Critically examine the symbolic significance of the leaves and the wind in Shelley’s Ode to the West Wind.

Or

/ “If I were a dead leaf thou mightiest bear;

If I were a swift cloud to fly with thee

A wave to pant beneath thy power”/

The leaves and the ‘winged seeds’ will play their part in the great cyclical rebirth of Spring, and the image of the seeds leads us also into the Christian resurrection of Easter. They lie ‘cold and low’ until awakened by the gentle wind of Spring, which suggests resurrection and Judgement Day as “she blows her clarion o’er the dreaming earth.” Examine the Ode to the West Wind in the perspective of symbolic imagery.

Or

Ellsworth Bernard identifies the spirit of the West Wind with the spirit of God, eternal love, Shelley’s hymn, in fact, the West Wind is I’m a sense the symbol of the Deity. The poet’s apparent triumph in the power of the West Wind in stanza 5 may seem like a departure from

Christian submission, but with his final, hopeful query he sinks into the passivity of the willed naturalistic cycle; / “O wind, If winter comes, can Spring be far behind? “/ Examine the passage in the context of the poem, Shelleyan Ode to the West Wind.

The poet himself is conflated within the hope of instrumentality or passivity and the trope of agency envisionings of / “Make me thy lyre even as the forest”/ and / “Be thou me, impetuous one!”/ And thus far this Romantic Metaphor as emphasized by MH Abrams in The

Correspondent Breeze “for the way the mind and the imagination respond to the wind”. In this poem the forest imagery is itself an Aeolian harp, the wind fingerings as it blows across.

But by deriving ‘from both’ the forest and himself ‘deep autumnal tone’ or elegiac consciousness of the mortality, the West Wind partake the poet’s own spirit of survival and sustenance. There is in Shelley’s Ode a movement through figures of sound into figures of light, towards a visionary and apocalyptic moment when sound and light become the same figure.

The poet’s function is no longer compensatory but revelatory or incantatory. The trumpet of a prophecy itself, is the same ‘clarion’ that will awakened the dreaming Earth. The West Wind, which once moved everywhere, has become a symbol for the poet’s own active and inspiring voice by some imaginative revision of the poet’s transmutability from passive instrument to active agent like the wind, itself.

Shelley’s profoundest reflections of nature and mankind associates the abstractest sublimity of wind blown and leaves strewn or driving wind and flying leaves decades observance of the western European landscapes of Italy. The first stanza of the poem describes the leaves flying before the wind blows, which is represented both as destroyer of the leaves and the preserved of the seeds from which new life will rise.

The poet’s fervent plea to lift as a leaf, a wave and a cloud to the invocation of the lyre and the power of the West Wind in order to achieve regeneration or resurrection which climaxes at the pinnacle of dead thoughts driven, scatters from an unextinguished hearth and being through lips that the celestial glory of the cosmic West Wind; there will arise in the cycle of the season a regenerating influence upon mankind.

The West Wind, as the destroyer of the old order and the preserved of the newer order, for Shelley, symbolized Change or Mutability, which destroys yet recreated all things; while the leaves signified for him all things, material and spiritual ruled by Change. The poem epitomizes Shelley’s conception of the eternal cycle of life and death and resurrection in the universe. The winds were to flutter at the gate of his imagination and the leaves were to rustle in the landscape of his mind.

Ode to the West Wind lyrics / “Drive my dead thoughts over the universe/ Like withered leaves to quicken a new birth!”/] and furthermore [ / “Be through my lips to unawakened earth/ The trumpet of a prophecy!”]. Percy Florence Shelley, the living symbol of Shelley’s own regeneration and so associated with the rebirth and regeneration symbolized by the Wind and the Leaves in the Ode to the West Wind.

To Leigh Hunt the poet authored on 12 November 1819 “Yesterday morning Mary brought little boy [Percy Florence Shelley] to me….You may imagine that this is a great relief and a great comfort to me amongst all my misfortunes, past, present, and to come. The birth of his child, a rebirth of himself in a sense, was perhaps the motif in the nexus of thought and emotion that inspired the composition of the Ode.

…

Nature poet Shelley’s visionary and mystic manifestations of ‘tameless’ and ‘swift’ and ‘proud’ and ‘uncontrolled’ and ‘fiery’ temperament are the personified embodiments in the allusiveness of strong, swift and masterful wind. The tumultuous tempest marks the end of Summer and the beginning of the autumnal monsoon season, and the assumption of being exalted and roused to be enthroned by the West Wind, that is literally the very breath of Autumn’s being.

The West Wind is followed by the Wind of Spring in the apotheosis of the azure sister of vernal blue haven. She is the feminine complement to the ‘impetuous brother’ by bring life to the ‘winged seeds’ which he had charioted to their dark wintry bed and so preserved. Leaves like ghosts [they are thin and frail] fleeing from enchanter; the winged seeds blown to the ground and buried like corpses in a grave, but in fact they repose in cradles to be reborn with the coming of the Spring.

Enlivening and invigorating imageries rather than burying and entombing imageries are symbolic manifestations within this paradoxical irony. / “O wild West Wind, thou breath of

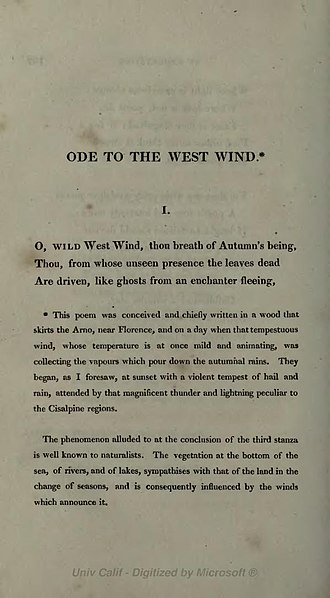

Autumn’s being/ Thou from whose unseen presence the leaves dead/ Are drive like ghosts from an enchanter feeling”/ / “The winged seeds where they lie cold and low/ Each like a corpse within its grave, until/ Thine azure sister of Spring shall blow”/

The West Wind is thus glorified above other winds, because which drives the dead leaves into corruption, is akin to the other West Wind ,which quickens the dreaming earth to life. Shelley’s invocation to the West Wind [“For whose paths the Atlantic’s level powers/ Cleaves themselves into chasms”] and furthermore, the poetic invocation of the lyrics recalls Shelley’s Essay on Christianity: “There is a Power by which we are surrounded, like the atmosphere in which some motionless lyre is suspended, which visits with its breath our silent chords, at will”.

Passive will-less attributes of nature dead leaves, seeds clouds, lulled Mediterranean has been transformed into he active and fearful cooperation of the Atlantic ocean with the terrifying power of the wind [‘share/The impulse of thy strength’]. The poet is ‘chained’ and ‘bowed’ by precisely those attributes of Wind embodied in ‘tameless’ and ‘swift’ and ‘proud’.

Shelley attained the emotional highpoint in the lines : / “Be thou, Spirit fierce! My Spirit! Be thou me, impetuous one!”/ —-the transition from supplication to command in the subsequent

imperatives [“Drive my dead thoughts”, “Scatter, as from an unextinguished flame” and “Be through my lips”] occurs during this utterance: “Be thou me, impetuous one! In the aftermath of the afterthought in supplication: / “Oh, lift me as a leaf, a wave, a cloud”/ and invocation to the lyre: / “Make me thy lyre even as the forest is”/. Shelley explicates the wind to be the spirit of agency through his plaintive and prayerful diction. Together these commands culminate in the ferment of the fervent plea that Shelley be filled with the spiritual being of the wind, that he become the wind.

George Santayana points out that Shelley is raised into sublimity by his participation in the West Wind’s immortal vital and this sublimity of the emphatic moment can be emphasized in the explanatory context of the critical interpretation: ‘…”Be thou me, impetuous one!”… The emotion comes not from the situation we observe, but from the powers we conceive: we fail to sympathize with the struggling sailors because we sympathize too much with the wind and waves. And this mystical cruelty can extend even to ourselves; we can so feel the fascination of the cosmic powers that engulfs us as to take a fierce joy in the thought of our own destruction. We can identify ourselves with the abstractest essence of reality, and, raised to that height, despite the human accidents of our own nature. Lord, we say, though thou slay, yet will I trust in thee.

The sense of suffering disappears in the sense of life and the imagination overwhelms the understanding.”

This breath of Autumn’s being is enthralling to Shelley because of the inscribed semantic cluster of wind, breath and spirit as ascribed to the desolate spirit of the European discontent; amidst post Napoleonic epoch to which society was deplorable chained and bowed especially the entire canvas of Italian landscapes blackened to the golgotha of winter. [ /The winged seeds, where they lie cold and low, /Each like a corpse within its grave, until/ Thine azure sister of the Spring shall blow:/] In the phase wintry bed is not a burial grave of dissolution but that of the haven for restorative sleep and anticipatory vision. Petition for transcendence and confession of the overthrow is amalgamated to be the fervent plea, ardent appeal, prayerful invocation, meditative reflection or rhetorical speech act of the adult life of a tragic struggler prophet poet revolutionary coalesced from the nostalgic boyhood introspective recollection: [ /Oh! lift me as a leaf, a wave, a cloud! I fall upon the thorns of life! I bleed!”/].

To Shelley’s poetic argumentative analysis, “There is no want of knowledge respecting what is wisest and best in morals, government and political economy…but we want the creative Faculty to imagine that which we know; we want the impulse to act that which we imagine; we want the poetry of life.” This passage is allusive in the parallelism in Ode to the West Wind: / “And by the incantation of this verse Scatter, as from an unextinguished hearth

Ashes and Sparks, my words among mankind!

Be through my lips to unawakened Earth

The trumpet of a prophecy!”/

Further Reading

Henry S. Pancoast’s Shelley’s Ode to the West Wind, Modern Language Notes, February 1920,

Volume 35, No. 1, pages : 97-100.

Patrick Swinden’s Shelley: ‘Ode to the West Wind’ Critical Survey, Summer 1973, Volume 3, No.

1 / 2, pages:52-58.

William H. Pixton’s Shelley’s Commands to the West Wind, South Atlantic Bulletin, November

1972, Volume 37, No. 4, pages: 70-73, South Atlantic Modern Language Association

I.J. Rapstein’s The Symbolism of the Wind and the Leaves in Shelley’s “Ode to the West Wind”

PMLA, December 1936, Volume 51, No. 4, pages: 1069-1079, Modern Language Association,

Brown University

Richard Harter Fogle’s The Imaginal Design of Shelley’s Ode to the West Wind, Source ELH,

September 1948, Volume 15, No. 3, pages: 219-226

Edward Duffy’s Where Shelley Wrote and What He Wrote For: The Example of the “Ode To The West Wind” Studies in Romanticism, Fall 1984, Volume 23, No. 3, pages: 351-377.

Coleman O. Parson’s Shelley’s Prayer to the West Wind Keats Shelley Journal, Winter 1962,

Volume 11, pages 31-37, City College, New York.

Jennifer Wagner’s A Figure of Resistance: The Visionary Reader in Shelley’s Sonnets and the “West Wind” Ode, Southwest Review, Winter 1992, Volume 77, No. 1, pages: 109-127,

Southern Methodist University