What function does mise-en-scene play in the composition of the atmospherics of a film? Substantiate with examples from the prescribed texts in the paper.

Mise-en-scene is the design and arrangement of actors in scenes for a theatrical or film production, both in the visual arts through storyboarding, visual themes, and cinematography and in narrative story telling through direction. It can be contextualized as the environment or milieu of the physical setting of an action [as of a narrative or a motion picture]. Light and camera, prompts and gadgets, costumes and apparel wear, pantomime and mime essentializes the abstraction of cinematic aesthetics—-mobilized and virtual gaze of the bodies and objects by sequential cluster or constellation of images [image fields] through kinesthetics of the montage in filmic frame is the canon of mise-en-scene—cinematic movements and cinematic effects within the cinematic tourism vistas; offering endowment of internationalization or hybridization of locales and cultures through cross bordering portability of diasporic films by digital reproducibility in montage or film editing [diffusion, dispersion, disruption, inversion, transportation, recontextualization] technique. The composition of the atmospherics of a film acknowledge negotiation between Albert Einstein and Walter Benjamin which can be explained in filmic language and cinematography. Einstein propounded the theory of the fourth dimension, extrapolating the intersections and overtones of visual and aural dynamics; Walter Benjamin characterizes this interweaving of body and images in digitally technologized reproducibility as the reception-of-a “state of distraction.” Mise-en-scene in a nutshell fosters the fundamental transferrable skills to the production and reception of a film and establishes the pragmatics semantic field of literary history and cultural memory.

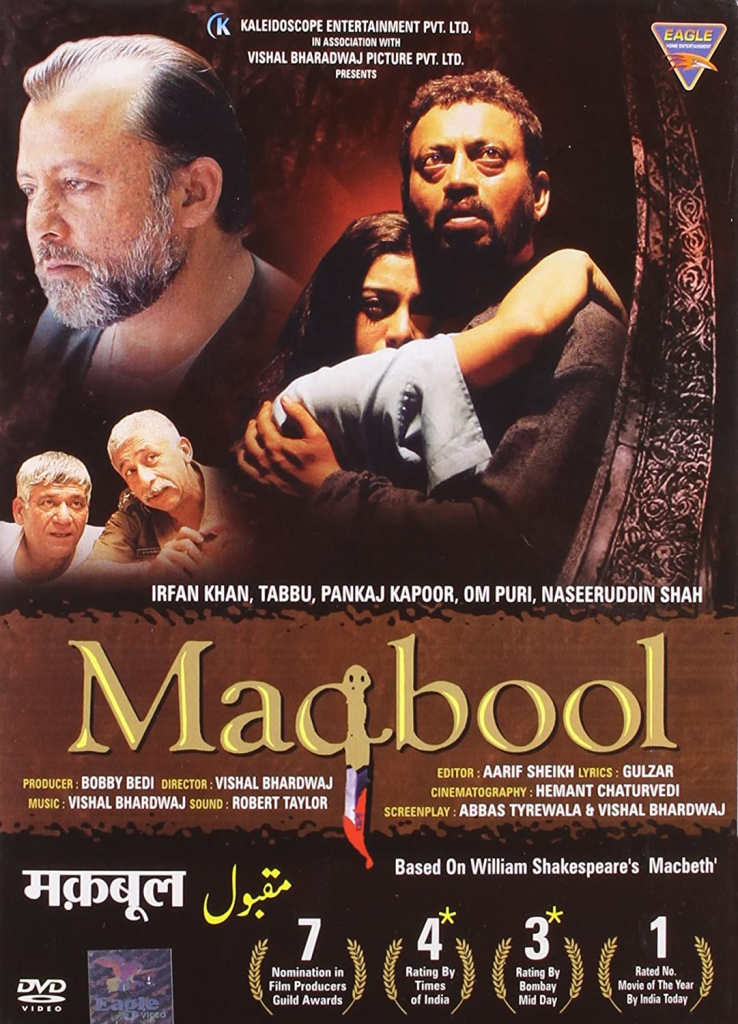

Reconsidering English playwright William Shakespeare’s Macbeth to the recontextualized adaptation of Indianized film production hybridizes Shakespearean Elizabethan England with the post independence and post colonialism mise-en-scene. “Maqbool” [2003] is critiqued by the directorial sententiousness in altruism of humane temperament which digresses the hegemony of cultural imperialism and/or cultural resistance as resonated in another blockbuster Bollywood cine picture talkies “Agneepath” [1990]. [Lord Hardinge, as governor-general, issued a resolution on October 10, 1844, declaring that for all government appointments preference would be given to the knowledge of English.—the instance of colonialism as symbol of the hegemony and /or resistance of imperial culturalism becomes the quintessential reference in film narratives.] Amitabh is the star cast heroic protagonist, gestures appeasement for the mother as lady of the hearth’s fiery temperament is immortalized with the imperative in the diegetic: “All the waters of Bombay will not cleanse the blood from your hands” resonates Shakespearean dialogism of somnambulistic Lady Macbeth. On the contradistinction, Vishal Bhardwaj’s Maqbool [2003] “Pure as the naked new born babe […] Shall blow horrid deed in every eye/ that tears shall drown the wind” in exemplification of treachery of the treasonous felony of Maqbool [slaughtering of Jehangir Khan Elias Abbuji] is the after effects/ aftermath of the seedlings of ambition matured by the profanation in the epiphany of Nimmi and the investigating law enforcement agency to a certain extent. This transgressivity is the depolarized effect in connotative diction that contextualizes futility of nihilistic anarchy in the “Throne of Blood” [1957]. Akira Kurosawa’s adaptation of Macbeth in the “Throne of Blood” [1957] illustrates the fruitlessness of worldly ambition and the limitations of free-will in Shakespearean rhetoric of the trajectory of Macbeth’s downfall—Macbeth’s tragic flaw is not the blind lust for power or vaulting ambition but the hamartia beneath the presupposition; that he was a free agent in a world where his actions are ultimately predestined or circumscribed; that tracks his degeneration from a poet-warrior into a merciless power hungry tyrant; hereby, shifting the mise-en-scene from medieval Scotland to postimperial post feudal Japan. Samurai Lord Tsuzuki resembles the cherubic-angelic saintly king—the prey of assassination by felon Washizu — the superimposed agent depraved of human agency and this masochistic emasculation blooms the impotency in a functionary character.

Since original Shakespearean film productions apparently disharmonize the audience of post colonial Indian subcontinent or Japanese post feudalism, hence the theatre drama has been altered through manipulation and interpolation of scenes, characters, actions, settings and plots—a frontality of presentation, declamatory and histrionic vocalization with rhetorical and visual flamboyance in hybridized performative of vernaculars—either pure and pristine or bowdlerized and indigenized. The mise-en-scene of long shots, deep focus, panning and tracking shots of Western realism and static frame and hard-edge wipe of Oriental formalism coalesces. Erin Suzuki’s “Lost in Translation: Reconsidering Shakespeare’s Macbeth and Kurosawa’s Throne of Blood” notes, “Kurosawa’s Shakespeare is inevitably—-and fortunately more Kurosawa than Shakespeare. With blunt and vital irreverence, the director has translated Shakespeare’s words into Japanified images, Shakespeare’s lords into Japanified barons […] the spectator scarcely has the time to realize, that the images deafen and the noises colour his imagination, that he is experiencing the effects of cinema seldom matched in their masculine power of imagination.” Nonetheless this hybridization and fusion of mise-en-scene in “Maqbool” [2003] is justified in the language of Vishal Bhardwaj “My film is not meant for Shakespeare scholars […] My interpretation is not text-bookish […] I have tried to remain true to the plays spirit than to the original text.”

How do literature and cinema intersect each other? Explain through the examples of literary and cinematic texts in this paper.

“Margarita With A Straw” interweaves themes and motifs of Charlotte Bronte’s “Jane Eyre” through mise-en-scene of canonical hermeneutics of the aesthetics and cultural anthropological readings by paradox: gendered expectations and gendered realities. Gender and disability studies of “Margarita With A Straw” can be recontextualized in the montage of filmic feminine narrative of the Victorian bildungsroman in the critical lens of Sandra Gilbert and Susan Gubar, “seems to be the projection of their own despairs into the passionate and even melodramatic characters, who act out the subversive impulses that every woman feels when she contemplates the deep-rooted evils of patriarchy.” Kalki Koechlin [Laila] the cerebral palsy undergraduate faces rejection and disavowal by the lead singer of the musical society whom both of them workshops. She, nonetheless, casts spectacle and marvel in the wonderment to fulfill a prospective semester to dreamland destination: New York University. Jane Eyre’s narcissistic rage, forlorn depression, habitual mood swings, epistemological anxieties, solitary solipsism as embedded in virulent passion, maverick temperament and rebellious mutiny are implicated to be strains of femininity with the protagonist of “Margarita With A Straw”. As literary history and cultural memory traces us to ponder the literariness of the Brontean novelistic textual adaptation becomes the quest of figurative language of filmic interpretation: “A Christmas frost had come at midsummer; a white December storm had whirled over June; ice glazed over ripe apples; drifts crushed the blowing roses; on hayfields and cornfields lay a frozen shroud”—-this dialogism is recontextualized in the spirit of Jane Eyre’s personae as linnet, imp, fairy, sylph, brownie, pixie, sprite, salamander and even a thing; whose clandestine bigamous love affair in Thornfield with Edward Fairfax Rochester blooming by the foreshadowing of fruitlessness and futility is objectified in the subjective gaze of the filmic diagesis as Kalki Koechlin [Laila] consummated into romance and sexual relationship with Jared in New York—resonances of the heroine as corrupted and dismantled sylph like fairy of gendered expectations. In terrains of gender and disability studies, subaltern and marginalized voices akin to the narratorial perspective and point of view in Laila [Kalki Koechlin] culminates the dichotomies by the polarities between taboos and conventionalities or stereotypes and bigotries in context of relationship and wedding, love and romance, puberty and pregnancy. Gendered realities have thwarted the expectations of a betrothal for the feminine disability as harmonized by the unification of the myths: undesirability and asexuality. Recollections and impressionistic readings gleaning from archives and documentaries of the film production incarnate to resurrect marginalized disability voices of the feminine gendered expectations dispelling the myth of undesirability or asexuality.

From creative writing classes with Jared to activism with foible like personage in Khanum, Laila [Kalki Koechlin] reinterprets relationship as if her life visualizes envisioning of the Jane Eyre’s exposure of liberty and egalitarianism when the Brontean heroine reclaims: “I am no bird; and no net ensnares me; I am a free human being, with an independent will: which I now exert to leave you.” Cinematic gaze of the subjective focus in the close up of Laila and Khanum as depersonalized care-givers of altruistic triumphalism reechoes the allusion to Jane Eyre and St. John River’s associationism. St. John Rivers—the missionary apostle, epitome of pilgrimage to sainthood and divine destination implores in exhortingly assertive tone: “A missionary’s wife, you must — and shall be. You shall be mine; I claim you— not for my pleasure, but for my Sovereign’s service” Or even alternative reading would suggest Helen Burns’ and Miss Maria Temple’s as influencers of Jane Eyre’s philosophical transcendentalism sermonizing preachings of morality and integrity, which sanctifies the memorial of their ultimate detachment. “to gain some affection from you[Helen Burns], or Miss Temple, or any other whom I truly love, I would willingly submit to have the bone of my arm broken, or to let a bull toss at me, or to stand behind a kicking horse, and let it dash its hoof at my chest.” “ “If all the world hated you[Jane Eyre] and believed you wicked, while your own conscience approved you and absolved you from guilt ,you would not be without friends”—this aphorism of Helen Burns later leads to fruition in the blooming springfield of Laila with the deep focus and subjective close up of fantasizing despite past of tempestuous upheaval in the brink of discontinuities, complexities, intricacies, ironies and subtleties such as the bereavement of advanced stage colon cancer affected mother and entanglement of detachment by dissociating her camaraderie with the former romancers and coquettes. Walter Benjamin’s inevitability of the on-screen camera to the receptivity of filmic audience extrapolates, “While facing the audience, he knows that ultimately he will face the public, the consumers, who constitute the market.” This filmic language can be relocated in the epilogue of the denouement: “Margarita With A Straw”. Interestingly this expressionistic freedom of choice creates vivid and impressionistic reading of Jane Eyre: “Do you think, because I am poor, obscure, plain and little, I am soulless and heartless? You think wrong!-I have as much soul as you ,-and full as much heart! And if God had gifted me with some beauty and much wealth, I should have made it as hard for you to leave me, as it is now for me to leave you.” Intertextuality of the close critical reading emphasizes that Laila would have a life of alienation in existentialist formalism unless God favours in privileging the bestowal to alleviate her deformity along with redemptive potential of individual agency.

Film critic Walter Benjamin notes of the screen actor’s relationship to the camera never enables him to forget the audience: “While facing the camera, he knows that ultimately he will face the public, the consumers who constitute the market”. Examine the Charlie Chaplin’s Modern Times [1936] in the age of mechanical reproduction.

Charlie Chaplin’s trump as silent pantomime of the film production is the flopping mise-en-scene in contrast to the talking pictures burgeoning popularity that diminishes the former’s familiarity. David James suggests that “a film’s sounds and images never fail to tell the story of how and why they were produced—–the story of their mode of production”; in Modern Times the same holds true of the story whose images tell about how they were received, the story of their mode of consumption. Opulence of the mass production of Americana materialistic consumerism stages the grandiosity of mise-en-scene in the departmental store sequences, that projects feminine proprietorship as satirized in the eagerness to satisfy the gamin’s needs and wants harboured by the contrasting daydream of the home ownership by the Trump phantasmagorial spectre.

Film critic Walter Benjamin distinguishes between the theatrical and cinematic performances as: “The artistic performance of the stage actor is definitely presented to the public by the actor in stage, that of screen actor, however, is presented by a camera…Guided by the cameraman, the camera continually changes its positions in relation with the performance. Thus in filmic language, close up of the glaring talking industrialist capitalist [president of the Steel Factory Trading Inc.] imperative “Quit stalling, get back to work!” to the misdemeanour of the employee—- langorous solitude of cigar’s privacy is a poignant dramatization. The factory worker not only oversee as omniscient purveyor scrutinizing through digital surveillance but also appears as a magnified ubiquitous mighty power through his focal subjectivity on the screen. Even emphemeralism of the short-lived respite acquired through lunch break is flummoxing when Trump is exploited as a guinea pig on whom the President of the Steeling Inc. thrust to the impetus of experimental Billow’s Feeding Machine. Swashbuckling Charlie Chaplin’s friend Douglass Fairbanks wrecks havoc spotlighting the carnivalesque of the ‘misfit’ which society prescribes as a stint in the sanitarium.

“Science finds, industry applies, man conforms” Chicago’s century of progressive technocracy movement in the epochal boosterism reflect counterveilling pessimistic outlook towards such radical and revolutionary advancement —–automaton replacement of labour market. Trump personae is polarized between the Taylorites’ advocacy for enhancement and enrichment of the labour forces’ practical efficiencies favoured by cinematic exposition and the Edisonian disdain for entertainment of filmic broadcast—–Trump personifies humour, pathos, romance for compelling audience’s gaze. Nihilistic monotony and gruesome grumpiness pervades factory experiences of the assembly lines and firm working stations from pastoral countryside by the cinematic montage form shifting perspectives of spatiotemporality as imbued by cultural memory and literary history —–allegorizing “a story of industry, of individual enterprise——humanity crusading in the pursuit of happiness.” There and then, Charlie Chaplin’s projection of the destabilization of machine-making culture of contemporaneous society achieved spectacle in the marvellous film entertainment industry as depicted by the outcast Trump personae ostracized by the follies of frailties, institutional authorities and dumb luck.

Further Reading

Lawrence Howe’s Charlie Chaplin In The Age of Mechanical Reproduction: Reflexive Ambiguity In “Modern Times”, College Literature, Winter 2013, Volume 40, No. 1, pp. 45—–65.

Examine the relationship between literature and cinema in the context of intertextuality with references to Macbeth and Throne of Blood.

“Kurosawa’s Shakespeare is inevitably—-and fortunately——involves more Kurosawa than Shakespeare. With blunt and vital irreverence the director has translated Shakespeare’s words into Japanese images, Shakespeare’s lords into Japanese barons […] the spectator scarcely has time to realize, as the images deafen and the noises decorate his imagination, that he is experiencing the effects of cinema seldom matched for their headlong masculine power of imagination.” Film critic Jerry Blumenthal suggests that Throne of Blood was no pale imitation of Shakespearean tragic film Macbeth but “a serious, dynamic and autonomous work of art.” The scenarist’s vision is constant with Kurosawa transforming poetic language into visual imagery. New York Times film critic Bosley Crowther found the adaptation to be “grotesquely brutish and barbaric” since Kurosawa’s cross cultural and cross medium adaptations of Macbeth is neither merely a grotesque Japanified version of Shakespeare’s tragedy not a tragic transposition of the play’s essence into the universal visual images, rather, it stages a historically specific negotiations between traditionalist Japanese and imported Western culture. Kurosawa’s adaptation of Macbeth in the Throne of Blood illustrates the fruitlessness of worldly ambition and the limitations of free-will in Shakespearean rhetoric of the trajectory of Macbeth’s downfall—–Macbeth’s tragic flaw is not the blind lust for power or vaulting ambition but the hamartia beneath the presupposition and preconception that he was a free agent in a world where his actions are ultimately circumscribed, that tracks his degeneration from a thoughtful poet warrior to a merciless power hungry tyrant. Samurai Lord Tuzhuki resembles the guiless King Duncan “whose virtues plead like angel trumpet tongued” is assassinated by the treachery of the felon Washizu through theatricality of a naturalized chain of events since Washizu is even depraved of free human agency and this emasculated masochism blooms the impotency as a merely functionary character. Frozen Washizu’s grimacing face of the warrior mask, Heida’s possession by the spirit of the cinematic apparatus and the zeno’s paradox. The use of long shot, deep focus, panning and tracking shots emphasize the realistic style championed by Kurosawa’s Western contemporaries such as film critic Andrew Bazin and director Houston, while the use of static frame and hard edge wipe comes from Japanese cinematic practice. Peter Donaldson suggests that the juxtaposition of Western realist and Japanese formalist traditions in the Throne of Blood represent Kurosawa’s temptation by, but ultimate disavowal of “Westerns modes of representation and Western values.”

Agneepath mafia don Amitabh’ sanitizing and disinfecting of hands as oblationary obeisance in mother’s presence as a gesture of appeasement is ironically bemused by the filmic dialogue quoted from Shakespearean theatricality that “all the waters of Bombay will not cleanse your hands […]!”—-obvious and succinct lines of Shakespeare from the sleep walking scene of Lady Macbeth. The commercial Hindi pot boiler chooses to borrow lines from as canonical a figure as Shakespeare—-a unique appropriation, intertextuality and absorption of the conjugality between Shakespeare and the Bollywood mainstream Indian cinematic film production and reception. Nonetheless Shakespeare’s Jacobean England did not harmonize with the post colonial Indian subcontinent since the plays were being altered through interpolation and manipulation of scenes, characters, actions, settings, plots—-a frontality of representations, a declamatory and histrionic vocalization with a rhetorical and visual flamboyance in the hybrid performative mode of vernaculars—either pure and pristine or bowdlerized and indigenized. In 1844 Lord Hardinge, the Governor General of British colonial India, passed a resolution assuring preference in government employment for those who acquainted with European Literature; might be implicated as an act of cultural resistance , upstaging the hegemony of the imperialist Englishness. Maqbool [2004] postcolonial and post independence reimaginings of literary heritage turning war torn Scotland into Mumbai gangland presided over by the aging Jehangir Khan Elias Abuji and his right hand man Maqbool. Vishal Bharadwaj critiques: “My film is not meant for Shakespeare scholars […] My interpretation is not text bookish […] I have tried to be true to the play’s spirit than to the original text.” Treacherous transgressivity of Maqbool is the after effect of the seeds of ambition challenging manhood through the feminized sexuality of Nimmi. The transposition and illustration of the utmost graphic and aural scene is visualized in the dramatization of “Pity like a naked new born babe […] shall blow horrid deed in every eye/that tears shall drown the wind”

Further Reading

Erin Suzuki’s [University of California, Los Angeles] “Lost in Translation: Reconsidering Shakespeare’s “Macbeth” and Kurosawa’s “Throne of Blood”, Literature/ Film Quarterly, 2006, Volume 34, No. 2, pp. 93-103, Salisbury University

Poonam Trivedi’s [University of Delhi] “Filmi” Shakespeare, Literature/ Film Quarterly, Volume 35, No. 2, pp. 148-158, Salisbury University.

Examine the Americana production of Ridley Scott’s Thelma and Louise in filmic language.

Thelma Dickinson [Geena Davis] and Louise Sawyer [Susan Sarandon] is best reviewed as a feminist manifesto [the heroines are ordinary women driven to extraordinary ends by coercion of patriarchy] and as profoundly antifeminist [the heroines are dangerously phallic caricatures of the macho violence they are supposedly protesting]. This entertaining and picaresque tragicomedy is a vivid portrait of contemporary Americana where women are still struggling to redefine their individualities; it is a symbol of feminine inconsistencies. Louise Sawyer [Susan Sarandon] and Thelma Dickinson [Geena Davis] are symbols of mimetic female escapism —-urgent undercurrent of American society that seems to cultivate a mostly unfulfilled yearning for women to run away the boredom and sexual entrapment which they are condemned; ie Jimmy [Michael Madsen]’s infatuation disillusions the romance in the former and Daryl [Christopher McDonald]’s eroticism exasperates the amorousness of the later. J.D. [Brad Pitt] exclaims Thelma’s husband as an asshole which she confesses in the affirmative of “he is an asshole. Most of the time I let it slide.” Connotes the burlesque of the pun and staccato humour in the screwball tradition. Burglary of Thelma stunningly shocks Louise , who later reunites through mingling in the spell of exhilaration as the screwball couple goofs to ride the motorcycle together as outlawed persona. Thelma and Louise have no flashbacks and flashforwards, and hence bereft of voice-over. The butchering Harlan and the escapement of the girls from the investigating police is the fissure launching parallel montage in the sustained and fleeing to facing off at Grand Canyon. Thelma after murdering lies inert on a motel room, then sits in a glaze by the pool; Louise after the theft of the money sits on the floor of another motel room in a stupor.

Further Reading

Harvey R. Greenberg, Carol J. Clover, Albert Johnson, Peter N Chumpo II, Brian Henderson, Linda Williams, Marsha Kinder and Leo Braudy’s “The Many Faces of Thelma and Louise”, Film Quarterly, Winter 1991-1992, Volume 45, No. 2, pp. 20-31, University of California Press.