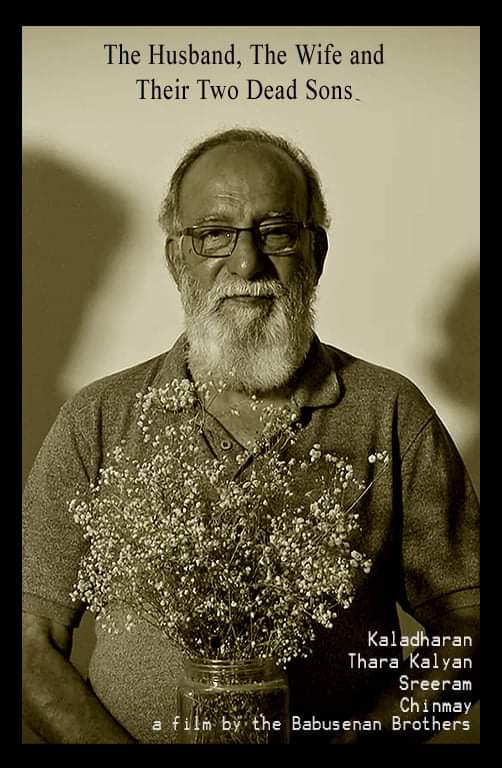

The Husband, The Wife, and Their Two Dead Sons Review

Satish and Santosh Babusenans’ Winter of Discontent

The world of Santosh and Satish Babusenans’ cinema lures me in. Their lush cinematography, toned-down visuals, and deep philosophical undertones make their films a train of thought for the soul. Their newest film, “The Husband, The Wife, and Their Two Dead Sons” uses scenery resembling Korean and Japanese cinema masters of manipulating time. Asian cinema is a breed of its own, leaving spaces for breathing between shots, and allowing characters to grow through a scripted dialogue that feels rich and compressed. The Babusenans always create a sense of presence in their films. They are not concerned with the past or the future but with what is in front of the camera.

Time is an integral part of the Babusenan brothers’ cinema. Events stretch and extend, shots are long, and cameras are left rolling and absorbing whatever events are happening onscreen.

Kaladharan Sika is no doubt the Babusenan Brothers’ muse and inspiration. These two use him for the essence of what their cinema wants to say; wisdom, philosophy, the passage of time, sickness, and death.

Ever since the first film I saw by Satish and Santosh Babusenan, I’ve known them to be explorers of major themes and complex topics through the lives of simple people. Through a dissection of the day-to-day Indians going on with their lives, intertwining and mingling through various explorations of sexuality, existentialism, mortality, and morbidity.

Death in the Babusenan world is neither created nor destroyed. It is not a challenge to be conquered nor a feast to be celebrated, but like many Eastern Asian philosophies and religions, it is present as a parallel to life. They coexist in harmony and lead others through and through. Talking to dead people, accepting death, or questioning it does not seem like a part of a gigantic Western epic but more of a natural part of the course of life. That is what Narendran does with his dead sons. A conversation is still a conversation. The fact that half of it is in the land of the living and the other is not part of this world doesn’t change a thing. There’s no eeriness or creepiness in the mood. Death is just there and so are life, sexuality, birth, and mythology.

In this mystical tale of spirituality and modality, Narendran is a man who has come to terms with Death. Like Bergman’s “The Seventh Seal”, Narendran plays board games with Death, and has existentialist conversations with the Grim Reaper, as represented by his two late sons. He seems to have solved the ultimate dilemma of life. He made peace with the ones who left and the aftereffect of loss and grief. But even as Narendran’s world harmoniously unravels the equation of death, his morality, philosophy of life, dreams, and aspirations are challenged as he faces the epitome of challenges, a death beyond his capacity for acceptance, a void more prominent than his burden to bear.

Satish and Santosh Babusenan dissect Indian society, touching on heavier stuff such as familial ties, financial struggles, and patriarchy. Absent fathers who traveled to secure a better life for their children who -in turn- were not appreciative or celebratory of their parents’ decisions. Mostly the Babusenan brothers rely on familiar worlds, familiar territories, and faces. Their heroes and muses are usually the same, their stories doused in the local flair.

The Babusenan brothers do not fear voicing their passion or dissatisfaction with the world. Their characters are highly opinionated, expressive, and thoughtful. Their films reflect deep thinking and a technique that relies on realism and minimalism. Conversations in “The Husband, The Wife, and Their Two Dead Sons” are crucial to the plot dynamics and they are left unscathed, unedited. Richard Linklater script types where people’s dynamics are at the narrative’s core while heavier Bergman philosophical questions immersed in French realism are in control of the stylistic aspects of the films.

Ever since their first film, “The Painted House,” the Babusenans have been asking questions they seek answers to along with the viewers. But as their filmography progressed they stopped inquiring and became more introspective, more intrinsic in their quest to decipher the big mystery of the world. Their fiery spirit might not have died, nor has their fights with artistic oppression, but their nature has become more docile and forgiving, their technique more confident.

A different color palette dominates throughout the film, from shades of dark blues to orange hues, greens of the outdoors, and open spaces to dark shadows as Narendran faces his deepest fears and existential wonder. Forced into a corner when his wife’s death looms on the horizon, Narendran confronts his faith and the so-called harmony he has made with Death.

“The Husband, The Wife, and Their Two Dead Sons” is a movie for all the senses. This movie demands feelings and empathy. It projects its themes through a lens of humanity and understanding. Characters are going through crises of faith, certainty, and disillusionment, replicating their feelings through a series of events and sequences well crafted by the Babusenan brothers.

In a particular scene, an unseen character is quoted as asking one of the dead sons, “Do all poets love to be sad?” This question got me thinking about what defines the Babusenan brothers’ films. Is it melancholy? The eerie inevitable feeling of finite possibilities and endings to a life rattled with questions and accusations. Is it the monotony of rotating time or the familiarity of actors’ faces interloping from one film to the other? But I realized that it was all of the above. Against all odds, fighting a systemized global opposition to alternative art and artists, the Babusenan brothers carved their names as veteran filmmakers and authentic creatives. From their hearts and minds came a series of films that map out a world so intricate in its simplicity. For viewers from different parts of the world, the Babusenan brothers will stand out as proud artists who have refused to mold into more approachable moviemakers and auteurs, and for that alone, still they rise!