For someone who enjoys a great story, is there anything better than a narrative that engages you from the very start? Imagine a world so rich you can almost smell the scents in the air, a delivery so clever it forces you to think in a way you never thought you would. I’m Ryan J. Hodge, author, and I’d like to talk to you about…Video Games.

Yes, Video Games. Those series of ‘bloops’ and blinking lights that –at least a while ago- society had seemed to convince itself had no redeeming qualities whatsoever. In this article series, I’m going to discuss how Donkey Kong, Grand Theft Auto, Call of Duty and even Candy Crush can change the way we tell stories forever.

What the arcade teaches us about changing the rules of a story

Now, I’m sure even those who would consider themselves ‘out-of-touch’ with the games industry can appreciate that the boxy, awkward ‘electronic babysitters’ of the 70s and 80s can’t hold a candle to the cutting edge graphics and Hollywood budgets of modern games. You’d probably think I’d gloss over the days when the industry was in its infancy, but those developing years were just as crucial as the current ‘console generation’. For it was in this chaotic time that the most critical aspect of game design was discovered and honed: paradigm shift.

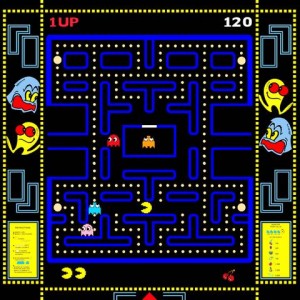

What makes us care if Pac-Man escapes the ghosts or if Mario rescues the princess? If someone were to write these stories as is on paper, they’d probably be pretty dull; just an endless series of munching dots or stomping Goombas. Yet players would remain in front of their screens, transfixed for hours; dumping their (or their parents’) hard earned money into an experience that doesn’t matter, is not particularly complicated, and has no real application or parallel in the outside world. From a pure surface level, it makes little sense why the ‘Arcade Classics’ took off, and even less in terms of how it can be applied to contemporary narrative.

But there is actually something beneath the surface; a primal appeal to the human psyche that any good story teller would itch to exploit. In traditional sports or board games (as opposed to video games), there are certain rules or logical progressions that have to occur in order for the game to be ‘fair’. In narratives about such events, the focus generally is around the ‘players’ mastery of self and spirit in order to succeed within the confines of these rules. While sometimes the ‘rule’ dynamic is changed (due to an antagonist cheating to some degree), the narrative is very rarely centered on learning and mastering the ‘rules’ themselves.

While a static rule set is also technically true for video games (after all, they have to be ‘beatable’), what makes video games unique compared to other modes of play is that ‘the rules’ themselves are not always communicated to the player from the start and sometimes new rules are added on the fly. The player investment comes from learning these rules and how to apply this knowledge to beat the game. That is the paradigm shift.

To be clear: this isn’t relative to basic instruction (i.e. move the joystick in the direction you want to go to move in that direction), I mean that the recognition of patterns are not explicitly stated anywhere, but still exist all the same. Take Pac-Man, for instance. The only rules explicitly communicated to the player are that he has to move around the maze to collect all the dots while avoiding all the ghosts. What the player isn’t told is that each ghost has a different behavior pattern. The red one will always chase him, the blue one will try to get in front of him, and the orange one moves at random. Playing without this understanding will only get the player so far but mastery of this concept is crucial to long-term progress.

What does this have to do with narrative? Well, I’d like to direct your attention to John W. Campbell Jr.’s Who Goes There? (1938) which readers might better recognize from the 1951 and 1982 film adaptations The Thing from Another World and John Carpenter’s: The Thing respectively. Hailed in many circles as an exemplary specimen of SciFi Horror, the conceit of this story is that some type of alien ‘intruder’ has infiltrated an Antarctic research station. It accomplished this infiltration by mimicking the form of a sled dog and, later, members of the research team. Once the intruder has completely copied its target; it appears to be a perfect imitation with complete mastery of language and social nuances (as opposed to, say, a ‘pod person’). The entire story is the conflict surrounding how to discover and ‘deal with’ the intruder, which is accomplished by the research team slowly learning about its nature (i.e.: its ‘rules’). First they learn that the intruder exists, then, that it can copy people as well as dogs, then that every cell of the intruder organism is its own semi-independent life-form (meaning that if you chop its head off and burn the body, the head will grow legs and skitter away).

What separates this story from a distressing amount of horror narratives is that the characters within it never do anything stupid. They never deliberately put themselves in danger (mental breakdowns notwithstanding); rather they develop a theory about how the organism works and apply protocols commensurate with that theory until a new fact (or ‘rule’) is revealed. Now, this may seem obvious; but consider how few stories even accomplish that much. Compare Who Goes There? to Prometheus (2012 Film) where so-called scientists must perpetrate nonsensical breaches in basic safety protocols (removing helmets in an alien atmosphere, making kissy faces at a beefy alien cobra analog, etc.) just for the plot to even happen. What was meant to be a thrilling story of danger and discovery becomes an unintentional comedy of errors.

Sometimes the lack of effort is more blatant than that, wherein we see narratives that include some combination of chainsaws and hapless teenagers.

Humans thrive when we have an understanding of things, but all drama is lost when we, the audience, have solved the problem long before the characters in the story. What keeps a story fresh is either a changing of an established dynamic or a dynamic whose true nature remains elusive.

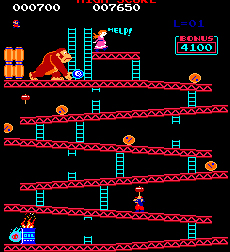

But far more can be learned about narrative from the supposedly ‘storyless’ early video games. For in addition to themes of obscuring rules, players were also forced to prove their mastery of core gameplay, but in different ways. For these examples, we will consider the Mega Man series and Donkey Kong series.

I’m cheating a bit here given that these were console releases and not arcade classics…and you’re just going to have to deal with it.

In these games, players are given a core set of actions with which they must traverse an expansive and diverse level set, however the two go about this in different fashions. Mega Man demands a mastery of player tools…

…where Donkey Kong demands a mastery of environment.

In both games, techniques that were linchpins of previous levels will not always be useful in the next. Further, in these games it’s literally ‘adapt or die’, as failing to master the techniques required to pass a level with result in the player character’s untimely end. The hook is learning when what approach is most useful. As such, the player’s mind and reflexes are sharpened and the game itself retains its difficulty, no matter how masterful the player is at the controls.

So how do we tie this back to narrative? Well, a sure way to raise dramatic stakes is to place your characters in a situation where everything they’ve learned or applied previously is absolutely no help. One of my personal favorite examples of this is Isaac Asimov’s Foundation trilogy (1951-’53). In these stories, Asimov plays with numerous psychological themes as its protagonists are challenged by the fear of the inevitable and the fear of the unknown. In all cases, it is not pure physical superiority that wins the day (in fact, brute strength is the downfall of many of the antagonists) but the mental agility required to solve each unique problem in its own unique way.

It is so easy for writers in any medium to rely on a protagonist’s (or antagonist’s) previously defined attribute to carry a story (not to mention a sorry recipe for gaming). By challenging a protagonist, or player, to deal with change or to do without; the dynamic of the story itself becomes more interesting.

A swordsman may lose his hand.

Or a special power can be taken away from the hero.

There are plenty of stories that already do this, and if you’d like to sort them from the bevy that don’t; be my guest and happy hunting. However, beyond the dialogue and characters, there exists a core experience that can be distilled not through words, but through action –through play. In order to feel as your protagonists would, to think as they must to overcome new obstacles; loading a catalog of Arcade Classics on your phone or tablet, picking up a DS, or dusting off your kids’ old Nintendo just might provide some valuable insight. And who knows? It just might make you a better writer.

Ryan J. Hodge is a Science Fiction author and Lead Writer & QA Manager for Konami Digital Entertainment US (SF Office). His latest book is Wounded Worlds: Nihil Novum, is available now for eBook & Paperback.

Media

The Last Airbender: The Legend of Korra (2012) Nickelodeon –TV

Donkey Kong (1981) d.p.Nintendo -Arcade

Donkey Kong Country (1994) d.Rare. p.Nintendo –Super Nintendo Entertainment System.

Foundation (1951) Isaac Asimov, Gnome Press

Game of Thrones (2011) HBO -TV

Mega Man (1987) d.p.Capcom –Nintendo Entertainment System

Pac-Man (1980) d.Namco p.Midway -Arcade

The Thing from Another World (1951) RKO Radio Pictures

John Carpenter’s: The Thing (1982) Universal Pictures

Who Goes There? (1938) Joseph W. Campbell Jr., Astounding Stories

Very deep, well researched with personal experience. Very nice.