An Experience of Wounded Knee

Goshen Redskins and Peace Times

The population of North American indigenous people was decimated by a 90 percent reduction and the land they controlled was reduced from 100 percent to 2 percent, as a result of the Anglo-European invasion and US conquest. The entire USA has and continues to benefit from the inhumane treatment of the people of the Native Nations.

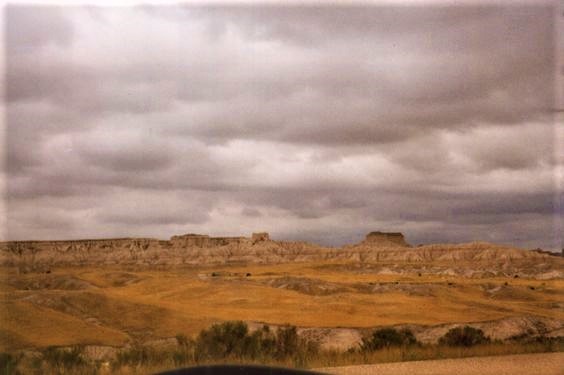

It is shocking and dispiriting to see first hand the land the US government “gave” the tribes of the Sioux Nation for their reservations in the Badlands, after Sitting Bull and Crazy Horse surrendered to end the Black Hills War. The Sioux didn’t even get all of the land, because the government cut out a major chunk of the Badlands to create Badlands National Memorial in 1929. Ten years later the memorial was upgraded to become a national park.

Driving across the bleak, prairie land of the Badlands, you pass forbidding white spires, angry grey cliffs, and squatty buttes. The Sioux people must have felt as desolate as the landscape, when they realized that, of all the lands they had roamed, the most uninhabitable area was where they were to be confined. The oppressive August heat in 2013 emphasized the grim harshness of the sun-baked landscape of the Badlands as I motored along State Road 40.

Evidence of neglect of reservation lands, and the needs of resident Indians, was even revealed in the road conditions to and through the Pine Ridge Reservation. South Dakota’s State Road 40, the road I drove heading southeast from the City of Keystone to the Pine Ridge Reservation, was a well-maintained, paved road. But when it became a Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) road within the reservation, the pavement ended. My vehicle had to endure forty miles of gravel whacking its undercarriage to reach Wounded Knee. Pavement reappeared when I left the reservation.

I stopped at Badlands National Park before driving through Pine Ridge to Wounded Knee. After reviewing the historical and geographical information at the Park Visitors Center, I asked the sole ranger on duty what I would find at the actual site of Wounded Knee. The ranger was tall, lanky, and had the weather-beaten good-looks of Gary Cooper. His laconic reply to my question was, “There’s not much there.” His answer was correct on the surface, but at a deeper, personal level, he was wrong.

On the east side of the dirt road at the site of the massacre were a couple of forlorn-looking booths with beaded belts, necklaces, and other handcrafts for sale. An elderly Indian in a stained white t-shirt with a Fruehauf Truck cap shading his eyes was asleep on a metal folding-chair behind one booth. A couple kids played in the dirt under the other table. On the west side of the road was a curved structure of wood and concrete with a sign indicating it was the American Indian Movement Center.

Inside, the walls were covered with posters and propaganda for AIM. The sparsely furnished interior had a long counter with an aged metal cash register. Piles of t-shirts, books, and handmade trinkets were for sale on top of rickety tables. The “library” consisted of several boxes of cut-out newspaper and magazine articles, a few dusty hardback books, and a scrapbook about the history of AIM.

Behind the building were two small hillocks with graveyards on top of each mound. An elderly Indian wearing a faded cowboy hat, dirty jeans, and stained t-shirt was leaning against the side of the building smoking a hand-rolled cigarette. I asked him if there was a monument to those who were killed at Wounded Knee by the US Cavalry. He looked me up and down without registering any expression. He slowly raised his arm and pointed toward a fenced area beyond a number of grave markers on the closest mound. I thanked him. He made no reply.

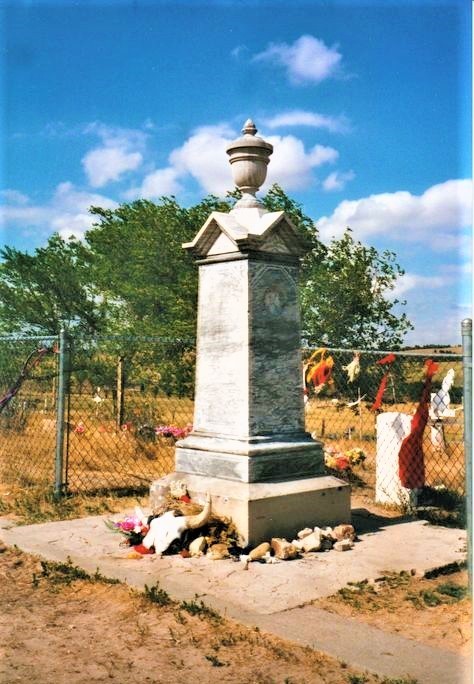

The fenced area for the memorial was about ten feet by six feet. A six-foot high granite monument stood inside the fenced area. Names of victims and a few words about the massacre were incised on the monument.

While we know that at least 200 – and it was probably closer to 300 of the 350 Minneconjou Sioux in Spotted Elk’s band – were killed at Wounded Knee, I counted fewer than 40 names on the monument. I don’t know whether the other names are lost in the mists of history. The skull of a horned steer was placed at the base of the monument. Shards of broken pottery, a few faded flowers, ribbons, and a couple fake gold coins were scattered around the base of the monument.

I placed two stones on top of the weather-beaten skull. I had purchased the rocks for one dollar each from two Oglala Sioux kids at the intersection of two gravel roads within the Pine Ridge Reservation. Their father told me he wanted to “encourage entrepreneurship” in his kids. Beaming with pride, Dad explained how his two boys search for nicely-shaped rocks, polish the best ones they find, and then sell the shiny stones on the roadside to people driving through the reservation.

How brave and pathetic! My heart ached for those kids and their dad.

It seemed like an appropriate symbolic gesture to pay for those two little pieces of the land and then give the polished stones back by leaving them at the memorial to Spotted Elk and the Minneconjou who were killed by the bullets fired by my ancestor, First Lieutenant James DeFrees Mann, and the soldiers of the 7th US Cavalry.

No one else entered the small cemetery during the half hour I spent on the hillock meditatively eyeing other grave markers. I shielded my eyes from the sun and gazed back across the road beyond the AIM Center. It was just over there, on the other side of the road, where Spotted Elk and his band of 350 Minneconjou Sioux had camped under the watchful eyes of Lt. Mann and the cavalrymen of K Troop. Beneath the soil of the earthen mound where I stood are the bones of the men, women, and children, whose bodies were tossed into the mass grave dug in the days following the massacre. The remains of more recently deceased residents of Pine Ridge Reservation share that little plot of raised earth with Spotted Elk and his Minneconjou.

Back inside the AIM Center, I tried to make conversation with a stoic-looking middle-aged woman, who was sitting behind the counter with a few kids. She didn’t give her name, and I didn’t ask. No other visitors entered the building while I was there.

I overcame my hesitation and told her about my ancestor’s participation in the Wounded Knee massacre. She evinced no hostility; just gazed evenly at me through tired brown eyes. She wore a blue work shirt buttoned up the front, jeans, and had long, straight black hair, which almost reached her waist.

She said she didn’t know anything about the cavalrymen involved in the massacre, and didn’t recognize Lt. Mann’s name. My look of surprise registered with her. She looked away, then pursed her lips and said that maybe she remembered reading an old newspaper that mentioned Lieutenant Mann.

A boy, who looked to be about ten years-old, studied me with watchful, curious eyes, when I was perusing the library materials. Later, while I was conversing with the Center’s attendant, the lad listened intently to our conversation. When the conversation wound down, the woman nodded at the boy and told me he was her son. That seemed to be the cue he’d been waiting for, because he launched into an obviously prepared speech requesting a contribution to a fund for his baseball team. He held out a rumpled leaflet for me to read. His limpid, brown eyes shone with excited anticipation. I gave him a ten-dollar bill, tapped the brim of his baseball cap, and wished him and his team good luck. His mother’s lips turned up very slightly at the corners. It was almost a smile; the first and only indication of friendliness I received from his mother. Her son thanked me and shook my hand formally.

Before I left the AIM Center, I bought a t-shirt for twenty dollars with the American Indian Movement logo on the front and back. The logo was the figure of an Indian warrior with two feathers in his hair shaped to look like the two-fingered gesture of victory.

I fantasized time-traveling back to high school and wearing the AIM shirt to a basketball game. Our varsity teams were the Goshen Redskins. The mascot was a little White kid, whose cheeks were streaked with red “war paint”. During my K through 12 years in the Goshen Community Schools, “Little Chief” wore an elaborate buckskin outfit with a feathered-headdress. He led the basketball team onto the court for warm-up drills before the start of each home game. During warm-ups, Little Chief stood at mid-court with his arms crossed like a dignified Indian chief. The little White boys chosen to be Little Chief were always about the same age as this boy, who looked at me with wide-eyed curiosity when I entered the AIM Center and shook my hand before I left.

My junior year in in high school, a young woman fresh out of college was hired as our journalism teacher. Ms. Thomas allowed students to change the name of the school paper from The Tomahawk to The Goshen Peace Times. Instead of bland, rah-rah school-spirit articles, The Peace Times published anti-Vietnam War articles and reviews of rock music. It printed an editorial suggesting that the team name should be changed out of respect for Native Americans. The editorial was met with almost universal hostility. It was condemned by townspeople, faculty members, school administrators, and many students. No Indians had complained about our mascot being offensive, nor had any tribes demanded that the school change the name. It was outrageous blasphemy against our customs and traditions even to suggest such a thing!

Ms. Thomas was rebuked for allowing her student-journalists too much freedom of expression. The high school administration shut down The Peace Times after that outrageous editorial. The young, idealistic journalism teacher left town at the end of the school year. But a couple decades later, in 2016, the Goshen Community Schools Board decreed that the team name would be changed from Redskins to Redhawks.

The Goshen News

I left the AIM Center and drove into the “town” of Wounded Knee, which was just around a bend on the unpaved BIA Road 28. A rusted metal chair stood in the middle of the dirt road running down the center of town. Resting on the rusty chair was a hand-painted sign on poster board. It read, Drive Slow Stop Killing Our Children.

Wounded Knee had the depressed ramshackle look of other settlements I’d driven through on reservations in South Dakota. But it was the worst. It was and is a squalid, poverty-stricken settlement with dilapidated houses and rusting mobile homes. When I was there, trash littered the street. An old woman walked across the dusty road in front of my car. She looked at me through the car’s window without registering any emotion. Her eyes were dull and her movements listless.

The Census Bureau’s information on the town of Wounded Knee for 2018 reports a population of 456 with a median household income of $7,292, which has fallen, instead of rising, since I was there in 2013. Between 2017 and 2018, the population of Wounded Knee declined from 521 to 456. According to the Census Bureau, the poverty rate is 95.2%, and only eleven residents are employed. The median household income for the State of South Dakota in 2019 was $58,275, about 8.5 times higher than the median family income in Wounded Knee.

The median age reported for Wounded Knee is 21.6. In South Dakota it is over 40. Several Trip Advisor descriptions of tourist experiences at Wounded Knee and the Pine Ridge Reservation include complaints of being accosted by young men demanding money or trying to scam tourists. Not that I approve of scamming tourists, but what exactly are young people supposed to do in a community with a poverty rate of 95.2 percent?

If America is going to continue to claim it is a moral leader, the “city on a hill” and beacon to the rest of the world, we have to finally and fully face up to our genocidal history and national sin.

Excerpted from America’s Existential Crisis: Our Inherited Obligation to Native Nations by Jeff Rasley, Midsummer Books 2021, exclusively available on Amazon.