Kill Me!

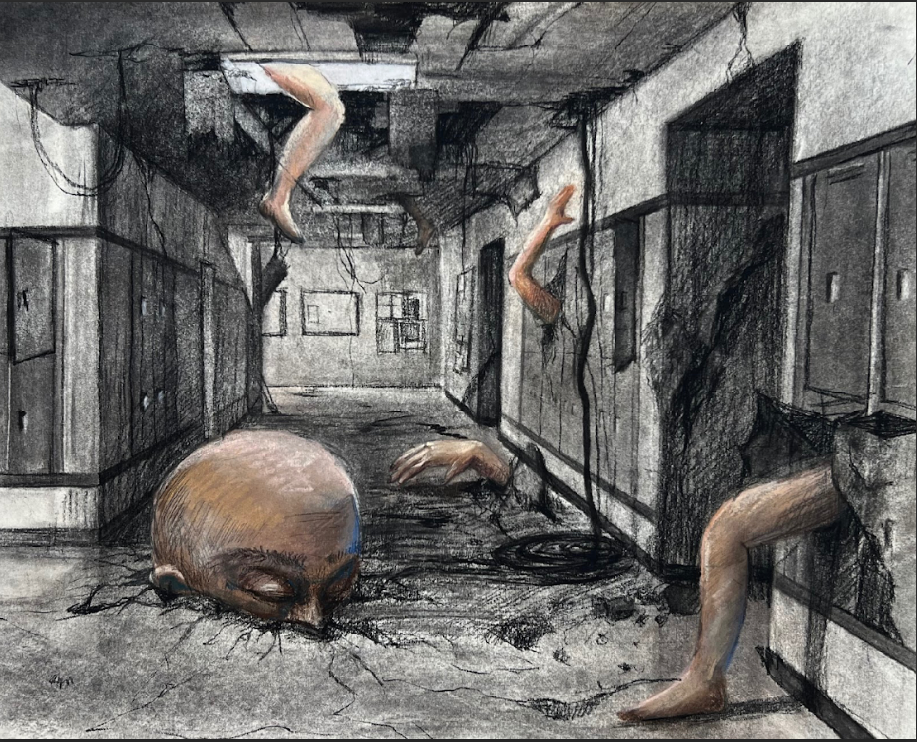

He hung upside down on an aluminum frame bed, my friend Victor at the Austin Seton Hospital. Sores covered his body. The nylon straps that held him in place didn’t touch many sores and were supposed to make it possible for most to heal. Victor was on morphine drip for the pain.

The man had grown up in a poor aristocratic family in Mexico. His father had a small hacienda that he sold soon after Victor grew up. Victor figured America might be a better place for a man that loved the study of philosophy. He drove a taxi in Austin for Roy’s, but spent the majority of his hours at the philosophy table in the UT Student Union arguing existentialism and the absurdity of life. Victor carried worn and fat Spanish translation of Jean Paul Sartre’s Being and Nothingness. He had a rubber band around it to hold the book together.

My former wife Brenda kindly provided him a room to live so he could get his act together, but after a year she told him he’d need to leave. He ended up living in a tiny one room place in Clarksville neighborhood and that’s where the sores developed. He was not taking his insulin for his diabetes, not bathing, and not eating much. Victor ignored the sores and never went to the doctor.

Victor was tall, thin, bearded and neurotic like I was. We both looked like we stepped out of a Woody Allen movie.

So now Victor was hanging upside down at Seton Hospital. I had come to see if I might help. I sat in a low chair next to his bed, bent over, my head turned up as much as possible to see and talk with him. It was not a position I could maintain. I saw in his face the befuddlement and despair, now much worse because of the pain.

Victor had been married to a hippie American woman who had renamed herself Miracle. I met her once. She was trying to make a living growing and selling wheat grass. For a short while wheat grass was the miracle food to save the planet. They had a daughter named Star who lived with Victor and was tall and blonde like her mother. Star tried once to get me to write a high school essay she needed to turn in the next day. His former wife had more difficulty surviving than Victor. She had transferred daughter Star and son Daniel over to him to bring up.

A year ago the daughter had gone on her first date. The boy took her for a ride through the lovely Texas hill country. The car did not complete a turn and went off a high hill into a deep valley.

Both these beautiful seventeen-year-old children died. I remember Star’s funeral under a canopy in the September heat in a Round Rock cemetery. It was called a celebration of life.

The son Daniel was too broken up to come to his sister’s funeral. The boy was just a sophomore but a star player on the Austin High’s soccer team. The father had found the Clarksville apartment so his son could go to the best public high school in town. How they all fitted into that one room apartment I can’t imagine.

Victor looked down at me as I tried to look up at him. For a long while he did not speak, then he said quietly, “Kill me.”

I jumped up from the chair I sat on and moved toward the door. The words struck deep. To lose a child was the worst thing that could happen to anyone. Victor’s chances of surviving I’d been told were poor. I wanted to help. We had spent a lot of time talking together down at my bookstore. I knew he was poor and didn’t mind that he never bought anything. Sometimes he’d bring me a cup of coffee. This was around 1982 when downtown Austin was being torn up. Sidewalks were widened, parking spaces were decreased, and trees were being planted along Congress Avenue. Flagstones were replacing the old sidewalk concrete. Changes were in the air. The Austin I knew and loved was beginning to become something else, a place not for intellectuals like Victor and I, a computer place that would soon be full of libertarian millionaires.

But then I saw a flash arrogance on Victor’s face, followed by a touch of delight. He was testing me, pushing me. He felt a certain power. Victor wanted me to cross a terrible moral line and did not seem to care if it would haunt me forever.

“Kill me, please,” he repeated, even more intensely.

What was there in the room to kill him with? He wasn’t plugged into any machine I could turn off. The nurses would call the police. I’d be arrested. I could spend a long time in jail. I might even be executed.

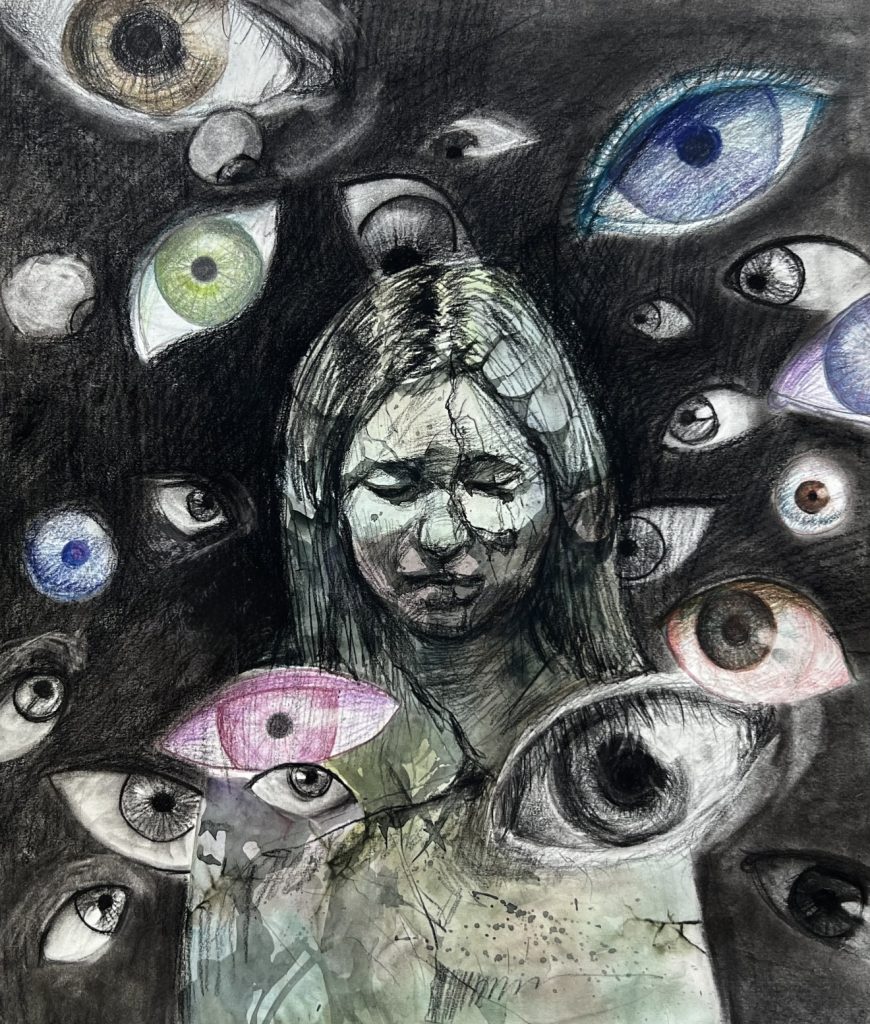

I sensed he was enjoying the game, even in his awful pain. I looked up again to where Victor was hanging and saw for a moment the body of an alligator. His head was an alligator’s head with big grinning teeth.

“No,” I finally said. “I can’t. You could recover.” I started crying, got up and walked away again. I was crying for Victor and for myself. I was crying even for the alligator.

I’d been living in the bookstore’s basement on four hundred a month for over a year. Roaches would come down the hall from the sump pump and crawl onto my legs. I did not own a car. It had taken me an hour to walk to Seton Hospital on a cold November Sunday while my wife worked the store.

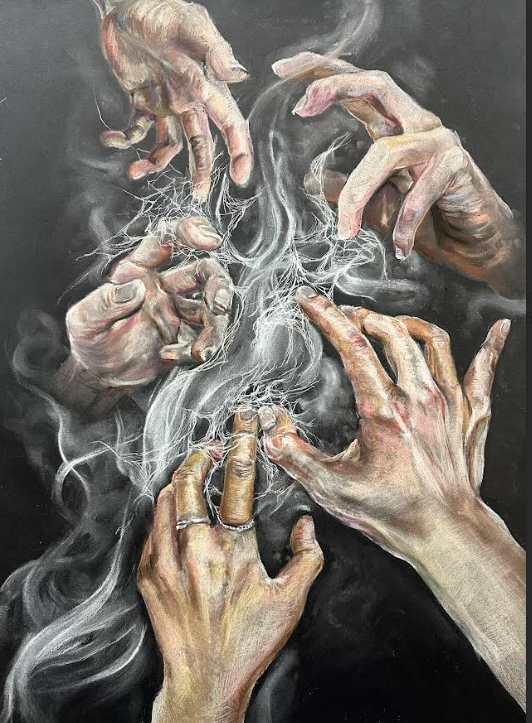

On the way back to the bookstore my rebellious mind started whispering, ‘What would Jesus have done? Could Jesus love a man enough to kill a dying person if asked by the dying person?’ I thought of Sunday school as a ten year old back in the suburbs of San Antonio.

No, I decided. Jesus had died to save all humankind, not for one person. Jesus would have healed Victor’s sores. Snap. Just like that.

Too bad Jesus wasn’t around now.

I was no longer close to Jesus, but we did talk now and then, especially as I was drifting off to sleep.

Victor died two months later while on a private plane flying back to Mexico. He was asleep and slid into death in spite of the pain.

I try to focus on the good times with Victor down at the bookstore, on our great conversations about absurdity and how to make a good life, as we waited for a customer to come in.

It’s twenty years later now. I moved to Chicago ten years ago to manage computers for Chicago Trust Bank. I remain a little guilty I didn’t do what Victor demanded. I could have relieved his terrible suffering. Maybe the arrogance and delight I saw in his face was not there. Maybe my mind wanted to see those things in order to get me out of the situation. The alligator, after all, wasn’t there.

I don’t understand the tragedies of this world. I fear the alligators and understand why people turn to Jesus. Onward I say, through the guilt! Find the pleasures life can give. I am married now and have two children.