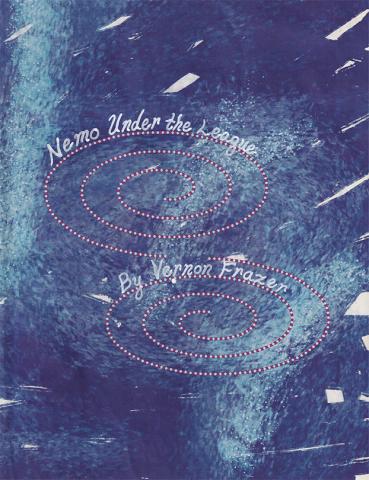

Vernon Frazer’s concrete poetry collection “Nemo Under the League” recalls Jules Verne’s underwater sea exploration journey in its title. Like Captain Nemo, Frazer’s poems probe lesser-explored and lesser-mapped areas: aesthetics and the subconscious. Black, white, and grey text, text boxes, lines and shapes appear on the page with the focus more on the aesthetic effect of each composition than on the literal meaning of the words.

The phrases and their arrangement on the page may seem random at first glance. However, there’s usually a directionality to pieces, such as “Blocking the Inevitable” which guides viewers’ eyes to the right, and “Reflection Locked in Reflection,” which follows a diagonal or elliptical path to suggest light bouncing off a mirror.

Sometimes the images evoke clip art, as in “Desire After the Elms,” or comic books, traffic lights, or even soup cans, as in “Career Moves.” Or even art deco motifs, as in “Birthing an Ungiven Given.” The text will occasionally relate to the title or presumed theme of the poem (such as “hordes of insufficient data” in “Finding a Reaction” and “overblown deduction guides tax the patience excessively” in “In Charge of What Follows”) but tangentially, creating the effect of a composition inspired by the idea rather than the linear development of a thought.

At times, while reading, I speculated on what colors and shades Frazer would choose had he decided to incorporate colors. Sometimes my mind suggested possible shades of deep blue, or vivid orange, or light green. The monochromatic feel works, though, to focus attention on the words themselves as the artwork rather than splashy colorful shapes.

In some pieces, “Flayed Nerve Endings Frayed” and “Reeling Toward the Reel” text itself forms into oval egg shapes or curlicues. Elsewhere, words appear in mirror images of themselves, vertically, diagonally, penetrated by arrows. Words become not just representatives of images or ideas, but as images and design implements themselves, while remaining readable.

The very last poem in Frazer’s collection, “The Transverse Clatter Balcony,” ends with text cascading down to the end of the lower right of the page. It reads “the last word … cast overboard … definition matter … soaked … in the lumbago sea with Carthage.” Words and meaning are not impermeable or permanent here, but forms of matter subject to the weathering of time, nature and history.

I recently came across Dr. Leonard Shlain’s The Alphabet Versus the Goddess: The Conflict Between Word and Image, in which the cultural anthropologist argues that the development of abstract, linear, alphabet-focused language rewired human brains and changed ancient societies. These changes brought about modern technologies but also fostered war, competition and hierarchy, religious extremism, legalism, and the subjugation of women and the natural world. As an author himself, Dr. Shlain advocates, not for the eradication of books and alphabets, but for greater balance between holistic, image-focused understanding and reductionist, linear ways of making meaning.

Vernon Frazer’s Nemo Under the League represents an effort at re-calibrating that societal balance by integrating words and images inextricably. It’s worth a read, or a perusal!

How do you match up the words you use to their backgrounds? Is there a pattern, or do you choose what feels right each time?

It seems different each time, but I probably work with several patterns that I’ve acquired from doing the work.

Even in these pieces, which involve composition, improvisation always plays a role at some point, directing me to choose what, basically, feels right at the time I’m writing it. During improvisational thinking, more elaborate plans do emerge: I can see a full page design or pattern of several pages at times.

What makes a word interesting to you? Sound, shape, length?

Sound is probably the foremost. Sometimes I feel like a jazz musician whose instrument is language. Generally, when I have difficulty finding the right phrase, I choose the one that sounds the most musical to my ears. It almost always turns out to be the best choice. Sometimes working with the shape of a letter or word leads to a phrase, a verse or a visual pattern.

Would you ever work in color? What inspired you to choose a black, white, and gray color scheme?

My equipment and the economics. My old color printer used an ink cartridge for every page I printed and the cost of printing a color book would make the sale price too high. Over the years, technology changed many things, as we all know. Ten or fifteen years ago, I talked about trying to do this work in color but my life didn’t make it a priority. When I joined the C22 Poetry Collective a few years ago, their aggressive experimentation led me to try it. So, I wrote a color book called SIGHTING I did that’s online, but not yet officially published. It’s officially coming out May 7.

When words occur to you, how do you decide whether to put them into a concrete poem or free verse?

More my mood in the moment, I’d say. When I feel I’m starting to stagnate, I’m more likely to do a concrete poem or a multimedia video to relieve my dissatisfaction. Those are the most demanding, after all. Sometimes I write textual poems because I don’t want to meet a more demanding challenge. Nothing is entirely easy, but some days I want to work in a different way, say, strictly with text and either a projective or left-margin pattern. Each method plays a role in my life.

Do you have any other writers or artists who have inspired or influenced you? Anyone whose work you find especially interesting?

I have many influences and hope I’ve made something of my own from all that I’ve learned. Jack Kerouac started me as a writer at 15. William Burroughs and Joseph Heller’s Catch-22 shaped my prose style. Until age 36, I aspired to be a novelist. But Charles Olson was an early influence at 15 and a major influence on my poetry until about 1988, when my style changed considerably. Peter Ganick introduced me to language and visual poetry. I absorbed many writers he published. My writing began to reflect the experimental work bassist Bertram Turetzky exposed me to in the mid-60s, when I studied bass with him. Peter’s publications revived those interests. Then, Steve McCaffery and bp Nichol influenced my work around 2002. I’ve read and absorbed many others; I was a literary omnivore.

Vernon Frazer’s Nemo Under the League is available here from the publisher.