OF DREADFUL CONSEQUENCE

The Rime of the Ancient Mariner

Word for Word Performing Arts Company

And Z Space

San Francisco

A review by Christopher Bernard

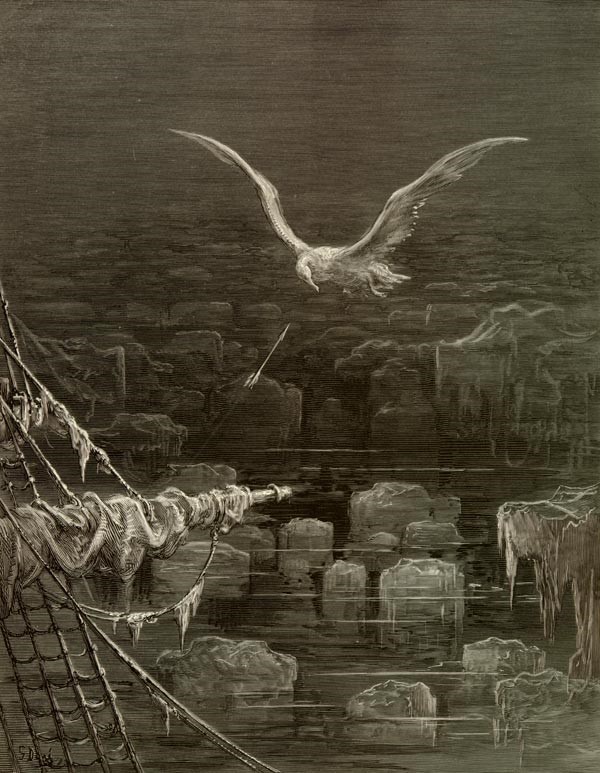

“ ‘God save thee, ancient Mariner!

From the fiends that plague thee thus!

Why look’st thou so?’ With my crossbow,

I shot the ALBATROSS.”

The new theatrical adaptation of Coleridge’s haunting poem by San Francisco’s Word for Word and Z Space could hardly be more timely. It opened on the day of the mass global Climate Strike of September 20; some in the audience still carried dust from local marches on their shoes.

The famous poem tells, in the form of an extended ballad, the tale of an old seaman who stops a young man on his way to a family wedding to tell him a story he is compelled to tell over and over again, of a mysterious and tragic voyage he made in his younger days south to the Antarctic wastes, where he shot and killed an albatross, despite the bird having led the ship back into open sea, thus sparing it wreck in frost and ice, and about the terrible punishments thereupon visited upon himself and the crew for this crime against nature.

Word for Word’s beautiful, sometimes harrowing, adaptation underscores the many prophetic aspects of the poem; not only for its, and our, terrifying future, but also those deeply rooted in our civilization: the humanism of the Greco-Roman world and the special creation of man and his role as master of nature claimed for him in the Old Testament; the humanism that has long defined Western civilization and that, turbocharged by the scientific revolution, the enlightenment, and the multiple industrial revolutions of the last two and a half centuries, has made us world-conquering and now world-destroying.

There is one question that anyone who has read “The Rime of the Ancient Mariner” has asked. The question has nagged for the more than two centuries since the poem first appeared. Students, teachers, critics, lay readers of all kinds ask: why on earth did he do it?

Why did the Ancient Mariner shoot the albatross?

It is not explained in the poem—indeed, the idea of motive is never raised. It seems an act of wanton thoughtlessness, boredom, whim. Yet, to a brutal fate, to avenging spirits and “a rotting sea,” to mass death and, for those who survive, a life worse than death, leads (in director Delia MacDougall’s memorable phrase) this “thoughtless act of dreadful consequence.” A seemingly random, unfortunate, but surely trivial deed has results beyond anything that seems morally or even practically explicable.

There is, perhaps, only one humanly understandable, if not respectable, reason. He did it, not because he thought that it was right or necessary, from superstition or fanatical zeal, or even from sheer malevolence—out of pride, cruelty; what we might call “malignant narcissism” or “toxic masculinity.” It was an act neither of misguided virtue nor of willful evil. He did it for one reason alone: because he could.

Our world of relentless disruption has come about for reasons not far different: the Mark Zuckerbergs, Steven Jobs’, Travis Kalanicks of the world have upended our existence time and again because they could. Some young man working in a midnight bedroom may yet find a way to blow up the world just because he discovers that, with this little thread of code populating every computer in the world with a single click of his mouse, he can.

Word for Word follows its customary method of dramatizing texts by presenting them literally “word for word”; in this instance, enacting the entire poem on a stage representing a minimalist skeleton of the Mariner’s ship, and flanked by sweeping ramps, like two arms embracing the vessel, that rise to a shrine-like alcove where figures of transcendence briefly appear—the “spirits” that inhabit the poem, including that of the albatross. The stage is a bit like a schematic image of a woman’s body, with head, arms, and womb: mother nature from which all things come and to which all things must in the end return.

Among the most notable performers of this evening were Lucas Brandt as both the Wedding Guest to whom the Ancient Mariner tells his inescapable tale, and the young mariner of the awful deed and spectral sea tragedy (most of the cast take double roles); a splendid Darryl V. Jones who takes the part of the Sun (who has indeed a defining role in the poem, as bringer equally of life and death) and also as the Hermit who shrives the mariner at the end of his long journey (Jones also wrote the idiomatic music for the Hermit’s song); and the lovely Leontyne Mbele-Mbong as a crew member and second of two disembodied spirit voices. Charles Shaw Robinson presented the Ancient Mariner with mournful authority.

The two directors, MacDougall and Jim Cave provide, in the program, particularly eloquent “director’s statements,” demonstrating an unexpectedly comprehensive understanding of Coleridge, who in later years became an influential philosopher some of whose ideas left traces on American transcendentalism, existentialism, and ecological philosophies. The directors, performers, and production team braid together their skills like good hemp cable to help the poet’s words, ideas, and warnings cross the generations to reach us with as much urgency as theatrical power.

It is well accepted that we are in the midst of destroying much of living nature that has thrived for tens of millions of years on planet earth, like the mariner’s shooting of the albatross, just because we can. Before our time no matter how much we were able to destroy each other, cities, cultures, entire civilizations, we could not, in effect, destroy everything. But now the world has become our toy; like many a child, we have been busy taking it apart to see how it works. And, like many a child, we are now crying because we don’t know how to put it back together again.

At the very beginning of this adaptation, in a brief prologue, the “spirits” that are as vital to the story as the benighted humans, and acting together as a benignant chorus made up of everyone except the tragic protagonists, present a short speech not to be found in the poem; it is repeated, word for word, at the poem’s conclusion. Who invented it? No one is saying. It is modest, kindly, ingenuous, and deeply moving, ending the performance on a note both questioning and hopeful. One can only be grateful, as we have never been more in need of hope.

_____

Christopher Bernard is co-editor of the webzine Caveat Lector. His novel Meditations on Love and Catastrophe at The Liars’ Café will appear in 2020; his third collection of poetry, The Socialist’s Garden of Verses, will also appear in 2020.

What a thoughtful, insightful review. Thank you so much. I just wanted to let you know that the “short speech” at the beginning and end of the show is another poem by Coleridge called “What If You Slept?”

What if you slept

And what if

In your sleep

You dreamed

And what if

In your dream

You went to heaven

And there plucked a strange and beautiful flower

And what if

When you awoke

You had that flower in you hand

Ah, what then

I’m so glad you enjoyed the show.

Best, JoAnne Winter, Co-Artistic Director, Word for Word

Dear JoAnne Winter,

Thank you very much!

Christopher Bernard

Christopher,

This of all your fine reviews deserves the highest praise. Especially with such keepers as “. . . and production team braid together their skills like good hemp cable to help the poet’s words, ideas, and warnings . . .” Your insight leads the psyche to believe that the seaman’s “duck hunt” was truly a singular event—with no others topping his crime against man, nature, and God before or since—making his act the Number 1 hit in the hit parade of humankind; becoming the quintessential artist, celebrity, power that be; with the only “next” and ultimate performer being he who pushes the bright red button . . . becoming the period, if not exclamation point, at the end of man’s most defining sentence.

Best, PJS