Chapter 19 – Day of the Dead, 1988

On the Day of the Dead Beverly kept to the routine she had begun a year after her mother’s death: she rose early, putting on her favorite pair of jeans and a blouse in the pale pink her mother favored. She took her baby picture from the closet, giving Clara’s image a quick kiss before tucking it into an inner pocket of her backpack. Then she spritzed herself with the Spanish baby cologne her mother had loved and walked out the door.

The holiday was acutely bittersweet for Beverly, marking as it did two milestones in her life. She had been born in the final hours of November 1; fifteen years later it became the day her mother died. But by the time Beverly turned twenty-five, her mother had been gone for ten years. She had mourned long enough; it was time to seek joy.

Her first stop was Ma Mon Luk, where she bought half a dozen pork buns, their ivory skins still sweating from the steamer. Her hour-long journey through the city grew progressively more cramped as more people squeezed into the elevated train and various jeepneys Beverly rode to reach Manila North Cemetery. It was mid-morning when she arrived at the edge of the wide river of people that flowed to the cemetery’s entrance, swirling around the security barriers police had set up to manage the crowds. Beverly hugged her backpack defensively against her chest, mindful of pickpockets but thoroughly enjoying the carnival atmosphere that infused the picnic-cum-vigil with which Filipinos celebrated their dearly departed on Araw ng Patay. Before entering the cemetery she paused at one of the many sidewalk stalls that sold candles and flowers. The candles hung from their uncut wicks like sausage links, flanking large tubs spilling over with chrysanthemums, calla lilies and daisies. Beverly took her time browsing before selecting one flawless shell pink rose and a white taper as long as her forearm.

“Yun lang – Is that all?” The vendor asked, smiling at the pretty young woman counting out her money.

“Opo Manang. It’s my mother’s tenth death anniversary but I can’t afford more than this.” Beverly offered an apologetic smile as she paid.

“Naku anak, the tenth deserves more than one rose.” The woman pulled out two red Gerbera and a few sprigs of Baby’s Breath, wrapping the modest bouquet in a page from an old tabloid. She handed the flowers to Beverly with a gap-toothed smile. “No extra charge. Just make sure to come back to me next year, ha?”

“Salamat po, Manang.” Beverly nodded her thanks before plunging back into the crowd. After Clara’s death, Beverly was often visited by the kindness of strangers, their generosity as delightfully random as butterflies landing on one’s head. Ninang ‘Cela said it was God’s way of making up for taking her mother away so early in her young life.

Security checkpoints marked the final hurdle before the cemetery gates. Crowds puddled around long tables where volunteers poked through every purse, basket and cooler confiscating plastic forks, metal nail files, crochet needles and anything that might even remotely have been conceived as a weapon. Like most holidays involving crowds with access to alcohol, Araw ng Patay carried the usual risk of drunken brawls. The police were determined to prevent spontaneous additions to the one million people already interred at Manila North Cemetery.

After passing through inspection, Beverly took her time walking through the roads that dissected the necropolis. She enjoyed mingling with these anonymous multitudes, imagining that they all belonged to one larger family by virtue of the sheer proximity of their dead. There were new visitors every year, but over the years Beverly had come to know some of the cemetery’s full-time residents, impoverished families who had transformed the necropolis into a rent-free suburb of Manila. She waved as she passed the makeshift school where, on regular days, Teacher Ipat gathered the neighborhood children around a blackboard propped up against the marble tomb of her mausoleum. After school hours the tomb did double duty as dining table and bed, and today Ipat sat cross-legged atop it, reading a dog-eared paperback. Down the road, the enterprising Aling Nening had converted her family crypt into a sari-sari dry goods store that sold everything from packets of laundry detergent to instant coffee.

Off to one side of the road, youngsters clutching their coins watched as a wizened vendor twirled a bamboo skewer round and round the whirring vat, magically spinning a pink cloud of cotton candy larger than their heads. The Day of the Dead always meant brisk sales for the living and ambulant vendors hawked duck eggs, barbecued pork and rice cakes up and down cemetery’s labyrinth of streets.

As Beverly drifted down the cemetery road with the crowd, she looked out for her favorite monuments, silently greeting each as one would an old friend. Here was the alabaster sphinx guarding a pyramid-shaped mausoleum, its caretaker wiping down the white marble with a soggy rag. Further along, the pergola that encircled a life-sized crucified Christ offered scant shade to a trio of old women flapping palm fans. In the distance she could see the weathered back of The Thinker eternally hunched atop his boulder, contemplating the section reserved for Jews. It was the only part of the cemetery not crammed full with visitors that day. A slight breeze riffled the leaves of the fire trees and shrubs, which softened the bleached landscape of limestone angels and marble tombs. Seeking relief from the collective heat of the shuffling masses, Beverly lifted her face to catch the wind.

Clara did not lie in this gracious memorial park but further out, in a humble section reserved for those who could not afford to buy an individual grave and all the sky above it.

Nearly an hour later, Beverly arrived at her mother’s final home: a microwave oven-sized niche tucked between many others in a five-story condominium for the dead, each unit identical to the next but for the birth and death dates that set the margins of its occupant’s life. Dozens of mourners were already there, chanting novenas, lighting candles and arranging flowers in small vases. Beverly nodded greetings to each of them. There would be time to chat after everyone was done with prayers.

Beverly unwrapped her humble posy and laid it upon the narrow ledge beneath Clara’s niche, then lit the candle, dripping melted wax to anchor it to the pocked cement. Standing back to assess her little tableau, she whispered the promise Clara had made to her at bedtime all through childhood: One day my life will be better. This was the one item of faith Beverly clung to, the closest thing to a prayer she’d learned from her mother, who had never been a conscientious Catholic. Without the anchor of traditional invocations, Beverly felt isolated and adrift as she watched families all around her murmur into folded hands. She glanced at her watch: it was half-past noon. With the heavy traffic, Beverly estimated it would be another two hours before her godmother arrived.

She was about to wander off to visit the larger tombs when little fingers tickled her arm.

“Happy Birthday, Até Beverly!” Tintin, the six-year-old daughter of Crescencia Jurado smiled up at her. She had lost two front teeth since the last Day of the Dead.

“Ay Beverly, happy birthday pala!” Tintin’s mother Cresencia walked up to Beverly, leading with her belly. A little boy in a grimy tank top and low-slung diaper toddled behind her. Crescencia’s family had lived in the same mausoleum for two generations, gaining a home in exchange for daily prayers for the soul of a realtor whose descendants had migrated to New Jersey. “Tintin still talks about the birthday cake you shared with her last year.”

Beverly had met Cresencia as a newlywed, but in the last decade she’d hardly ever seen her friend without an ongoing pregnancy or suckling infant. “Pang-ilan mo na ‘yan?” Beverly nodded at the woman’s belly. She could no longer remember how many children her friend had.

“Six if you count two miscarriages.” Crescencia sighed, her face prematurely aged by fecundity. “At least I know Nardo isn’t sleeping with anyone else – where would he find the energy?”

“Where do you find the time?” Beverly teased. Stooping to look Tintin in the eye, she pulled one pork bun out of her bag. “If I give you this, will you promise to share it with your little brother?”

Tintin skipped away, holding the pork bun high above her brother’s head, his cries disrupting the hum of prayers. Beverly watched Crescencia waddle after the two little ones, and hoped that the better life Clara had wished on her would include a daughter as adorable as Tintin.

Beverly was in the middle of adding a tall, attractive husband to the fantasy of her future life when a petite matron got up off her knees and tucked a plastic rosary into her purse. She whispered final prayers, bowing slightly to each of three niches, before turning to Beverly.

“Ay Beverly! Kumusta na ba?” Alfonsa Pison had tended the graves of her parents and twin brother for decades and was an old hand at caring for the newly bereaved. She had been making her weekly visit the day Clara’s broken body was laid into the niche next to her own mother’s a decade earlier. When Marcela and Beverly became too distraught to deal with the laborers, the spinster had overseen the rest of the work, placating the two mourners with coffee and boiled eggs.

Now Alfonsa looked Beverly over, her gerbil-like nose twitching from perennial allergies. “You look like you haven’t had breakfast. Heto — this pan de sal was made fresh this morning.” She held out a bag of rolls, urging Beverly to take some. “You look like you’ve lost weight. Are you in love?” Alfonsa’s large eyes twinkled above a raisin-sized mole perched on her right cheekbone. “Who is your novio?

“Wala. I don’t have a boyfriend.” Beverly blushed, anticipating the usual jokes about her uneventful love life. “Mama taught me not to trust men, you know.”

“Hija naman, they’re not all bad,” Alfonsa clucked. “All you need is one good man —“ A minor commotion at the far end of the columbarium stopped her mid-sentence, her small mouth forming a startled ‘oh.’ Turning around, Beverly was startled to see a vaguely familiar girl smiling as she walked toward them. The girl wore a canary yellow sundress and silver hoop earrings and carried a sheaf of long-stemmed roses in one arm like a newly crowned beauty queen.

“Diós me salvé – God save me — can it be?” Aling Alfonsa whispered. “Yes – it’s Lisa, Lisa Patané.”

The girl in question had been orphaned seven years earlier, when her parents had perished in an apartment fire. Their charred remains had been buried together in an extra wide niche just above the one that Clara occupied. Like Beverly, Lisa had been forced to drop out of school and find a job after the tragedy. The two orphans had quickly bonded and Beverly looked forward to their annual reunions, when the irrepressible Lisa would spend hours describing her latest romantic escapades.

Today Lisa seemed different — regal, almost. She sauntered forward, not needing to excuse herself because people stepped aside to gawk at the man who followed in her wake. The grey-haired foreigner stood a head taller than everyone else, long of chin and short of neck, mirrored sunglasses perched on a bulbous nose. As the couple neared, Clara noted the sweat crescents that darkened the armpits of his Hawaiian shirt, the Bermuda shorts that bared thick calves covered in pale fur. She wondered where Lisa, who hawked cosmetics six days a week at Shoemart, could possibly have met him.

“Behhh-ver-lyyyyy, long time no see!” Lisa’s voice was higher-pitched than usual, her English broadened by an accent Beverly only heard in American movies.

“Kumusta na, Lisa?” Beverly greeted her friend, insisting on Tagalog. “Who’s that old man? Was he a friend of your parents?”

Lisa’s giggle pealed like a church bell run amok. “Of course not! Ikaw talaga–” Lisa pinched Beverly’s arm, switching to Tagalog as well, “You know the ‘kanó– they always look older than they really are.”

“Honey, what did we say about talking TAG-alog when I’m around?” The man’s tone was petulant.

“Honey naman, it’s so hard to do that when we’re in Manila.” Lisa offered the man a pout, her crimson lips just level to his chest. “Don’t you worry love, when we get to America, I promise to speak English all day every day, just for you. ‘Kay? ” As she winked at Beverly, her eyeliner left a blue smear upon her cheekbone. “Beverly, I want you to meet my fiancé Lydell Kinkade the Third.”

“Fiancé?” Beverly could barely hide her disbelief. How could Lisa have so quickly found a novio willing to provide the happily-ever-after ending Clara had promised? Did her two dead parents pull greater weight among the gods than her never-married mother? “You didn’t even have a boyfriend when I saw you last year.”

Lisa shrugged, slinging an arm around the Lydell’s hips. “When it’s true love, there’s no point waiting. Right, hon?” She looked up at Lydell, who puffed out his barrel chest.

“You betcha, sweetheart.” Lydell jerked his head at Lisa and clicked his tongue. “This here’s m’girl. I knew it the minute I saw her standin’ there, holdin’ all my letters tied up with red ribbon.”

“Lisa talaga.” Beverly grinned. “You stole that trick from an old Sharon Cuneta movie, didn’t you?”

Lisa let out a delighted yelp, and for the briefest moment reverted to the giddy teenager Beverly remembered. Recovering quickly, she chirped, “Beverly’s being silly. She thinks magic only happens in the movies.”

Lydell took off his glasses, looking Beverly over as though she was a used car. “I wish you’d told me you had such pretty friends, Lisa. I would’ve brought Hank along on this trip.” He leaned close enough for Beverly to smell the mint in the gum he chewed. “My friend Hank’s newly divorced too. Could’ve been a love match!” He smiled, flashing teeth the color of weak tea.

“Ay sayang!” Lisa waggled her eyebrows at Beverly. “Never mind, once I meet this Hank in Naples I’ll tell him to start writing you.”

“That’s Naples, Florida to you.” Lydell made the clicking sound again. “Wouldn’t want people to think I was some kinda Mafioso.” He chuckled at his joke while the women traded puzzled glances.

Beverly stared at the oddly matched couple. Lydell looked to be twice Lisa’s age and more than double her weight, and yet she had never seen her friend so ecstatic, nor for that matter, so vividly made-up. Plum rouge drew cheekbones on Lisa’s round face, and her crimped eyelashes glinted indigo in the morning sun.

Quelling her skepticism, Beverly asked, “So how did you meet?”

“We were pen pals for six months on Filipina Sweetheart. Then he came to visit three weeks ago and it was instant magic. He took me to dinner, bought me flowers, he even chose this dress for me. Can you imagine?” Lisa gushed. “And it was so easy — I gave my pictures to this international dating service and in two weeks, I got letters from three different men.” She batted blue lashes at her beau. “But Lydell’s letters were special. He’s a stenotype reporter. At court, you know. Stenotype reporters have to write all the time.”

“Wow.” Beverly fixed a smile on her face, unsure what exactly a stenotype reporter was. “So when’s the wedding?”

“We have to do it in Florida. I wanted sana to have a church wedding here, but it’s too complicated. Did you know you have to ask permission from the Archbishop of Manila to marry a foreigner?”

“It’s like you Catholics never left the Middle Ages.” A sunburst of laugh lines deepened around Lydell’s green eyes. “ ’S’why I’m Mormon.”

“Just like Donny and Marie Osmond! You know, Lydell promised he’d take me to Utah one day. Can you believe it?” Lisa squeezed Lydell’s arm, her nails like cherry lozenges on his papery skin. “After he proposed, the agency took care of everything, including my fiancée visa. I quit my job so I could show Lydell around the country before we leave. You know, when Lydell asked me to marry him, he showed me pictures of his house in Florida. Biro mo, it has three bedrooms, two bathrooms and a big living room! One bathroom even has a whirlpool tub. There’s a big garden in back and a lawn out front…I could get lost in that house.” Lisa leaned her head into Lydell’s shoulder, oblivious to the snickers of bystanders who’d abandoned prayers to eavesdrop. “I can’t wait to see it.”

“Suwerte mo naman, what luck. It sounds like you’re moving into a palace.” Beverly was surprised at the sudden pang in her gut, as she thought of the tight bedroom she shared with her roommate, the mouldy shower stall, the roach-infested kitchen. “When are you leaving?”

“In two weeks. This is the last time I get to visit Tatay and Nanay until we come back to Manila. Who knows when that will be? Oo nga pala, I brought this for them.” Lisa looked at the narrow ledge below her parents’ niche as though seeing it for the first time. “Oh but honey, our flowers won’t fit on that small space! What should I do?”

Lydell scratched his hairy nape, unconcerned. “Figure it out quick so we can leave. This heat is making me thirsty.”

Lisa stood the bouquet on the ground and propped it up against the wall of niches, accidentally knocking over Beverly’s candle.

“Hayaan mo na — leave it alone, I’ll fix it.” Biting her lip, Beverly pulled her mother’s modest posy out from behind Lisa’s roses, then re-lit the candle on the farthest end of the ledge. Clara’s niche seemed to recede in the shadow of the gargantuan bouquet.

“Beverly, favor lang, can you take our picture?” Lisa waved an instamatic camera, pulling Lydell to the side of her parents’ niche. “This is the closest I’ll get to introducing Tatay and Nanay to Lydell. Sayang they didn’t live to see this. They could have come to America.”

Beverly peered through the camera lens, motioning for Lydell to stoop so that she could fit both faces in the same frame.

“Say green card!” Lydell teased. Lisa giggled, baring lipstick-smeared teeth.

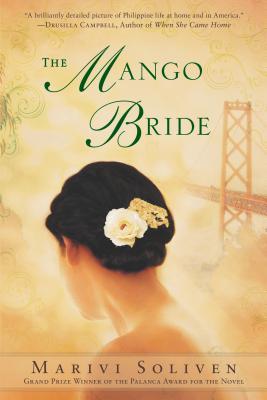

Marivi Soliven is a Filipina author based in America where she works as an interpreter. Her background as a writer includes having taught creative writing at the University of the Philippines, the Ayala Museum, and the University of California in San Diego.