetra – The Pretty Eyed Girl” Kaladharan plays a criminal on the lookout for the lovers who stole his car.

Films with the Babusenan signature though different seem really connected. A true recognition and implication of how personal art exists. Their dialogue is philosophical, contemplative filled with reminiscence on the nature of the human spirit, life, and death.

When asked about their technique, the Babusenan Brothers referred to the obvious;

“We don’t make story boards, but we do extensive rehearsals on location. It’s almost like having a story board! Once we have come to a broad agreement on a scene, one of us sits in front of the computer and sees the entire scene come up alive in front of him it is almost as if we can hear and see clearly; the characters, the expressions, the costumes and lastly, the words.”

This does not come off as a surprise. Keen in their professionalism, you can notice how their films unravel through unified sets and settings. What strikes as frivolous and full of life is their choice of actors; which they view as a diverse platform for stirring conflict due to working with actors from different ages and attitudes.

Characters go through crises in and out of aging stages; the veteran writer in “The Painted House”, the young son in “The Narrow Path” and the young girl/lover in “Lost”. Characters introspectively analyze their inner and external surroundings through posing questions that -most of the time- remain unanswered.

“Lost” could be their most external work of art. Outdoor locations are prevalent, with extended long shots of the beautiful Indian landscape. Is there a reason for that?

“We’ve tried to pack the film with metaphors of hidden things oozing/emerging out in unsuspecting ways. The bubbles in the drink, the tree springing out of the rock, the snails emerging from the pot, and several others. We were trying to use these as rhetorical devices while trying to keep them as subtle as possible.”

Subtlety is out of the question. “Sunetra – The Pretty Eyed Girl” gives an insight into two polar opposing worlds; the world of dreamers, two lovers with different ethical views on life and two criminals who have lived the life as it is and took it for what it threw at them from hardships and mishaps.

Whether a moral dilemma or a social commentary, The Babusenan Brothers reached a point in their artistic ventures by questioning their beliefs and liberating themselves from egregiously false dichotomies such as right and wrong, good and bad, knowledge and ignorance. Their future is laid ahead of them; they plan on their fifth long feature by commenting on the rise of right-wing conservatism in India and the challenges that liberals and communists face through the story of an activist writer who meets a female researcher writing a book on the few voices fighting intolerance in the modern Indian society.

Low-key and humble about their creativity, Satish Babusenan and Santosh Babusenan use the personal to drive the universal forward into the souls of their fans. They do not intentionally aim at reaching a bigger portion of the world, but on a subconscious level, their films stay poignant and resilient in the hearts of those who had seen them.