Chuck Taylor, Fever. Slough Press: Austin, Texas, 2024. 195 pages. $24.95. ISBN#9798866760268.

Reviewed by Janet McCann

A poetry book that you can’t put down is hard to find, but Fever qualifies. This collection shows how it felt to grow up as a boy in the mid-20th century, and then to live in the drastically revised world of the 21st century and encounter all the new definitions and expectations.

The title poem pulls the reader in with its couplet form that provides long expository loops and close-up scenes. The book is like a river, running on and on and over rocks and around obstacles. The inner and outer landscapes are fresh and appealing. The reader is carried along, and now and then there is a bright stone, or perhaps a glimpse of something frightening under the flow, and always there are startling insights.

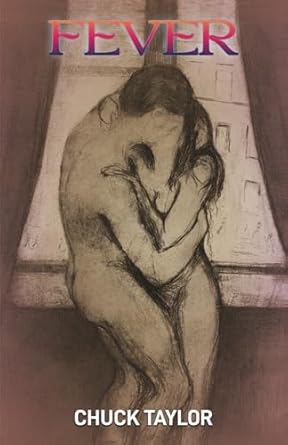

Chuck Taylor is a veteran poet, prose writer, and photographer who taught Creative Writing at Texas A&M University for many years and has published dozens of books. This is an especially attractive volume, with Munch’s nude couple embracing on the cover and brush drawings throughout by the poet himself.

More than half the book is the first section called “Fever”, which describes the growing up of Vance, who has a somewhat rocky upbringing in the mid-20th century with a neglectful but demanding mother and a quixotic father. From there, Vance enters the adult world and has adventures which will form him and push him somewhat off the grid forever. Sexual discovery and identity evoke smiles and winces. Young Vance reads Augustine of Hippo, who found sex “the original sin”:

…sex is the fall

from grace, from the garden where once the lion

and the lamb lay down together, into the

toil of soil, the thorn of roses and

the blood and pain of baby birthing; sex

passed from Eve and Adam, worm slithering

dumb into our operating systems

at around twelve or so, starts maddening

dreams, hijacks souls and bodies, and makes us

do what God in nature wants—populate

the Earth to choking; forget ideal dreams…

…Yearn instead for naked

skin, for bare ass; the virus has grabbed our souls…(20)

“Fever” is written in a kind of flexible blank verse, ideas strung together, thoughts leaping over the rhythms.

Other sections include “Taking Off,” “Takeoffs,” and “Lizard King.” “Taking off” narrates stories of the young man completely escaped from this constrictive home, and what he learns through his first individual experiences. The last section is “Lizard King,” which is dedicated to John Morrison, and it is an unusual poem that has only one word per line. The poet pleads with us to slow down in the reading, but this is hard to do.

“Taking Off” gives glimpses of many kinds of prisons, including age. The “Lady of the Pink Slippers” wants Jack, visiting his resident mother, to open the glass door of her care home and release her. But he can’t—the door is so constructed as to prevent its opening. He muses on prisons in his own life, then ponders the

lady of pink slippers who we

muse, we dream, must surely

be given, most definitely, the

right lucky chance, given

a great maverick moment—

though tired, though busted,

though beatific, though beat—

to wing with us on through

doors across fields into the

long various grasses of freedom. (99)

These poems attempt to define the relationship between men and women, physically, socially, and emotionally. The main characters growing up this during the period of rapid change in values in the understanding of sexual and gender roles, gives a unique perspective on these changes . I often wondered how the young men I knew fifty years ago managed to accommodate the difference in expectations. Reading the poems, I can feel what a young man felt, and know what he learned as he aged.

The concluding section, “Lizard King,” the poem of one word per line, is not amenable to quotation. But the third section, “Takeoffs,” is most entertaining. “Takeoffs” gives meditations, ideas, and images based on other literature, sometimes in the form of imitation. They may be serious or laugh-out-loud funny. He kindly gives us the William Ernest Henry “Invictus” so that we can fully understand Taylor’s version “Inlustus,” which follows it. “Inlustus” concludes:

Beyond this place of peace and grace

looms a filling Mexican dinner plate,

and the candlelit pleasure of your face

in the afterglow of our randy state.

It matters not how cold the side dish soup,

how greasy hot the plop of refried beans,

you are the dizzy center of my loop,

I am the gleeful nibbler of your greens. (141)

Fever demonstrates the need for freedom and the various traps and prisons we find instead: sexuality, other confining elements of the male role, societal demands often based on sexual expectations. And it shows us a side of male experience not so often explored. This is a collection to glide though and then return to.