Puritan England New Orleans postmodern authoress Kate Chopin’s The Awakening explores the feminine subjectivity through dichotomies and/or antitheses between the self and society unfolding maternal discourse and self-possession in corresponding light of sensuality, sexuality, autonomy and adultery. Edna Pontellier’s denial to be “reintegrated into the existing order of the bourgeoise patriarchal society […] challenges less a particular institution than the entire organization of society […] the outward existence which conforms and the inward life which questions […]Mrs. Edna Pontellier was beginning to realize her position in the universe as a human being and to recognize her relations as an individual to the world within and about her.”

In her despondent vigils the night before her bereavement, this vivid image comes to her mind, “The children appeared before her like antagonists who had overcome her; who had overpowered her and sought to drag her into the soul’s slavery for the rest of her days. But she knew a way to elude them.” Children loomed in gigantic proportions in her final meditations as slave drivers of her hallucinating mind, analogous to the white slave owners claiming ownership and possession over the bodies of quadroon’s ancestors; despite being ushered to be relocated to Iberville—the suburbs of Edna’s mother-in-law. Mrs. Pontellier, unlike her husband, hadn’t the privilege of quitting the society of Madame Lebrun when they ceased to be entertaining. “She [Mrs. Pontellier] was only a bird in a gilded cage.” Readers perception of caged birds symbolic manifestation embody Edna Pontellier’s domestic enslavement, a reading reinforced by the balladry associated to the wedding of unfortunate dame with the wealthy master with some refrain. Mr. Pontellier was very fond of walking about his house, examining its various appointments and details, possessions he greatly valued, chiefly because they were his own contrasting in juxtapositional effect with Mrs. Edna Pontellier’s approaching the flowers in a familiar spirit and making herself at home with them. This analogy appropriates Edna Pontellier’s choice of her predilections and proclivities.

“How strange and how awful it seemed to stand naked under the sky! How delicious! She felt like some new-born creature, opening eyes in a familiar world that it had never known.” —-This quotable statements reechoes virginity and baptismal rites of birth of the holy Ghost as anticipated in her farewell from earthly life; as reciprocated in the self-authorized death. In other words, Edna Pontellier’s unfettered physical response to the sensuousness of the familiar world replenishes, renovates and regenerates herself. Dr. Mandelet thus, certifies the testimonial in the medical examination of nothing morbidity state but alleviated in repression from glance or gesture as exhortations point out, “She[Mrs. Pontellier] reminded me of some beautiful, sleek creature waking up in the sun.” However, in the penultimate liberality of the revelatory scene contrasts in juxtapositional effect of the “scene torture” in “with an inward agony, with a flaming outspoken revolt, against the ways of Nature, witnessed the scene torture” Adele Ratignolle’s physical labour of birthing, gestation, maternity and motherhood along with cultural labour of requisite image contextualize the femininity and womanhood. Adele Rontignolle’s speeches: “Think of the children, Edna. Oh, think of the children! Remember them!” the dialogism is precisely the abdicating of dispossession what she does as she evaluates the midnight vigils which follow. .

“She [Mrs. Edna Pontellier] meant to think of that; that determination had driver into a soul like a death wound—–but not tonight. Tomorrow would be time to think of everything […] There was no human being whom she wanted to be near her except Robert Lebrun; and she even realizes that the day would come when he, too, and the though of him would melt out of her existence, leaving her alone.” Edna Pontellier imagines the fantasy of romance and promiscuous cuckolding to be metamorphoses of ephemerality; re-imagines her struggles for emancipation and freedom, quest for individuality and selfhood and self-empowered fulfillment in a world of traditional roles and values as she is confronted with this dualistic battlefield between motherhood and extra-marital affairs.

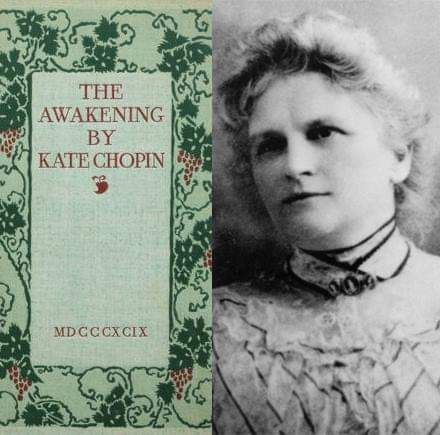

Kate Chopin’s autobiographical facetedness of stream of consciousness as a literary technique reveals the gulf experienced by Edna Pontellier’s inner world of private thoughts and rebellious emotions contrasted with outer world of self-censorship and self-containment and/or conformity. Presbyterian janus faced Kentucky stock was exposed to hypocrisy of weekday sins and Sunday repentance. Female passionlessness was hallmark avantgarde of the Victorian cult of true womanhood as reflected by Carol Gilligan’s exposition of feminist phallic power deficiency derivative in “the failure of women to fit the existing models of human growth may point to a problem in the representation, a limitation in conception of the human condition; an omission of certain truths about life.” …motherhood and womanhood…idolized their children, worshipped their husbands, esteemed it a holy privilege to efface themselves as individuals and growing wings as ministering angels.”

To Edna Pontellier bygone heroines of romance and the fair lady of dreams as embodied in the portrayal of Adele Ratignolle. Laissez-faire and free market enterprise or capitalism redeems the concept of femininity and maternity inseparable which exempts inclusion of female desire, autonomy or independent subjectivity. Motherhood imposes womanhood with societal conventions, familial obligations, stifling responsibilities and passive domesticity engendering double alienation resulting in the gulf of the traumatic estrangement from children and between the reality of her individuality and/or subjectivity.

References

Ivy Schweitzer’s Maternal Discourse and the Romance of Possession in Kate Chopin’s The Awakening, boundary2, Spring 1990, Volume. 17, No. 1, New Americanists: Revisionist Interventions into the Canon, Spring 1990, pp. 158-186