My Second Home, Basa Village

The first time I went to Nepal it was 1995 and I was amazed and bewildered by the cultural potpourri of Katmandu. The drive from Tribhuvan International Airport to the Mustang Hotel was a moving feast of color, sounds, and smells. Dark women in bright yellow and red saris mixed with street vendors shouting out their wares. Tuk tuks bleated and puffed out moist carbon monoxide fumes zipping around bicycle-powered rickshaws. Dogs lolled in the sidewalks, cows ambled through the traffic, while beggars and lepers with watery eyes in ragged loincloths held out their hands and mouthed words I did not understand.

And then I saw the white caps of the majestic Himalayas. I fell in love trekking to Mt. Everest. It wasn’t just the phantasms of the high Himalayas; it was the people who lived up there. Sir Edmund Hillary described the Himalayan villagers who befriended him the strongest and kindest people in the world. He was right. And I had found a second home.

In 1995, my house and family were in Indianapolis, where I lived with my wife Alicia and our two boys. But, mid-life alienation had disrupted the warmth and equilibrium of our home and family life.

I had come to feel trapped by the responsibilities of marriage, children, mortgage, and law practice. The American dream had become Poe’s nightmare of enclosing walls of financial and family pressures.

Work and responsibilities beat and fashion the adult American into a tool of production and consumption. At the systemic level our society and economy value the acquisition of material wealth over all other values. In succumbing to this cultural imperative we are conditioned to believe that our meaning and purpose are determined by job and profession rather than by love, family, and enjoyment of life. To press the point, in our culture when one is introduced the first question is, “What do you do?” Our selves are reduced to a name and a job. It is not that way everywhere.

My high school history teacher, Mr. Slavens, liked to say, “The average American male, dead at thirty, buried at sixty.” I don’t remember who he was quoting, but it haunted me. At forty I was definitely feeling lost, if not dead. I did not want to lose my humanity, but I felt life being sucked out of me as I measured out my days in six-minute billing-units at the law office.

So, Alicia wisely and firmly told me to go traveling, to do what I loved but had been denying myself. Not just a weekend or week-long road trip; she told me I should go take a hike on the other side of the planet. I should go trekking in the Nepal Himalayas.

Fifteen years later, Ganesh Rai, Buddiraj Rai and I sat by a campfire on the Ratnagi Danda, a 10,000 foot high ridge in the eastern Nepal Himalayas. Our trekking group had successfully delivered the equipment to build a little hydroelectric power station for Basa village.

I had gone back to Nepal almost every year during that fifteen year period. In addition to developing the skills and experience of a mountaineer I became involved with various development projects in remote Himalayan villages. The first was a water project in the Dolpo region of western Nepal. In the last few years my efforts focused in the eastern region of Solu, mostly on Basa village. Villagers and climbing friends had formed a foundation to work with Basa to improve its standard of living in ways the local people decided they wanted. A village school with five grades, smokeless stoves for all the homes in the village, a hydroelectric plant, and a water delivery project were the fruits of our efforts. Because of my relationship with the people of Basa, I was called Jeff Dhai, “big brother” to the village.

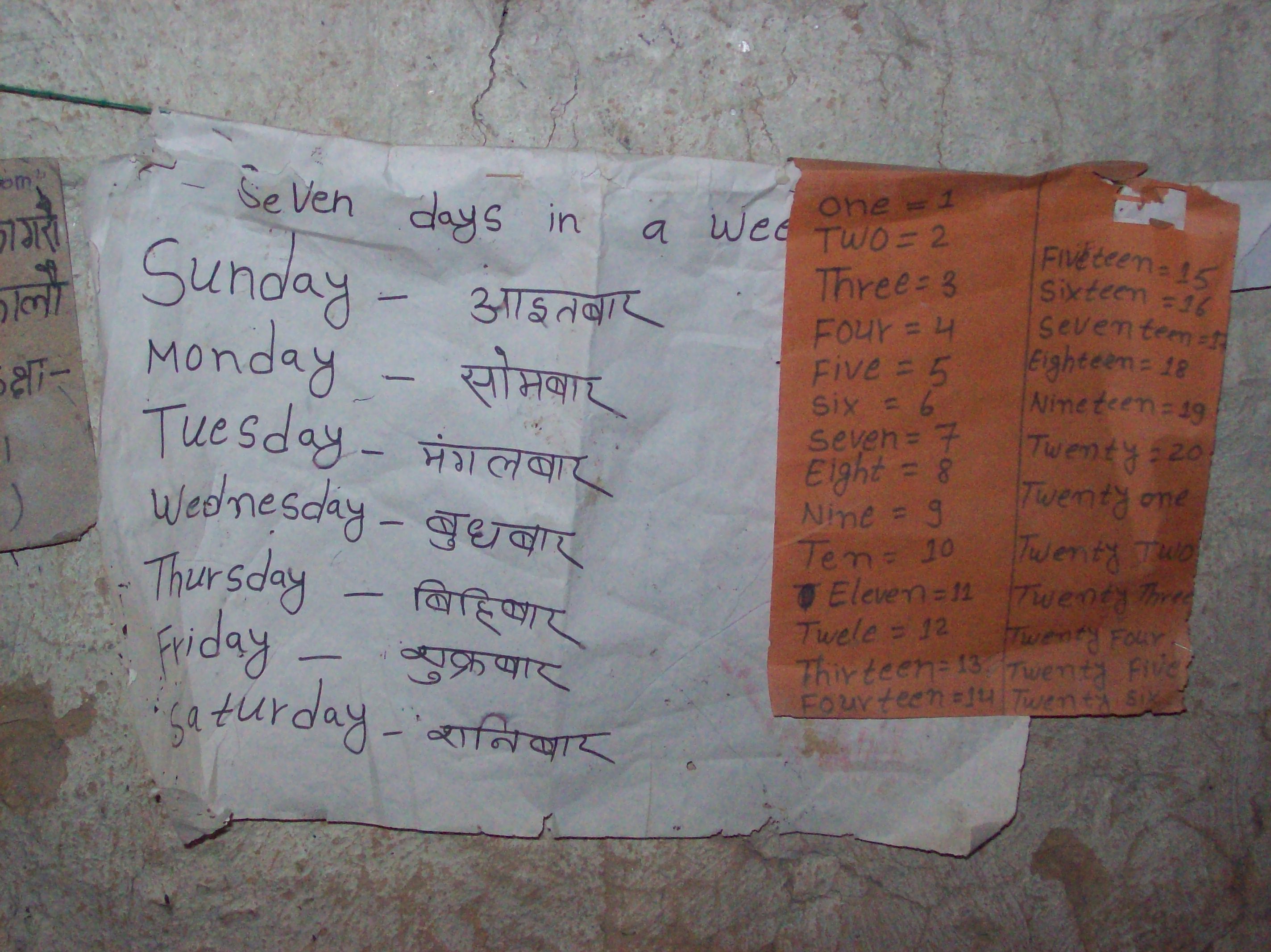

Ganesh and Buddi had agreed to enlighten me about the ancestral legends of the Rai people of Basa. They told me their people “in the old days” had a written language and sacred texts, but the written language and the ancient texts were lost in the mists of time. Their local language was spoken only by the native villagers of their valley. As far as they knew, no other “white man” had been told the stories that had been handed down from generation to generation in Basa.

Our camp was a clearing within a rhododendron forest on the high ridge above the village. The porters and kitchen crew were finishing their simple meals of rice, lentils, and tea. The crew had already cleaned up our communal dining tent. As soon as the guys finished eating they would pile into the dining tent sharing body heat for warmth while they slept.

Before we sat down by the campfire, Ganesh and Buddi had spoken with our senior porter Kumar Rai about my request to be told the old stories of their village. Kumar is a descendent of shamans (called “purkets” in the local Rai dialect) in Basa. He was also the eldest member of our expedition staff. Kumar does not speak English. Kumar assented that the stories of their gods and rituals should be revealed to me. He reminded the younger men of some of the details he wanted me to learn.

Buddi is the son of the caretaker of the Kali Devi shrine outside of Basa. Buddi will succeed his father after the old man’s death. Buddi was the assistant sirdar (guide) for the trekking group to Basa I had organized in November-December 2010. Ganesh was our sirdar (chief guide).

Buddi sat on the other side of the fire from me. Buddi’s voice was low and resonant. He was chanting trance-like in his Rai language. It was a little unsettling, because Buddi is in his mid-twenties and full of life. On the trek he was always smiling and joking while he bounded down the trail on springy legs. Now, he was solemn and serious. His chanting voice on the other side of the crackling fire under the moonlit Himalayan sky created an eerie ambiance.

Ganesh sat between us translating Buddi’s words into English. Ganesh and I have hiked many rugged miles together on trails on Himalayan climbing and trekking expeditions. He was the sirdar for several expeditions we organized to introduce American friends to the alien and wondrous culture of Nepal and the highest mountains on Earth. Our conversations were normally playful, enlivened with jokes and laughter. But Ganesh wasn’t laughing or joking beside the fire pit on the lip of the Ratnagi Danda.

The flames of the campfire flashed and licked at the stack of sticks in the fire pit. Kumar and the guys had placed three stones around the edge of the fire pit as required by Rai taboo. Red sparks wafted up into the great open sky above the Ratnagi Danda. The stars were so bright I could see the Milky Way and the constellations I’d learned as a child. I listened in rapt attention as Buddi chanted and Ganesh told me the ancient stories of the Rai people.

Jeff Rasley is a returning contributor to Synchronized Chaos Magazine, with a prior story about visiting Wounded Knee. He may be reached at jeffrasley@gmail.com

This article warmed my heart and the pictures warmed my soul!