Stand Clear of the Closing Doors

I walked briskly west to 40th and Sixth to catch the F train home to Queens, where I lived with my parents. It was already dark and cold even though it was only 4pm, early for me to be leaving the bank, where I had worked for six years, since I turned 24.

In the station, there were a lot of people on the platform. An empty train arrived, and I got a seat. Commuters hung over me, so I bent my head down to my paperback copy of Wuthering Heights. It had been my mom’s favorite book when she was a girl. I was midway through, engrossed in the story of Catherine and Heathcliff.

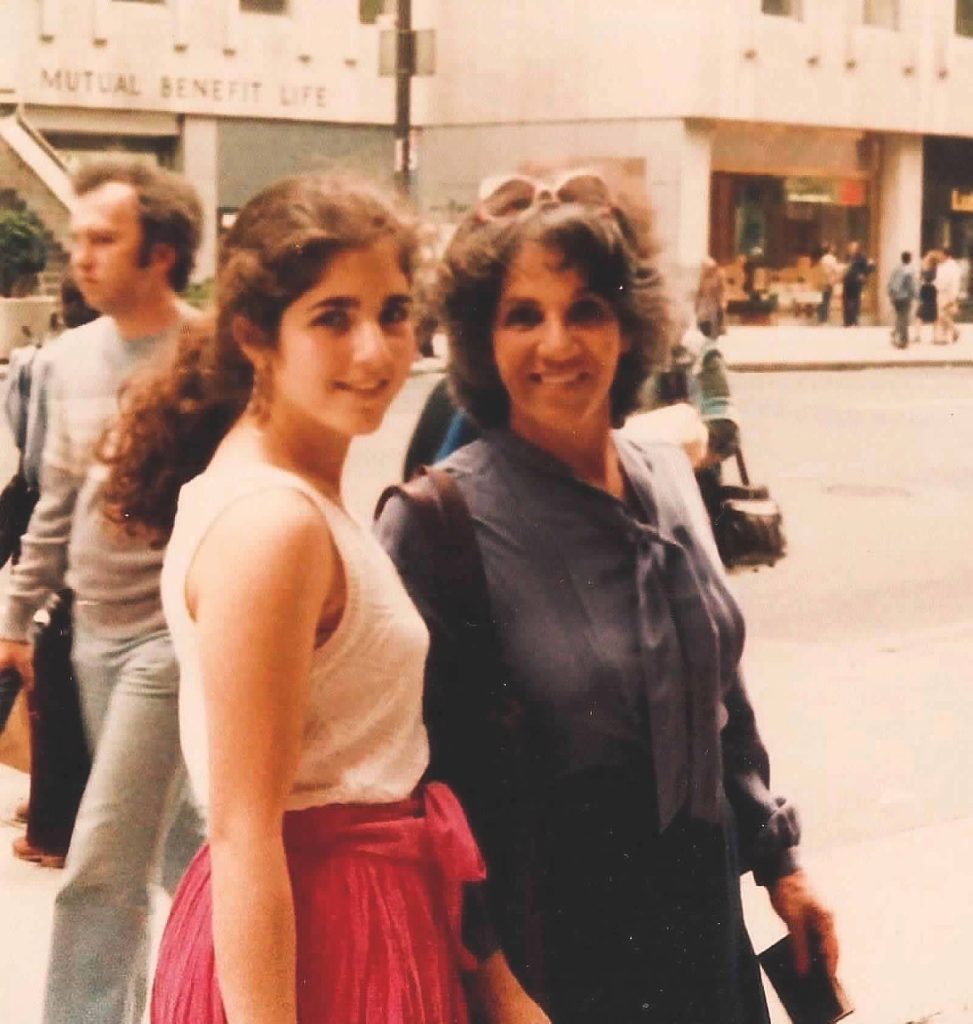

I loved imagining my mom young. It wasn’t difficult, even though I came late in her life. We had so many black-and-white pictures from her youth in Lebanon, where I could tell she had lots of friends and was clowning in almost every shot. In one she hung upside-down on a metal bar; in others she was skiing, swimming, and sticking out her tongue.

In junior high, I used to think that if somehow my mom and I were classmates, she wouldn’t choose me as a friend. I would run through every possible scenario where we might become friends and turn over in my bed with a sinking feeling that it could never happen.

In school I was bookish and had only one or two friends. We wondered how we could become like the popular girls, but it seemed out of our reach.

My mom was popular even at age 66. She had many friends. She oozed charm and wit. Maybe it was because she was my mother, but I saw her as the vibrant center of any gathering. I admired the magnetism in her.

The subway car screeched to a halt as someone stepped on my black ballet flat. I looked up. It was my mother.

She never took the subway anymore. When I was a teenager, she was nearly choked in the turnstile by a mugger trying to grab her gold chain, which wouldn’t break. Instead she drove a Caprice Classic with velvet blue seats.

I couldn’t believe I was seeing her under the florescent lights of the subway car, amidst the advertisements for clear skin and hemorrhoid creams. She wore dangling earrings and looked glamorous. She seemed out of place, out of context in her stylish coat and high-heeled boots.

“Mom,” I said, loud enough for many to take notice.

“Lellybelle!” she said with a smile that embraced me.

I stood up, grabbed her arms, turned her in coordinated baby steps, and placed her in my seat. “What are you doing on the subway?” I asked

“My car broke down on 57th Street,” she said, brushing her brown hair out of her face.

She had been at a bridge tournament that day with her friend Mireille. She played all kinds of card games and was good at them. As we headed home together from the Forest Hills subway station along 108th Street, she told me that when she was walking down Lexington Avenue, she was overcome by perspiration, so much so that she went into a coffee shop and got napkins to wipe down her panty-hosed legs. “That’s weird,” I said. “Maybe you should go to a doctor.”

“Don’t be ridiculous” she said.

Instantly I stopped being ridiculous. We made a right on 68th Drive and were finally home.

Two days later, my mother collapsed.

That night as she was dying on the floral couch of our house, my sister, Debi, cradling her until the EMS arrived, I was on the subway. The trains were delayed. I got out at my exit; the air was arctic, my boots crunching on the snow, my breath visible in the night sky. Walking along 108th Street, I hopped aside as an ambulance went by, lights flashing and sirens wailing. I didn’t know it was racing down side streets to save my mother. I came home while they were trying to get her to breathe. A machine was doing it for her, and the ambulance took her to the hospital, but she was never able to wake up and breathe on her own. Four days later, declared brain dead, the apparatus was unplugged. For those four nights, my brother Dorian stood vigil at the foot of her bed.

Dorian and I left the hospital and made the arrangements at the funeral home and cemetery for a burial in the morning. That night, I fell into bed exhausted and depleted and finally went to sleep. I dreamed I was in bed with my mom having coffee. We were in her bedroom, which for some reason was on the first floor instead of the second, and we were wearing our nightgowns. Her gold bangles chimed as she lifted the cup from the saucer to drink. The doorbell rang. It was a couple, friends of my parents, a box of pastries in their hands. “Who was it?” my mom asked. “Valley and Marco,” I said and showed her all the goodies as if we had won a prize. As I was climbing back into the bed and getting settled for a grasse matinee, the doorbell rang again. “What’s going on?” my mom asked. I shrugged, ran to get the door to find more of her friends, and then got back into her bed. But as I snuggled next to her, smelling her smells, I realized that her friends, whom I’d known all my life, had looked at me with pity.

After the funeral, the friends who had populated my dream came to our door. It was the first night of the shiva. The friends had food just like in the dream, but my dream had been kinder.

I didn’t pick up Wuthering Heights again until the shiva was over and I had to go back to work. On the subway that morning, seated on the hard plastic orange seat, I opened the book to where I had left off.

The next chapter was the funeral of Catherine. I gasped. How had I stopped reading just before that point? Catherine saw Heathcliff again and was sick with regret. But I didn’t expect her to die. The shock of it made me cough out a sob. I closed the book and gathered myself. My mom was gone, brutally taken from me, like an excision. Here I was on the train, after an interruption of 10 days, going back to the mundane advertisements overhead like nothing had happened. But I had changed. I didn’t know how to be. I didn’t know how I was going to continue my life without my mother in it. I wasn’t ready to read a book and be in the subway. I wished I could look up and see her again, right there, stepping on my foot. My mom was in the hard cold ground in a cemetery in Queens, snow already covering her grave. The finality was savage.

My stop was next. I got up to leave the train, and with one last searching look, I stood clear of the closing doors.