Examine Mary Oliver’s Sleeping in the Forest, Twelve Moons with critical commentary.

“The special puzzle of Romanticism is the dialectical role that nature had to take in the revival of the mode of romance. Most simply, Romantic nature poetry, despite its long critical history of misrepresentations, was anti nature poetry […] Romantic or internalized romance […] tends to see the context of nature as a trap for the mature imagination.” Harold Bloom’s The Internalization of the Quest Romance

“It is the destiny if consciousness […[ to separate from nature, so that it can not only transcend not only nature but also its own lesser forms.” Georey Hartman’s Romanticism and Anti Self- Consciousness

Bloomian and Hartmanian tradition of Mary Oliver’s romantic nature poetry dichotomizes the antitheses between nature and self, body and soul, consciousness and unconsciousness, subject and object, nature and culture, language and muteness, death and immortality, imaginative speaker and immature child, transcendence and immanence. The speaker of the poem recollects the mystical closeness and amity with the natural world as suggested by the ritualizes camp trip sojournings in the forest floor of the maternal earth engulfs her like “as if she feels in water”. Herein the poet laureate superimposes the visionary selfhood upon “a stone on the riverbed”; because her drowsiness is not a blankness but the labyrinthine “lichens and seeds”.

The poet and the speaker impersonate Wordsworthian philosophical mind and Yeatsian Artice of Eternity through mimetic imitation of rocks, stones and trees of Wordsworth “A Slumber Did My Spirit Seal”. Witches, spinsters, crones and mother nature begin to speak for themselves, they transvalue their romantic forefathers’ mythic assessments as they defy the doom of muteness placed on all these female others who inhabit masculine poetic landscapes. Mary Oliver’s poetic revolutions embody mystical consciousness and experience of renewal. From the core of the heart’s engravings, Oliver’s everlasting bonding with nature in the face of sober truth memorializes the unity of the natural despite forsaking the association of supernatural eternity; her poems follow the cycles of the seasons to image loss and the possibility of renewal. Linda Gregerson reviews noteworthily, “She is not so much moved by the works of man, and she somehow contrives to love the world more than she loves language, no common feat for an artisan who works in words.”

Gratitude and reverence of the lyrical naturalist’s ardour of romantic nature poetry proclaims testimonial “I am sensual in order to be spiritual” amidst postmodern milieus. There is a fusion of Transcendental, Buddhist and Christian imageries grounded firmly in the earth, which Oliver views as God’s corporeality. Contemporary mystic of American poetry Mary Oliver stalks the edges of the marshes, journeying deep into the forests to open her breast to the known and the unknowable “as if the edge of sweet sanity” where “wild blind wings open” to interrogate nature of the soul, about its relation to the earth, about the damage of dualism it seeks to separate soul from body, body from earth and earth from the ultimate mystery of the immeasurable and unutterable nature of God heralded by Enlightenment.

Mary Oliver’s rapture with the nature such as the creatures of the wood and the sea, birds of the air, plants of the elds, trees of the forests—this is the liturgy of living things that the poet consistently dwells with and upon the elusiveness of the never-ending rosary.

Further Reading

Janet McNew’s [St. John University] Mary Oliver and the Tradition of Romantic Nature Poetry, Contemporary Literature 1969, Volume. 30, No. 1, pp. 57-77, University of Wisconsin Press Journals Division

Todd Davis’s The Earth as God’s Body: Incarnation as Communion in the poetry of Mary Oliver Christianity and Literature, Summer 2009, Volume 58, No. 4. Pp. 605-624

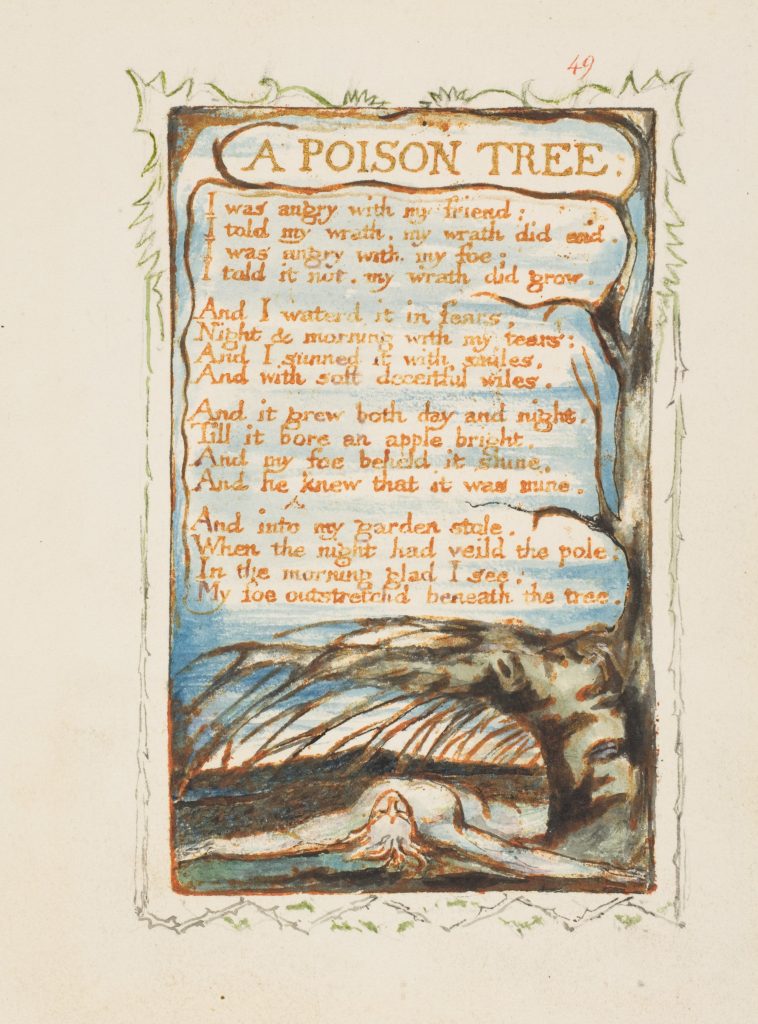

Examine William Blake’s A Poison Tree with critical commentary.

“A Poison Tree” is a counter myth which expresses the Biblical narrative of the Fall as a tree burlesquing the “Tree of the Forbidden Fruit”. Forbearance of the Wrath of God is anticipated in the allegorical symbolism of the poisoned tree as poetic vehicle, abstraction of human situation [repressed anger]. “I was angry …;/…my wrath did end.” propositional content and grammatical structure clash with substantiation of adjectival noun from angry towards wrath or indignation manifested as seven deadly cardinal vices that these lyrics implied in the metamorphosis of the whole poem. “I was angry with my foe, /I told it not, my wrath did grow.”——this couplet’s propositional content concerns the intensification of emotion, a subject now reinforced by the shift from angry to wrath. The shift is mediated by the pronoun “it”, which is indeed in this lyric Janus-faced part of speech; wrath can be cultivated following the verbs “watered” and “sunned”: “And I watered it in fears/

Night and morning with my tears;/ And I sunned it with smiles;/And with soft deceitful

wiles.”——–

Wrath is watered and sunned with fears, tears and soft deceitful wiles; water’s alkalinity provides nourishing nutriment for the sustenance of the poison tree as the language oscillates between the conceptual and the phenomenal to provide a tangible equilibrium between the tenor and the vehicle. “And it grew both day and night/Till it bore an apple bright” —–herein the intense cultivation of anger culminates in literal incarnation which the poem’s conclusion is the incredible transformation despite the occurrence that cannot be gainsaid: “And my foe beheld it shine/And he knew that it was mine/ And into my garden stole/ When the night had veiled the pole/ In the morning glad I see, /My foe outstretched beneath the tree.”

Blake intends us to take the embodiment of deep malice and disdain to be the literalization of Milton’s Satanic forbearance from the forehead by the conceiving of sin. Objects become extensions or projections of the human agency as exploratorily examined in “A Poison Tree” in which the correspondence between human and the natural is […] pronounced […] “the apple bright of the poem” suggest [ing] […] a process where intense emotion repressed, because of binding social codes, is rendered into a tangible symbol.” The power of mind transcends that of the power of the matter in Blakean perspectives and poetic appreciation anthropomorphizing the inanimate and insensible to be personified symbolism of realistic living forms rather than mere poetic device of similitude.

Since […] “These poets knew that “All deities reside in the human breasts and their poetic tales or mythologies were imaginative account of imaginative reality and thus true” In other words, that the virtue of Christian forbearance is the psychological repression mythopoetically. For Blake the truth behind Genesis is that emanates anciently—and paradigmatically ——-a sneaking serpent of a man sought in the vested venture of vengeance blossoms into a fascinating macabre of incarnational narrative within

hermeneutic tradition.

Further Reading

Phillip J. Gallagher’s [The University of Texas at El Paso] The Word Made Flesh: Blake’s “A Poison Tree” and the Book of Genesis, Studies in Romanticism, Spring 1977. Volume 28, No. 2, William Blake 1757——-1827, Spring 1977, pp. 237—–249.

Z. I. Mahmud,

Both instances of critique are very well composed.

I’ve particularly enjoyed your critique of Oliver. Personally, I’m a great aficionado of this particular facet of the human condition i.e. dichotomy, and ruminate on the said phenomenon/notion excessively in my own poetic discourse, too.

My felicitations to you on producing an engaging critique of as historically and poetically significant poets as Oliver and Blake.

Thank you for sharing your work with us.

Best regards,

Saad Ali

Pingback: englishliterature