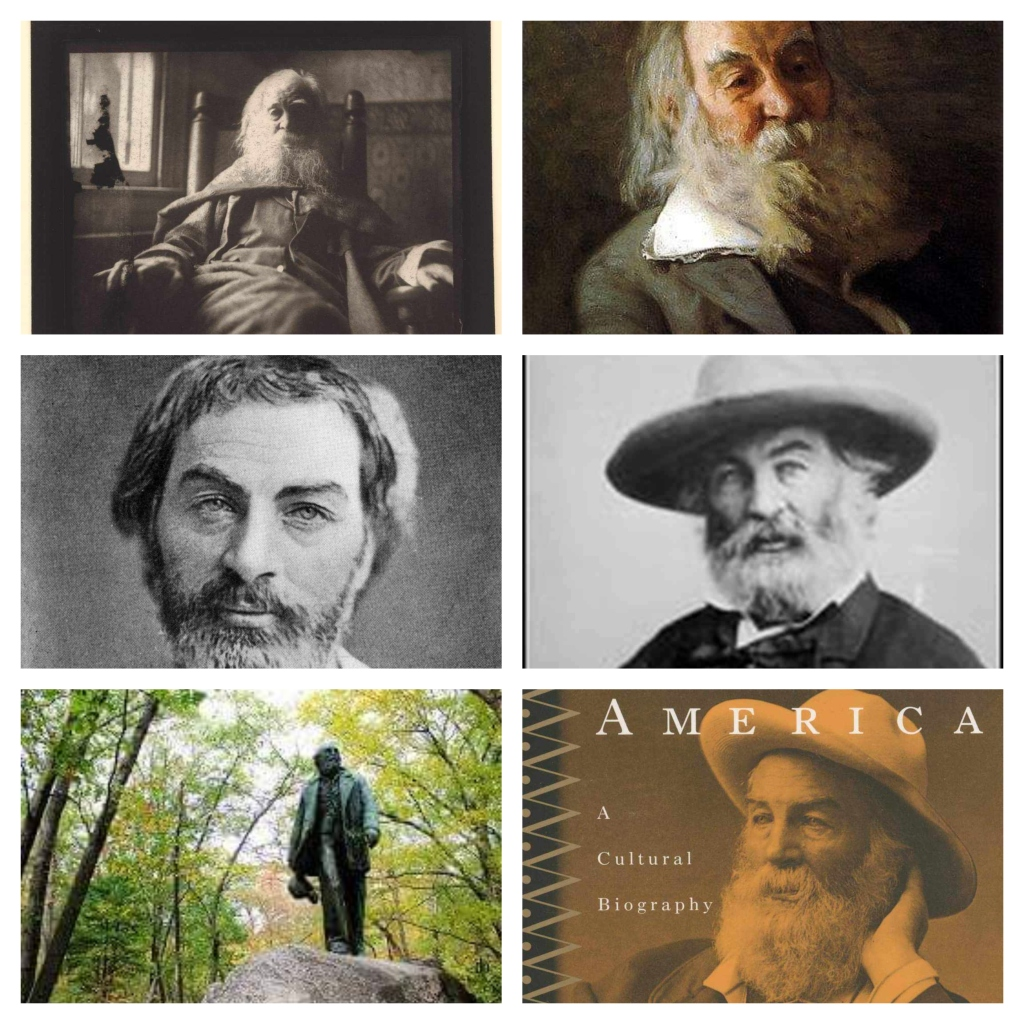

Written in memory of President Abraham Lincoln, to whom the poem refers as the captain of the ship of state by the master of Lincolnian verses. “O Captain! My Captain!” have parallel readings in analogy to “When Lilacs Last in the Dooryard Bloom’d” as transcendental poems by Poet of the Civil War, Walt Whitman. Grieving the lamentable bereavement of President Abraham Lincoln in contextualizing the universal implications of spatiotemporality as if there was the endowment of everyman’s elegiac dirge-like hymnal observance in the commemorative spirit of the cultural imagination.

Lincoln’s death is absorbed and re-coded as an extended metaphor, a projection of the speaker’s imaginative fantasy relating the objective historicity of memorial. “My Captain” is not only a term of endearment and loyalty, but a claim upon the person in correspondence to the solidarity and camaraderie of brethrenship in contrast with the acknowledgement and celebration of death as the end of all suffering that is especially true when considering “When Lilacs Last in the Dooryard Bloom’d”: the poem transports readers from a trinity of stimuli; that reminds the speaker’s of Lincoln’s heartless and inhumane cessation of life as observable in Lilacs newly bloom’d; “the great star early dropped in the Western sky in the night” and the “ever-returning spring” to the memory of Lincoln’s funeral procession “the coffin that slowly passes” on which the speaker leaves a “sprig of lilacs” … “but, praised! Praised! Praised!“ / “For the sure unwinding arms of cold enfolding death”. Social phenomena are encountered and absorbed as a kind of inseparable hyperconsciousness as apparently evidenced in the anthology Leaves of Grass .

The Lincoln poems are instances of the presidential death by assassination that resonates within the speaker’s mind whether in the crisp and condensed epitaph “This Dust Was Once The Man” or the deep languid reverberations of “But O heart! heart! Heart!” / “O the bleeding drops of red,”/ “Where on the deck my captain lies,” / “Fallen cold and dead.” […] “It is some dream that on the deck”/ “You’ve fallen cold and dead” […] “But I with mournful tread,”/ “Walk the deck my Captain lies,”/ “Fallen cold and dead.” Whitman’s elegies re-enacts and aestheticizes the mourning process; they revel in the lush subjectivity of the speaker as emphases of the stanza revelations manifest through floral laurel wreaths: “For you bouquets and ribbon’d wreaths—- For you the shores’ a -crowding” / “For you, they call the swaying mass, their eager faces turning.”

Walt Whitman finds the stature of Abraham Lincoln to be visionary, practical, prophetic, messianic and shrewdly realistic; Lincoln in Whitmanian perspectives was the poetic Shakespearean exhibited in both private and public affairs; Americanness symbolic of the roughs and beards, space and ruggedness and nonchalance literally anti dandified but prairie stamped character. “O Captain! My Captain!” is a rhetorical statement of the paradox involved in the president’s dying in the consecration and veneration of the brave heartedness and heroism. The Captain is also the speaker’s father as noted here: “Here Captain! dear father!/ This arm beneath your head! It is some dream that on the deck/ You’ve fallen cold and dead.” The figure of Lincoln shone over brighter despite the tragic incompleteness of his achievements: “Exult O shores, and ring O bells!/ But I with mournful treads, / Walk the deck my Captain lies,/ Fallen cold and dead.”

Walt Whitman’s transformation was grandiose and loftier in shifting and changing from the poet of the body to the poet of the soul, thus becoming poet of internationalism and cosmic from intense nationalism. This is crystal clear in the eloquence of the gratified poetic personality of Whitmanian spirit: […] “no more smart sayings, scornful criticisms or harsh comments upon persons or events, or private and public affairs […] never attempt puns or play upon words or utter sarcastic comments.” Passage to India foreshadows Walt Whitman’s fusion of traditional and philosophical speculations, contemplative reflections and poignant meditative perspectives of spiritual being in temporality towards immortality. “Divine efforts of the heroes and their ideas faithfully lived upon” symbolize Columbus as major figure within the allegorical symbolic background reading contextualizing the completion of the Union Pacific Railroad in May 1869 and the idea of the mystic passage of the soul to India. In addition to these scientific accomplishments including the Suez Canal connecting Europe to Asia and the Transatlantic Cable. Material and spiritual fulfillment prophetically revealed through “Passage to India” cloaked by the awkward enterprises of captains, engineers, explorers, voyagers, and scientists; and the mystification of the poet laureate merging with the Christian spirit: “Nature and man shall b disjoin’d and diffus’d no more/ The true son of God shall absolutely fuse them.”

Walt Whitman’s verbal melody and pictorial picturesqueness quintessentially enshrines the poetic aesthetics enfolded by the traditional and orthodox organic form and structure of art-nature analogy in “Passage to India!” . The passage literally refers to tangible reality of the transcendental American revolutionary achievements of scientific progress including the transcontinental railroad, the transatlantic cable and the Suez Canal while the surface metaphoricity of the cloaked textuality engraves the embodiment of enlightenment illuminative of labyrinthine alleyways from the discovery of knowledge to the advent of faith and spirituality as proclaimed by the declamatory phrases from the perspectives of the authorial viewpoint that dispels mysteries and enigmas of explorers, adventurers, voyagers and expeditionists.

Walt Whitman’s “Passage to India!” is a metamorphoses that occurs by the transposition, superimposition, transportation and transformation and/or flowing from descension to ascension through the cyclical flow of thoughts and feelings in the allegory of the biblical genesis of human individuals mounting to their deity in supplication of salvation and atonement. Organic evolution follows this metamorphoses towards meaning and effect between the continuum of changing and shifting. Form the point of view of multifaceted visages of poet, biologist and astronomer, God divines the cosmic power of celestial order with effulgence of phosphorescence to light, water, fountain and emotional tranquility. Crowning voyage of the individual returning to the soul paves the restoration of the younger kinsman melting in the fondness of the elderly sibling for the sake of death as comradeship fulfilling in itself. Pulse-like radiations of energy animate the poetic world of spiritual reality. Changing, shifting and evolving nature of life comes into perspective through the cycles of renewal within the pulse-like radiation. “Bathe me O God in thee […] seas of God” resonates the streams of Gangetic and Indus basins and their affluents; thoughts move like waters flowing in analogy with the rivulets running throughout literary history and cultural memory. In other words, projections of specificity in the historical trajectories implicate the spirits of the succumbing explorers descending and sinking down the slopes.

“Down from the gardens of Asia, descending radiating/

Adam and Eve appear, then their myriad progeny after them,/

Wandering, yearning and curious with restless explorations,/

With questionings, baffled, formless, feverish with never happy hearts,/

With that sad, incessant refrain, Wherefore O unsatisfied soul?, and whither I mocking life?”

Fortunate fall shrewdly points to the Biblical genesis referencing the allusive nature of allegorical transcendentalist humanity heralded by the spirit and matter. In this sense, frustration, despair, disillusionment, void, melancholia are implicated as inevitable premise of hybris in individualism. “Columbus walking in footlights in some great scena” notes Whitman of “[t]he sunset splendour of chivalry declining” to “misfortunes, culminatos[…] dejection, poverty and death.” Rediscovery of the Orientalists through “ascending body and spirit mounting to heaven” reinforces “the towers of fables immortally fashioned from mortal dreams.” Richard Chase in Walt Whitman Reconsidered has examined the relinquishment of poetry and the upholding of speech-making or oratorical quality as exemplified by the critical passage:

“The musing, humorous, paradoxically indolent but unprecedentedly energetic satyrs poets of the 1850s becomes the large, bland, gray personage with the vague light blue eyes and circumambient beard. Dionysius becomes not Apollonian but positively Hellenistic—prematurely old age, […] soothsaying, spiritually universalized. The deft and flexible wit disappears along with the contrarieties and disparities which once produced it. The pathos, once so moving when the poet contemplated the disintegration of the soul or felt the loss which all living things know, is now generalized out into a vague perception of the universal.”

Further Reading

Scott Borchert’s Lincolniana, “Southwest Review” Volume 100, No. 1, pp. 12-21, Southern Methodist University

Stanley K. Coffman Jr’s [University of Oklahoma, Norman] Form and Meaning in Whitman’s “Passage to India”, PMLA, June 1955, Volume. 70, No. 3, pp. 337-349, Modern Language Association Press.

Arthur Golden’s [ City College City University of New York] Passage to Lesser than India: Structure and Meaning in Whitman’s “Passage to India”, PMLA, October 1973, Volume. 88, No. 5, pp. 1095-1103, Modern Language Association

David Daiches’s Lincoln and Whitman, Johrbuch for Amerikastudien, 1996, pp. 15-28