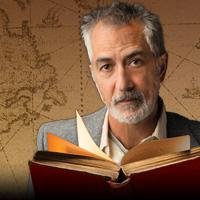

David Strathairn in Underneath the Lintel

UNDER THE SUBLIME

Underneath the Lintel

A play by Glen Berger

Starring David Strathairn

Directed by Carey Perloff

American Conservatory Theater

A review by Christopher Bernard

Underneath the Lintel, the one-man play by Glen Berger that is receiving its first ACT production in San Francisco this fall, is a detective story of sorts, though the victim of the crime is not exactly dead – indeed, he is, or at least seems to be, anything but, and the crime is not murder, at least not of the usual sort, though what the victim is a victim of, is certainly most foul. There is even some question whether the crime’s perpetrator even exists.

Nevertheless, the play’s sole performer is most insistent that, if this particular victim exists, the criminal must exist also, and one finds oneself in the end agreeing with him, even excitedly so- if there is this victim, then there must be this criminal. And for reasons that will become clear, many of us will in fact want, even hope for, this very criminal’s existence. So in order to find the criminal, we must first find the victim. And that is where the story begins. Does the victim exist? And if not, where do all those drops of blood lead? To underneath a certain lintel?

(A lintel is a piece of wood (usually) that forms the top of a doorway or window, so “underneath a lintel” is the equivalent of standing in a doorway or leaning out a window. More about this later.)

But, before I continue, let me get some necessary housekeeping out of the way. First, this is one of the most completely successful productions at ACT that I have seen in years. There is an unusually strong balance of acting, producing, directing and scriptwriting that I don’t often find in local theater. The direction is discreet and focused; the acting is skillful, honest and selfless; the set is ingenious but not self-conscious, a back wall cluttered with paraphernalia from productions past, the sort of stuff you would expect to find in a small-town lecture hall, complete with carousel projector and little pull down screen, and the kind of bulky stairs-on-wheels you’d stumble over in a large, public library. And the play offers that blend of entertainment and enigma, puzzlement and illumination, strong feeling, deep thoughtfulness and humane comedy – philosophical in the original sense of the all-involving, all-tormenting, all-hopeful, and sometimes entirely ridiculous, search for truth that is the soul of all great love affairs – that theater, in the wealth of its humanity, can provide more effectively than any other medium.

A graying, slightly befuddled, one-time librarian from Poland (played with the deftest of touches by David Strathairn) walks onstage to give, “for one afternoon only,” a talk – or rather, as the play is subtitled, “An Impressive Presentation of Lovely Evidences,” as he says in his slightly tarnished English. He opens a battered suitcase, in which he says he has collected “scraps” of a life, “evidences” that he hopes will “prove a life, and justify another,” namely, his own.

One day, in 1986, as the librarian was cataloguing books returned through the overnight book-return slot at the library of the small city in Poland where he has lived and worked all his life, one of the books – a much thumbed and annotated Baedeker – had been checked out, according to the last stamp on the inside book slip, 113 years before. The librarian is, naturally, dumbfounded, though also, like the small town functionary he is, indignant and his bureaucratic prowess being put to the test, decides to track down the offender and extract the fine the library, in all its dignity, is due. This, unwittingly for him, leads eventually to a worldwide search – from London to Bonn to Beijing, from New York to Sydney – in a tantalizing quest for the elusive borrower of the spectacularly belated volume; a quest that will cost him his job, his friends, his country, perhaps even his sanity, and may prove to be never-ending, even futile.

At each station of his progress, if that is what one can call it, he picks up a piece of the puzzle, a rag-end of “evidence” of the existence of the borrower, a person he grows to believe is none other than the mythical . . .

One cannot really discuss this play in any detail without being in danger of revealing too much – and yet, if one reveals nothing, one is left without the pleasure of demonstrating to the reader just how deep this artful, profoundly thoughtful and deeply felt play eventually goes, far more than one could possibly have guessed from the frayed bits of evidence and hardly sublimely promising opening – and yet sublime it becomes. So, if the presentation here stutters now and again, withdraws, shies coyly and bids fair to be just a bit too oblique, the writer can only plead extenuating circumstances and, if anything, a great, even perhaps too great, respect for author and players and public. But here we go anyway.

We’ll let it sit at “mythical,” shall we, and let the implications unfold in all their many, searching, reaching, even over-reaching and, yes, tantalizing directions. But I can’t drop it entirely without mentioning that it has something to do with an incident, perhaps apocryphal, during the passion of Jesus of Nazareth, as he dragged his cross among the Roman soldiers through the alleys of Jerusalem on the way to Golgotha, past the homes and shops of the locals, few of whom had any idea who this person might be – just one more troublemaker on his way to what was probably a well-deserved end – when the poor fellow dropped his cross, to rest briefly before the door of a cobbler, where the cobbler was taking a brief break from his labors under his lintel, and, frightened by the looks of the soldiers, the crowd, the other criminals on their way to execution, and the bloody face staring up at him under a nasty looking crown of thorns, the cobbler told the fellow to shove off, get off his stoop, and keep going, and Jesus said he would do so, but the man would have to tarry here until he came again. And, according to the story, the man did tarry, and is still tarrying, until the second coming, or forever: the Wandering Jew, the victim of the one certain “criminal,” God.

____

Christopher Bernard is a poet, novelist, essayist, photographer and filmmaker living in San Francisco. He is author of the novel A Spy in the Ruins and the recent collection, The Rose Shipwreck: Poems and Photographs. He is also co-editor of the webzine Caveat Lector.