Over 200 years ago, William Wordsworth thought poetry was “emotion recollected in tranquility.” More recently in “An Argument with Wordsworth” Wendy Cope has observed that while there is plenty of emotion to go around, “there’s a serious shortage of tranquility in which to recollect it.” (Cope’s poem is included in a collection of responses made by female poets to male-dominant perspectives over time—The Muse Strikes Back: A Poetic Response by Women to Men, eds., Katherine McAlpine and Gail White, Story Line Press, 1997). In many volumes of fine poetry Carol Smallwood has taken up the challenges faced by poets who wish they could eek out at least some tranquil time, and she has found great power in her observation of everyday experiences. In her latest collection, Patterns: Moments in Time, she not only stirs powerful emotions but fulfills Wordsworth’s famous goal to present “ordinary things” to the mind “in an unusual aspect.” Smallwood’s poems re-create ordinary events, places, and experiences for her readers who then find or make even more new patterns through closer observation and sharpened imagination.

The structure of this collection bookends the variety of the many ways it is possible to see in fresh ways what we already experience nearly every day. The Prologue sets the stage for how even a day’s most monotonously ordinary events can be imprinted with fresh and lasting imagery. In “Driving into Town,” pine trees that have fallen into snow become “filled green cellophane toothpicks/ next to slim bare-limbed trees/ as if at a cocktail party” (17). Will that allow you to take an ordinary drive without perking up ever again? Nothing fancy on this morning drive or in the stop at the car wash where a routine customer becomes a “strange woman driver” and “green hula girl plastic strips rotated/ warm water streams each side the/long empty fogged car wash tunnel’—at last tossing the car out of the tropic back into the snow “to make a solitary track of white” (23). Routine car washes are over. “Grandmother Said” transforms the most routine needle-and-thread hours into creative energy that renews the earth. The oldest doll in the collection, Betsy is “entirely fine” as she sits resiliently for so long “as an anchor and a lifeline” (89). The penultimate poem in the volume, “Rain Began Hitting the Window,” begins by quoting T. S. Eliot’s “Four Quartets”: “We shall not cease from exploration, and the end of all our exploring will be to arrive where we started and know the place for the first time.” With memories flooding in, the rain brings the speaker closer to the knowledge and acceptance that we will become part of the soil we love with Aunt Hester who would “see I wore Clorox-clean underwear” and Uncle Walt who would somewhere still be saying “I got a wife who would bleach the hell out of the robes of God Almighty” (99). Of course the earth spins, the wind blows and the house wraps itself around all that is folded into the earth—and it all comes back around again as if new: “As part of the soil—my exploration just begun, I’d know for the very first time” (100). A prototypical pattern of whirling cumulus clouds brings the challenge of the “Epilogue” to choose one cloud “to secure the secret of time and space” (103).

Formally, the villanelle is the perfect poetic pattern to circle around and back to the place one started: renewed, surprised, refreshed. Repeating rhymes and refrains set off on a quest that meanders through new places, yet winds its back at the starting point with the freshness of shifting perspective and context. It’s the persistence and musical patterns that “language” their way to penetrating insights while always seeming to circle back and yet deeper into what is seen and felt to be effervescently fresh. “A Villanelle for Betsy” is vintage Smallwood. The poem revisits a very old doll with a cracked head who, we learn, has been for some time “an anchor, an unfailing lifeline” (89). She sits patiently through all. She sits proudly through the patterns of repetition that reinforce resolve that is known to be “entirely fine.” “The Wonder Spot” examines an educational tourist spot unlike any other on earth that takes us beyond school bringing change that we become convinced is “undeniable” (29). Another breakthrough to what is remarkable in the mundane is “Grandmother Said” where the best uses of a needle and thread turnout to be staving off loneliness (69).

The villanelle follows rules exactly as does “the way to row” in a “tradition set long ago” (21). Without any doubt “It is the Rule,” (“A Matter of Rowing,” 21). Ambiguity receives its charge from understanding through rules “how many ways” something can be read (“Ambiguity,” 87). “Hopscotch” where the chalk marks seem indelible, impervious, defies the rules swishing forward “with no thought/of rain—or tomorrow” (48). “A Mainstay” holds on to the rules of hard-cover book publishing, now challenged for so long and ever widely by new forms. Asked because its girth and weight almost no longer fits if the volume is her bible, the speaker treasures her disheveled work of art, pining that “all books would last, match the quality, continue a mainstay´(19). Some rules even bring comfort, and when disturbed anxiety follows. “A lack of sleep encourages awareness in the safety of predictability,” the wise speaker reflects; there is fear of the unknown and worries about civility and predictability and a new respect for all that we take for granted—appreciated most when threatened or disrupted (“Safety of Predictability,” 68). In one more example, a trip to the grocery store celebrates the defining powers of counting and naming in adherence to or defiance of the ubiquitous rules. Not everyone pauses to observe “which aisle had the strongest overhead fan,” how many brands of Extra Virgin Olive Oil there are to choose from, or feel like an honored guest given precious “time to bask among the plastic plates, marshmallows, and feel proud” (“Shopping Today, 96).

Most of Smallwood’s collections of poems have suggested ways that we can experience more fully what happens just about every day. More than any other, this book looks to individual moments in time to explore the processes through which we recognize patterns already there, create new ones through creative sensibility, and learn how the processes of engagement make us more alive. Quilting pieces recall earlier moments and then themselves become new moments in “a war fought by women with a needle” emerging as a new creation “the next day fresh as a primrose” (“Shallow Boxes,” 27). The book’s Midwestern roots win out as the moments are meant to savor the essence of each seasonal change, building memories that create pattern (“The Seasons,” 40). Savor also the ambiguity of trees “reflected upside down in puddles on my way to school” or puzzling over the syntactical puzzle of how many ways we can read “Sam blew up the door” (“Ambiguity,” 37). Does it matter, many of the poems ask. Are the patterns already there, wherever “there” is, or do we make the patterns “there” or later through memory and imaginative reshaping? It matters in “Stop Look Listen” when a “sleek red car with large letters NASCAR” turns out to be “NURSECARE with someone flicking a cigarette out the driver’s window” (26). Memories of the nun who uses nonsense to retool becomes profound through proud incantation: “I recall it” (“An Unlikely Introduction,” 41).

Moments in Time is an unobtrusively great book that will sneak up on you, wear well on the coffee table, stay with you, and change the way you experience much that happens every day. Smallwood springs us from some of the traps even good writers and readers can fall into. In Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance, Robert M. Pirsig has suggested in a well-known quote: “We take a handful of sand from the endless landscape of awareness and we call that handful of sand the world.” The poems in Patterns would be happy if we were grabbing any sand at all instead of dozing, but each poem asks us to look closely at what the sand is, how it got in our hands, and how and why we name it the way we do.

This large and roomy collection never loses its focus on the many ways we make moments in time that flourish in memory and last a lifetime. In “Select Moments,” the speaker lies flat in the making-angels-in-the-snow position feeling for movement in the rhythms of life itself, hoping for clues to “what it was all about” and trusting that the moments would make sense: “Surely if I stood tall as possible/ Long enough, tried hard enough/ there’d come hints, some pattern.” And so this long and packed volume meanders patiently to the prologue of cumulus clouds where a focus on one single cloud hopes to “secure the secret of time and space (103).

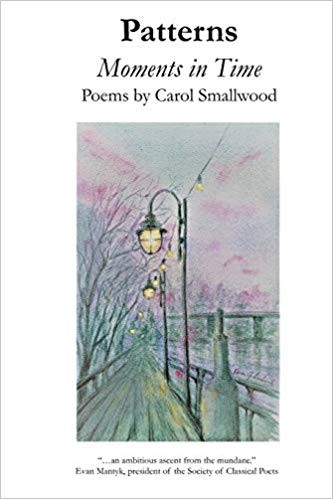

Faults in the book? Always—but maybe just flawed enough to secure the genuine aesthetic pleasure that requires some imperfection. The collection might be repetitious at times; some poems maybe try too hard. Long time Smallwood fans might be disappointed that some poems are reprised from early publication. But the moments that wobble also become part of the haunting and satisfying patterns we carry with us from our reading. Puzzlement, ambiguity, surprises, and the ordinary stuff of an otherwise sleepy afternoon—everything feels just a little less ordinary. The structure of the collection matches the unfolding of renewal steaming out of memories. The feel of the book in one’s hands seems right, the typeset and pristine editing, the soft beauty of the cover design—all these are the work of a Lifetime Achievement Award winner who has much yet in the making.

Ronald Primeau

Professor of English Emeritus, Central Michigan University

Adjunct Instructor, University of South Florida Sarasota-Manatee

Carol Smallwood’s Patterns: Moments in Time is available from Word Publishing here.