What Are We, Anyway?

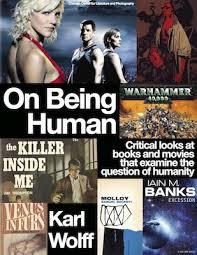

On Being Human

By Karl Wolff

38 pages

Chicago Center for Information and Photography

Various formats, including electronic and a paper edition, available at cclapcenter.com/onbeinghuman

An essay review by Christopher Bernard

The question “what does it mean to be human?” has become daunting. Both more urgent and more problematic in recent decades, it promises to become even more so in years to come. This short book of brief and stimulating essays on “novels and movies that examine the question of humanity,” written by Karl Wolff, a staff writer and associate editor for the Chicago Center for Literature and Photography, brings a number of these concerns to sharp focus. His book does what criticism does at its best: not only raising important questions and suggesting new avenues of exploration but introducing readers to ideas and works new to them, or encouraging readers to revisit and understand them in new ways.

It is odd that up until a few decades ago, the title “On Being Human” could have been used for some anodyne book in an undergraduate “humanities” course on “the miracle of Greece,” the marvels of the Renaissance, and the triumph of the Enlightenment, with a few passing references to such modern sages as Tolstoy, Albert Schweitzer, and Gandhi. Only in the last century, especially the last generation, has the category “human” become problematic, troubling, even empty, as the lessons of the “inhumanity” of human beings learned from the monstrosities of slavery to the carnage of Verdun to the death camps and killing fields of Europe and Asia to the Sixth Extinction have sunk in, and the virtues of our humanity have seemed increasingly overwhelmed by our evils.

A related, only apparently less dramatic, problem is that human beings do not have a consistent idea of what “being human” means; defining “human” is a cultural act, not a biological one, so that it becomes possible for a human being to relate to, even to identify with, a being that is not biologically human at all: an animal, an abstraction, a machine, a god – and to deny humanity, despite all appearances to the contrary, to a member of the same species (Nazis considered Jews, American slave owners considered blacks, and war enemies are often culturally encoded, to be “nonhuman” despite appearances – as though a human body were no more than a cloak of deception hiding an essence that makes one “really” human). As “differently sentient” beings (a term used in Battlestar Galactica, a TV series discussed by Wolff) come into existence in the years to come, Wolff notes that we’ll have to deal with this profoundly human but appallingly slippery question of definition.

Not least, “being human” has both descriptive and normative meanings: when we say, “be human,” we don’t usually mean “be like Idi Amin at his worst,” even though Idi Amin was not, technically speaking, either less or more human than, say, Mother Teresa or Pope Francis.

Wolff’s book, brief as it is, is a welcome addition to the literature on the topic of what it means to be human in a potentially posthuman age, and it has introduced this reviewer to a number of works I’m now curious to look into, which I will discuss later. First, a little background.

For millennia, western civilization has placed “man” at the center of the world; both the Graeco-Roman and Judeo-Christian worldviews have this curious fact in common (the male at dead center, the female just off to the side). This is unlike the rest of the world’s cultural traditions, which tend to place human beings somewhere at the periphery of a cosmos dominated by nature or the gods. Western religions (which have been, and still are for many, the heart of western civilization), despite all of their bellicose deities, place human beings at the center of meaning and grace. There is certainly no more human a God than Yahweh, who has an obsession with human beings that can sometimes seem unbalanced; the God of Christianity actually became a man (which strongly suggests that man is, and always has been, potentially godlike); and the God of Islam speaks exclusively through one man, the prophet Muhammad. In all three cases, the universe turns on the relationship between God and humankind – and this relationship puts humankind and God on a common level, almost “equating” the divine and the human. The religions of the Book act as though the entire universe is arrayed around the behavior of humanity, awaiting its fate and judgment as though its own existence depended on it. And, according to the Book, it does.

In curious parallel to Western religion, the Greeks and Romans, and the culture and civilization they bequeathed to us, laid the framework for the secular humanism that dominates much of the west, indeed of the world, today: some might even say that modern liberal humanism is a suit of Judeo-Christian moral values uneasily riding various sets of Greco-Roman metaphysics, from the “spiritualism” of Plato and Plotinus through Aristotle to the Epicurean materialism of Democritus and Lucretius.

However, unfortunately for the post-enlightenment project, of which liberalism of both left (“San Francisco values”) and right (neo-liberal capitalism) are the latest heirs, the last three centuries have seen a slow, then rapid, peeling away of the various metaphysical assumptions of both the Judeo-Christian and Graeco-Roman heritages until, at this point, there seems to be nothing left to recognize as “real” except, on the one hand, the fantasies of language or, on the other, matter and energy – or, to put the matter bluntly: delusions, money, and power. To make matters worse, there also seems to be no metaphysical, let alone religious or spiritual, distinction between humanity and the rest of the universe. Liberalism, which still wants, with some desperation, to believe in its own traditional values of tolerance, moral progress, the value of the individual, the expunging of suffering, and so on (essentially religious values, though without a metaphysics that could support them) or to see humanity as having an ultimate, and absolute, value; in a word, as “sacred” – is trying to expand its values to include the entire cosmos. And that is a beautiful and noble idea. But there is one fatal problem.

Liberalism also believes that the only acceptable intellectual tools are reason and experience. Two possible paths follow from this commitment. One of these paths is science. Science, however, demonstrates a world in which nothing is “sacred,” including human beings; a world that has no intrinsic value, no value even in reason or experience, no value even in science, because the scientific method – from reproducible experimental results to mathematics to technological fixes to pragmatically defined problems – can find no rational basis for actually valuing anything, including science. Reason and materialism cannot justify themselves or anything else, including human beings or so-called human valuesThe sciences cannot, by their very nature, provide any basis for values, including the values that support them.

For example, Darwinism may in fact be true (all of the evidence so far strongly suggests this), but it rips the heart out of human values of any kind. Darwin himself was a racist (hardly unusual for his time and place) and had no compunctions supporting what we would call “genocide” today. It was just another form of natural selection as far as he was concerned. Reason, materialism, and science are destroying even the identity of human beings: we no longer have any idea what a human being is, except in so far as what human beings in fact do – and that, when seen in the aggregate, is not very inspiring. How many Mozarts, Shakespeares, Einsteins, or Van Goghs does it take to somehow make up for a single Stalin or Hitler or Mao, each of whom murdered millions of people, or the average middle class human with a car, because of whom one species in the tropics (it has been estimated) may be going extinct every 100 minutes?

The other path from the commitment to reason and experience (begun by Nietzsche but taking a century to work out its full implications) leads to extreme nominalism, or the belief that only individual experience is ultimately real, which leads to postmodernism and poststructuralism, which have been a nearly suicidal attempt to defeat reason and materialism (in a word, science) on their own ground. But that idea for a cure is worse than the disease, if that were possible. The insanity of reason is countered by plain old insanity; thanks to the good graces of postmodernists and poststructuralists, the ongoing nihilism of the liberal project has been advanced to where we no longer know where we are; we are invited to “be mature” and accept our despair and try to enjoy it while we still can (thank you very much, Dr. Freud). We ask for bread – we in fact need bread to survive – and we are offered stones, and told to get used to it; grow harder teeth and stronger stomachs: “adapt, or die,” as one hardy nerd put it during the dot-com boom in the late ’90s (his startup perished a few months later). Who needs meaning, value, or hope when you have the internet and an infinite echo chamber for your fantasies (liberalism’s left wing) and an expanding free economy (liberalism’s right wing), which together are leading, first to intellectual and spiritual suicide (integrity despises illusions, and reality is never kind to them) and then to real suicide from our waste products, which the natural environment can no longer absorb?

So, what does it mean to be human? Wolff’s essays are brief but telling, each one containing a description of how the subject work (spoiler-proofed in most cases) approaches that question.

He opens with an analysis of the BBC series, titled, with obliging appropriateness, Being Human, about a vampire, a werewolf and the ghost of a murdered woman “living” together and trying to “pass” as human in British society, thus raising pertinent questions about what that would take. Other intriguing works Wolff examines in enlightening ways include Storm Constantine’s fantasy series Wraeththu, the popular leftist future fantasy “Culture” novels of the late Scottish writer Iain M. Banks, and Katharine Burdekin’s alternative history of the Nazis, Swastika Night (a presciently conceived novel, written in the 1930s, that describes a future in which the Nazis successfully take over Europe), and the hugely successful Hellboy comic series.

Wolff also writes perceptively about Maureen McHugh’s story about humanity’s less likable trait of pleasuring in domination, Nekropolis, and Leopold Sacher-Masoch’s primal S&M text Venus in Furs, which explores, or rather celebrates, the opposite trait. He then examines Jim Thompson’s dark The Killer Inside Me, Anthony Burgess’s even darker The Wanting Seed, and, perhaps darkest of all, the “deconstruction” of humanity to be found in the three early novels of Samuel Beckett: Molloy, Malone, and The Unnameable, novels Wolff calls “science fiction,” though more of the speculative than the “green men and spaceships” kind. (This is in truth not a new take on Beckett’s writing; Martin Esslin, a colleague of Beckett’s and a writer on his work, talked about Beckett’s work as a variant of science fiction in my hearing a couple of decades ago.)

Speaking of sci-fi, Wolff also writes about the American TV series Battlestar Galactica (the 2004−2009 version) and Caprica, the movies The Man Who Fell to Earth and The Dark Crystal, and the futuristic role-playing game Warhammer 40,000. He also explores the book-length, illustrated thought experiments by Dougal Dixon, including Man After Man, which looks into the possible evolution of humanity over the next five million years – assuming we survive the next century or two, which some thinkers believe is increasingly unlikely.

Brevity is no enemy of profundity, as the great aphorists and “blinkists” like Malcolm Glackwell can attest, but Wolff sometimes just scratches the surface of his topic in these essays, most of which seem to have been intended for the attention-challenged reader of the internet. I hope he will expand and elaborate on this topic in future studies. But he still gives the reader a lot to think about as we race toward the (liberating? the disastrous? the phantom?) “Singularity.”

For example: what will happen when “humans” become entirely assimilated to machines – and machines to humanity? What will “humanity” mean? Will it go the way of “divine” and “sacred”? Will Nietzsche turn out to have been right – was the death of God also the death of humanity? And to bring back human beings, value, worth, even the good itself – will we have to resurrect some sort of deity after all? After all, Nietzsche is dead. Freud is dead. Darwin is dead. The philosophes of the enlightenment are dead. Maybe it is time to give the poor men, after all they have been through, and after all they have put us through, decent burials.

[Edited version: 4/3/2014. The original version had two errors in it: “Battlestar Galactica” was misspelled, and “(the ’90s version)” should have been “(the 2004−2009 version).”]

____

Christopher Bernard is a poet, novelist, essayist, photographer and filmmaker living in San Francisco. He is author of the novel A Spy in the Ruins, the recent collection, The Rose Shipwreck: Poems and Photographs, and the story collection In the American Night. He is also co-editor of the webzine Caveat Lector.

Wonderful review. Karl and I know each other only as writers

through cyberspace. He did reviews for both my books.

I look forward to many more books, articles and reviews

from such a big thinker…Mary Kennedy Eastham, MA, MFA

Author – The Shadow of A Dog I Can’t Forget &

Squinting Over Water – Stories