Write a note on historical sense in the light of T.S. Eliot’s “Tradition and the Individual Talent”.

Or

Summarize Eliot’s attack on the romantic theory of literature as revealed in his Tradition and Individual Talent.

Or

In many ways, Eliot has proved himself to be the most important critic of our century. Elucidate.

Or

Critically examine T. S. Eliot’s Coleridgean theory of imagination.

Or

Write a brief note on I. A. Richards’ disagreement with Aristotle’s belief that the command of metaphor: “cannot be imparted to another; it is a mark of genius, for to make good metaphors implies an eye for resemblances.”

Or

Evaluate I. A. Richards’ contribution to literary theory.

Or

Briefly explain I. A. Richards’ application of impulses in literature.

Or

Explain the main difficulties of sensitive criticism as pointed out by I. A. Richards.

Or

Drawing on the work of at least three critics prescribed for this course, discuss the principal changes in theoretical orientation in twentieth century literary criticism.

Or

For Coleridge fancy is the drapery attiring the poetic genius while imagination is its soul, which forms all into one graceful and harmonious whole. Coleridgean theory of imagination is distinguished as literary aesthetics: literary theory abstracted as impressionistic criticism. Sensations and impressions from the external world coalesce and merge with the faculties of the soul—-imagination, perception, intellect and emotion to undergo the creative process of artistic creation through formerly selection and ordering, and latterly being reshaped and remodeled as “esemplastic phenomenon” to endow entirely new finished product in the form of a chemical compound from the elements of mechanical mixture.

In literary aesthetics of Biographia Literaria, Coleridgean rhetoric of the Wordsworthian poetic theory and poetic diction stipulates the faculties of the imagination as either primary or secondary with greater depth, penetration and philosophical subtlety. Primary imagination is universalized as unconscious and involuntary perception of the sensations and impressions of the external world with the internal mind as the living power, and prime agent of all human perception as a repetition in the finite mind of the eternal act of creation in the infinite I am. Secondary imagination is more active, more conscious and more voluntary, and a result of volition than the primary imagination.

With this distinct and peculiar imagination the poet’s the soul of the faculty of imagination possess magical synthetic power in order to synthesize or fuse the various faculties of the soul—-imagination, perception, intellect and emotion ie, the internal with the external, the subjective with the objective, the spiritual with the physical and material. By the conscious effort and volition of the will and intellect, the secondary imagination selects and orders the raw materials and reshapes and remodels it into objects of beauty. It is esemplastic ie. A shaping and modifying power by which its plastic stress—reshapes objects of the external world and steeps them with glory and dream that was never on sea and land. The secondary imagination is a reechoing of the former [primary imagination], coexisting with the conscious will, yet still as identical with primary in the kind of its agency, and differing only in degree and the mode of its operation. It dissolves, diffuses, dissipates, in order to recreate, or where this process is rendered impossible, yet still, at all events, it struggles to idealize and to unify. It is essentially vital, even as all object[as objects] are essentially dead and fixed. In terms of fixities and definites, fancy dwells as a memory emancipated from the order to time and space.

Write a note on historical sense in the light of T.S. Eliot’s “Tradition and the Individual Talent”.

Or

Summarize Eliot’s attack on the romantic theory of literature as revealed in his Tradition and Individual Talent.

Or

In many ways, Eliot has proved himself to be the most important critic of our century. Elucidate.

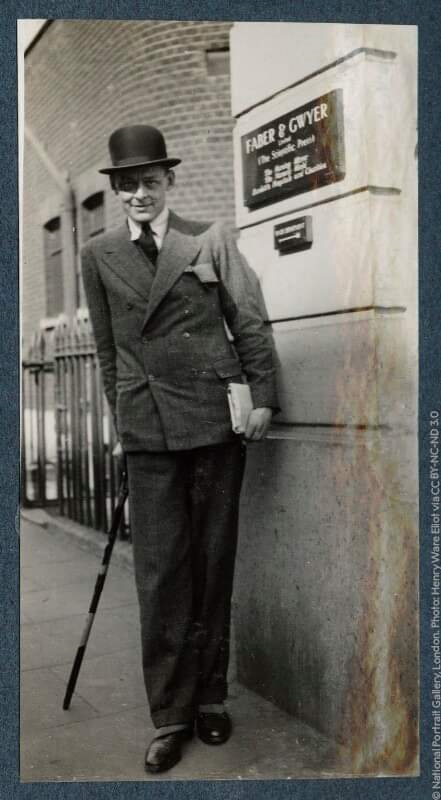

Cleanth Brook’s rewriting of literary history in Modern Poetry and the Tradition traces back to revisit “deep, hidden connections” of metaphysical aesthetic culture essayed by T. S. Eliot. Eliot and Brook’s unity and community have theological implications that signified God-terms implied in the semantic lexis of their works: modernist poetics and new critical practice. Eliot’s advocacy as a spokesman in the preservation of educational communities and European civilization as a whole within the cloister against anarchy, mutability, decadence, futility, contamination and dehumanization from the deluge of barbarism or savagery: rehabilitation of a system of beliefs known but now discredited. “Literature should be unconsciously, rather than deliberately and defiantly Christian—-ethical and theological standpoint of literary criticism finds fullest expression in the New Criticism of Cleanth Brooks; paradox and tensions resolve themselves into pure orthodoxy. The end of civilization was the temptation of being marketable to scientism and secularism: “I am using art in the sense of a description of an experience which is concrete where that of science is abstract, many sided where that of science is necessarily one sided, and which involves the whole personality where science only involves one part, the intellect. These are qualities which are essential to a worship, and a religion without worship is an anomaly.

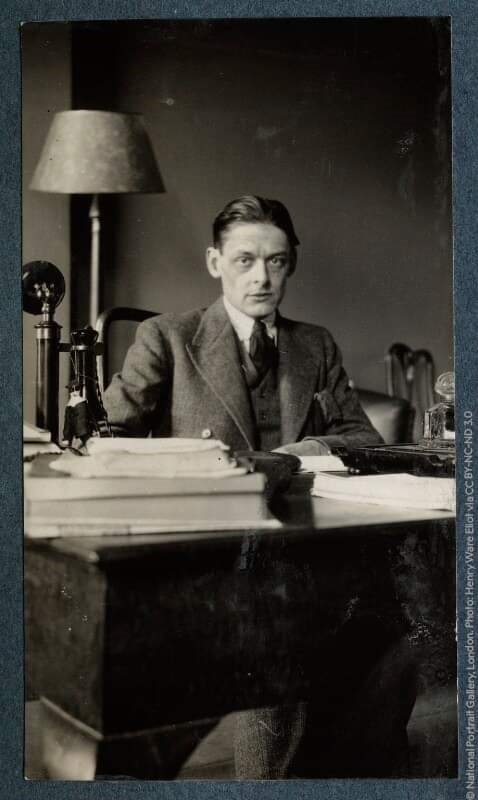

T. S. Eliot emphasizes the immortalization of impressionistic works of art brimming by the period of full maturity within the coalescence of the living past with the timeless and temporal together. Essayist distinguishes retelling and revisiting, rewriting and rethinking through distinction between the present and the past is that the conscious present is an awareness of the past in a way and to an extent in which the past’s awareness of itself cannot show. Continual self-sacrifice and continual self-extinction of personality ought to be the verdict in modernist literary criticism. The mind is a filament of platinum—the catalyst that is inert, neutral and unchanged; passions are raw materials to be transmuted and the mind becomes the receptacle for a combination of feelings, images, phrases, emotions as instanced in the Voyage of Ulysses, the murder of Agamemnon and the agony of Othello. T. S. Eliot’s disapproval of Wordsworthian poetic formula “emotions recollected in tranquility”; since there is neither emotion nor tranquility, nor without distortion of meaning turning loose of emotion; not the expression of personality but that of escape from personality.

Afterall the formulated phraseology of the ceremonial celebration in Tradition and Individual Talent is of impersonalization and multiplicity of narrative perspectives “only those who have personality and emotions know what it means to want to escape from these things” as in “We are glad to be scattered. We did little good to each other.” Eliot’s silence of the relation of present in the future text is revelatory of the anxiety over his own place in the critical tradition—-a lack which await to be supplemented by appearance of future texts through comparison and contrast to a greater or a lesser degree.

T. S. Eliot emphasized the aesthetic and appreciative arguments or statements revealed in the personality of the poet implied through the characters actions and behaviour in the form of a “projection of personal qualities”. Eliot’s theory of depersonalization or impersonalization is a spontaneous artistic process: theory of indirect self-expression. The famous catalyst “filament of platinum” emblematizes the poetic mind detached, the materials of the poem—-the “feelings” [sulfur dioxide] related to images and “emotions” [oxygen] related to situations are internal; the poem is created by a process of “fusion”, which occurs under intense pressure. The fusion depends upon the following characteristics: [1] the emotion of the “man who suffers” [2] the transforming power of the creative process [3] the fortunate critical moment —- the “concentration” that produces the right combination of elements. Unlike Longinian tradition of “inspired passion” the “intensity of the imaginative pressure” is of paramount value in the artistic process of fusion to produce the “newly formed” art work [sulfurous acid]. E.M.W. Tillard suggest that T. S. Eliot’s theory of depersonalization/ impersonalization is in fact a disguise of the self- expression: “The more the poet experiences this abandonment, the more likely the reader to hail the poet’s characteristic, unmistakable self.”

Eliot’s concept of the poetic mind as the filament of platinum catalyst has similarities to the Romantic analogue of the Lamp, discussed by Abrams in Mirror and the Lamp. Both Eliot and the Romantics emphasize the qualities of the external [images and situations] as a reflection of the internal [emotions and personal characteristics]—that is the personal expression of the poet, as opposed to the representation of the world in which he lives. The catalyst, however, is not projective, the mind of the poet remains outside of the “newly formed” art. Objective poetry and objective equivalents to the characters emotions, motivated by the situations and images which correlate to suffice to those emotions, must be closely if not necessarily the same and this empirical philosophy is evidenced in objective poetry “everywhere the feelings of the author penetrating even in the innermost depths of the poet’s most intimate individuality —-gleams through.

It is a sense of the timelessness as well as that of the temporality that makes a writer traditional; tradition cannot be inherited but worked through the “historical sense” based on “his own generation in his bones” and “the whole of the literature of Europe from Homer and within it the whole of the literature of his own country”. Eliot disfavours a subjectivist or individualistic ground of poetic activity and rather privileges the relational and collectivist groundwork of creative activity; abnegating Wordsworthian perspective “emotion recollected in tranquility” but appreciating” a continual self surrender” in the vein of “a continual self-sacrifice” and “a continual self-extinction of personality”. Eliotic memorabilia associative theory of depersonalization traces the analogy between the poetic mind and the “filiated” platinum shred that makes possible the creation of new chemical compounds through artistic or creative process of fusion. “The life of our heritage of literature is depended upon the sustaining continuance of literature”, a suggestion positing that there is an organic relation between the poetry past and the present. Hence, the youthful passion of the living young poet in recollection for the dead should be preserved in commemoration as “bearer of tradition” alluding to the beneath latent meaning that “contemporary poetry is deficient in tradition”. “The Transhistorical English mind” relates to the doctrine philosophizing “the mind of Europe as to be in the light of eternity contemporaneous”.

Further Reading

John N. Dunvall’s Eliot’s Modernism and Brook’s New Criticism: Poetic and Religious Thinking, The Mississippi Quarterly, Winter 1992—–93, Volume 46, No. 1, pp. 23-37 [Memphis State University]

T.S. Eliot’s Tradition and the Individual Talent, Perspectiva, 1982, Volume 19, pp. 36-42, The MIT on behalf of Perspecriva

John Steven Child’s [Sam Houston State University] Eliot, Tradition and Textuality, Texas Studies in Literature and Language, Fall 1985, Volume 27, No. 3, pp. 311-323, University of Texas Press.

Allen Austin’s [Indiana University] T. S. Eliot’s Theory of Personal Expression, PMLA, June 1966, Volume 81, No. 3, pp. 303-307, Modern Language Association

Peter White’s “Tradition and the Individual Talent Revisited, The Review of English Studies, June 2007, New Series, Volume 58, No. 235, pp. 364-392, Oxford University Press

Write a brief note on I. A. Richards’ disagreement with Aristotle’s belief that the command of metaphor: “cannot be imparted to another; it is a mark of genius, for to make good metaphors implies an eye for resemblances.”

Or

Evaluate I. A. Richards’ contribution to literary theory.

Or

Briefly explain I. A. Richards’ application of impulses in literature.

Or

Explain the main difficulties of sensitive criticism as pointed out by I. A. Richards.

I. A. Richards is ubiquitiously a major presence and influence into the history of literary criticism and theory as well as composition and rhetoric. I. A. Richards was so deeply influenced by Coleridge to study I. A. Richards is to see Coleridge through the lens and filter of a scholar-teacher relation who believed profoundly in the utopian potential of science, thus paradoxically embodying the romantic belief that all knowledge is personal and subjective as well as the modernist faith in the objective empirical science. We are reminded of the following problems in reading poetry in view of classical literary theory: making the plain sense, difficulty with sensuous apprehensions, difficulty with imageries, mnemonic irrelevancies, stock response, sentimentality, inhibition, doctrinal adhesion, technical presupposition, general critical preconception. From Coleridgean theory of imagination —-the hegemony of both composition and “literature of fact” posit in the historical sense of composition has been on the fringes or the ghetto of the humanities and this alludes to biography, critical interpretations, autobiography, essays, non fiction, memoirs, and histories as peripheral in literary studies. Richards does not explain how the mind bridges the gap supplied by the print and the meaning derived therefrom. The mind organizes the perception and the object now becomes a projection of our sensibility and in this sense is knowable. Richards claims that the wealth of scholarships including dictionaries, concordances, critical commentaries and biographies as scholarly aids that “does not lift our heart as it should do”. Richards indoctrinates that contiguity is reproductive leading to stultification and conformity, while similarity “extends and develops” leading to resourcefulness and constructiveness.

The enlargement of the mind and the widening sphere of human sensibility is brought about through poetry. I. A. Richards claims that imaginal actions and incipient actions … are more important than overt action. Since attitudes are these actions embodied by resolutions, interanimations and the balancing of impulses…that all the most valuable effects of poetry must be described.” “It is not the intensity of the conscious experience, its thrill, its pleasure or its poignancy which gives it value but the organization of impulses for freedom and fullness of life.” Meanings are produced organically from our adaptations of the past experiences to the needs of present life… “as representations does not encroach upon our present; it inhibits as the very conditions of its experiences.” Richard Forster argues, “changes in language mean changes in the colouration of the thought which they embody—-changes, that is, in “sensibility”. I. A. Richards theorizes the pseudo statement in which intellectual references is a mere-condition for the expression of the emotive impulses. “The facts of mind” are in opposition to doctrines and formulations, parallel closely the emotive impulses which are opposed to references. Richards’s theory of Creative Imagination and by extension of the nature of poetry—-“projective-realist synthesis”—–a reconciliation of the “realist doctrine—-the mind perceives the objective reality in nature——with the projective doctrine—-the mind perceives only a projection of its “feelings”, “aspirations” and “apprehensions”. Richards synthesis of realist and projective doctrines is the effect of synchronization with harmony of Richards’s own materialism and Coleridge’s idealism—-emotive assertion incapable of conflicting.

I. A. Richards indoctrinates that the “Good Sense” is “representative and reward of our past conscious reasonings, insights and conclusions.” Poetry should not merely live moral adhesion towards religion, ideology or tradition rather we should consider the aftereffects the capacity to organize and govern life as the organic whole of the being, the perfection of the self and the judgement of aesthetics ;ie, the self-completion of the humanity within individuality. / “And all things may live from pole to pole/ Their life the eddying of their living soul”…Richards language laboratory encapsulated in the workshop criticism that adopts technological advancement in the new modernism cover such instruments such as radio, cassettes, films, slides, video and computers in the vein of much Shelleyan Prometheus Unbound: “And arts, though unimagined, yet to be”, which he would not return to the old routine in Frost’s “knowing how way leads on to way”. History and tradition are the seamarks and lighthouses —–sometimes wise counsellors, but like Dante or Virgil we turn them in a final moment of choice, we discover we are alone. Richards new workshop criticism and formalist tradition might be implicated as Janus faced —in one direction the linguistic object and the way of looking toward the reader’s imaginative response, judgement, sincerity and modification in the self, and the other in the direction —–the way of looking toward the imagination and normality of the artist, the aesthetic value of society and the state of affairs of the culture. “Its nature is to be not a part, nor yet a copy of the real world [as we commonly understand the phrase], but a world in itself independent, complete, autonomous.”

Further Reading

W. Ross Winterowd’s I. A. Richards’s Literary Theory and Romantic Composition, Rhetoric Review, Autumn 1992, Volume 11, No 11, No. 1, pp. 59-78, Taylor and Francis Ltd.

Jan Cohn’s [Carnegie Melon University] The Theory of Poetic Value in I. A. Richards’s “Principles of Literary Criticism” and Shelley’s “A Defense of Poetry”, Keats-Shelley Journal 1972/1973, Volume 2, No. 21/22, pp. 95-111

Louis Mackey’s Theory and Practice in the Rhetoric of I. A. Richards, Rhetoric Quarterly, Spring 1997, Volume. 27, No. 2, pp. 51-68, Taylor and Francis Ltd, University of Texas at Austin.

G. A. Rudolph’s The Aesthetic Field of I. A. Richards, The Journal of Arts Criticism, March 1956, Volume 14, No. 3, pp. 348-358, Wiley on behalf of The American Society for Aesthetics.

Gerald E. Graff’s The Later Richards and the New Arts Criticism, Summer 1967, pp. 229-242, Wayne State University.

Examine New Criticism in the context of Cleanth Brooks’s Canonization: The Language of Paradox and the hearsay of paraphrase.

The reading of Brooksean “The Canonization” espouses a sense within commonplace American New Criticism in which paradox is the language appropriate and inevitable to poetry. Cleanth Brooks recurrently deplores the deadening effect of cliches, stereotypes, odds and ends of the rhetorical junk on the mind. Brooks states that the function of literature is to keep the language alive —–to keep the blood circulating the tissues of the body politic. Cleanth Brooks examines Wordsworth’s Intimations Ode not merely as a historical document of spiritual autobiography, but as an independent poetic structure, even to the point of forfeiting the light which his letters, his notes and his other poems throw on difficult points. The Well Wrought-Urnism alludes to a rigid, static shape contrasting fluid and dynamic nature inherent in poetic structure catalyzing the poet and the reader. John Donne’s “half-acre tomb” metaphorical paradox is analogous to William Wordsworth’s ante-chapel, cell, oratories, sepulchral recesses and edifices of gothic cathedral. The core meaning and valuation of a literary work; interpretation and evaluation shouldn’t be focused on the readers’ psychology and the history of taste; literary biography and literary history are peripheral or secondhand [hearsay] evidence presented by the text itself. Close reading becomes the hallmark feature of the spectacle of New Criticism since platonic concept of readership transcends flesh and blood intoned around critics assertion of quality and value.

Cleanth Brooks indoctrination of the organic dramatic conception of poetry is implied in the reconciliation of discordant feelings, attitudes and impulses through unification and harmonization of tensions, conflicts, incongruities, ironies, subtleties and paradoxes, resulting with coherence, sensitivity, depth, richness and tough-mindedness of drama and fiction. Cleanth Brooks’s ceremoniously and sanctimonious receptivity of the well-wrought urn consecrates the imagined funerary urn for commemoration and memorialization in loves’ martyrdom and sainthood: “The poem itself is the well-wrought urn which can hold the lovers’ ashes and which will not suffer in comparison with the princes ‘half-acre tomb’.” The inscriptional qualities that Brooks familiarizes of the New Criticism that poems are integrated and isolated texts which survive their authors, addresses, contexts as acclaimed in the lapidariness that entails epigraphic and epitaphic rather than being Orphic dialogue of the humanist and antiquarian interests in inscriptions. The metaphorical object is the memorial urn that proves to be an analogue for the ordered structure of the poem; a figure of remembrance, reflection and /or recollection. Brooks’ contribution is to endorse the form as the uniquely poetic achievement of versification in fashioning a memorabilia souvenir for the deviser through its enduring well-wrought urn form alone.

Further Reading

Cleanth Brooks’ New Criticism, Fall 1979, Volume. 87, No. 4, pp. 592-607.

Herbert J. Muller and Cleanth Brooks’ The Relative and the Absolute: An Exchange of Views, The Sewanee Review, Summer 1949, Volume. 57, No. 3, pp. 357-377.

William N. West’s Less Well-Wrought Urns: Henry Vaughan and the Decay of the Poetic Monument, ELH, Spring 2008, Volume. 75, No. 1, pp. 197-217, North Western University

Discuss the theory of modernism with references to and illustrations from T. S. Eliot and Virginia Woolf.

“Moments of being” marks the hallmark adage of referencing past lives in contextualizing the present(ness) in modernism epoch by Virginia Woolf—the pioneer of stream of consciousness movement. Both Eliot and Woolf have strongholds of advocacy as curators of tradition, culture, history and time, mimesis, repetition, mirroring the present back to itself through a hybridized prism of form that acknowledges the past through revisions and refinements, dismantlement and preservation of literary and cultural artifacts in the affinity of shifting cultures, traditions, histories, topographies, desires and textualities. T.S. Eliot’s languishing lamentable mourning severance in time from experiencing the past with direct apprehensions of what the past craves, but that it involves both the past and the present times as simultaneous and interdependent, that repetitions denote change, and that our existence in time is a constant oscillating reflux between obscurity [oblivion] and memorialization [reminiscence], being conscious of the uniqueness of the present in correlating the awareness from past(ness).

Eliot misunderstood tradition as [a]tradition in a way that operates as a trump for temporality, a foil for time and offering itself to the present by way of an encounter with the eros of the past. “The past should be altered by the present as much as the present should be directed by the past. Elisa K Sparks states that in “Tradition and the Individual Talent” Eliot conveys “absolutist aura of authority” in a system that constructs “imaged in figures that stress hierarchy and rigidity”. Eliot’s analogy of both literary history and cultural memory is in fact, radically dialogical; there is no order of absolutes, but rather an everchanging arrangement of “combinations”: past should be altered by the present as much as the present is directed by the past. Sandra Gilbert and Susan Gubar have misunderstood the theory of impersonality or depersonality implicated by the insistence of: “the Eliotian theory [propounded in Tradition and the Individual Talent] that poetry involves ”an escape from emotion” and “an escape from personality” constructs an implicitly male aesthetic of hard, abstract, learned verse as opposed to the aesthetic of soft, effusive, personal verse written by women and Romantics. Thus in Eliot’s critical writing women are implicitly devalued and the Romantics are in some sense feminized.”

Further Reading

Modernism, Memory and Desire T. S. Eliot and Virginia Woolf, T. S. Eliot: Writing Time and Blasting Memory

Examine in detail of Hume’s ‘Of the Standard of Taste’.

Hume’s ‘Of the Standard of Taste’ theory embodies the judgement of ideal critics in the light of prima facie worth or value of the masterpiece, canon and masterwork’s intrinsically worthy or valuable experiential affording potentiality or capacity that transcends temporal and cultural barriers to the test of time. These viewpoints of critics verdict might differ because of humour, temperament, cultural outlook, sensibilities, beliefs, customs, practices, traditions and institutions. These rules of art, rules of composition and laws of criticism encapsulated as the general observations tend to the ‘true standards of taste and beauty’ irrespective of countries, ages and environments.; these ideal critics verdict ought to delicacy of taste, are practiced, have made comparisons, are unprejudiced and possesses strong will.

Humean aesthetics “Of The Standard of taste’ jargons the prospect of the perennial question of objectivity of the judgment of taste as exemplified in the paradox between common sense and empiricism. Beauty is literally in the eye of the beholder and the faculty of perception in the mind of connoisseurs and critics; beauty is a feeling or sentiment and not something in the fabric of the artwork. Perfection of the serenity of mind, recollection of thought and attention to the object are prerequisites of the delicacy of tastes and of passion; influencers of the triggering stimulus response behind approbation and opprobrium of the diversified artworks and canon of literature. Pleasure and pain are the core essence of beauty and deformity; therefore painful situations would be perceived as pugnacious and deformed; while qualities evocative of serenity, cheer, calm and so on are associated with situations which are pleasurable and hence are perceived as beautiful. Taste is the metaphor epitomizing all the virtues of human nature through lofty and universal thought and imagination, profound and exquisite feelings—-whether pathetic or sublime. David Hume’s “Of The Standard of Taste” is the foreshadowing of personal and historical fallacies in the Arnoldian poetic tradition. “Mirth or passion, sentiment or reflection, whichever of these most predominates in our temper, it gives us a peculiar sympathy with the writer who resembles us.”

Further Reading

Jerrold Levinson’s Hume’s Standard of Taste: The Real Problem, The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism, Summer 2002, Volume. 60, No. 3, pp. 227-238, Wiley on behalf of The American Society for Aesthetics

James Shelley’s Hume’s Double Standard of Taste, The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism, Autumn 1994, Volume. 52, No. 4, pp. 437-445, Wiley on behalf of The American Society for Aesthetics

Noel Caroll’s Standard of Taste, The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism, Volume. 3, No. 2, pp. 181-194, Wiley on behalf of The American Society for Aesthetics

Carolyn W. Korsmeyer’s Hume and the Foundations of Taste, The Journal of Aesthetics and art Criticism, Winter 1976, Volume. 35, No. 2, pp. 201-215, Wiley on behalf of The American Society for Aesthetics

Ralph Cohen’s [University of California Los Angeles] David Hume’s Experimental Method and the Theory of Taste, ELH, December 1958, Volume 25, No. 4, pp. 270-289

Examine Edmund Burke’s philosophy of the Sublime and the Beautiful in detail.

Elegantly rhetorical and philosophically investigator, Edmund Burke’s A Philosophical Enquiry Into The Origins of Our Ideas of The Sublime and Beautiful [1756], exemplifies the theatrical state polarization effect of a sublime associated with a masculine terror and a beautiful linked to a feminized erotic hedonism is replaced by the realignment of beauty with the feminized chivalric virtues of honour and reverence. Burke’s observation of Marie Antoinette in the Reflections on the Revolutions in France [1790] characterizes feminine qualities with beauty in terms of softness, smoothness, subtle variations, mild colours, roundedness, fragility, delicacy, weakness and even counterfeit weakness. The impetus of this argument envisages delicacy and weakness with the passions that arouse love and desire. Frances Ferguson notes that “recent discussion of the sublime, remarkably, all but delete the beautiful and present the sublime as functioning in supreme isolation from its companion and counterpoise, the beautiful.” Epicurean strains and hedonistic frivolities of the female ought ot be languorous allusiveness to despair, melancholy, dejection and self-murdering in the light of the woman’s body taken to the spectator’s or lover’s amorous gaze; “that quality or those qualities in bodies which cause love, or some passion similar to it,” unfolding that erotic fictions are transposed into facts ; readers are intrigued by philosophical truth rather than succumbing to temptations of romance and erotic enchantment.

Shaftesbury’s argument to Longinus insistence that, “a well timed stroke of sublimity scatters everything before it like a thunderbolt, and in a flash reveals the full power of the speaker” […] Burke’s enquiry exposes the harsh landscape of sublimity as opposed to the realm of beauty—a lush domain of birds, small animals, and variegated flowers —beauty is feminine weakness and delicacy is accompanied by the contention that “these virtues which cause admiration […] are of the sublime kind” and “produces terror rather than love: fortitude, justice, wisdom and the like”. These masculine like virtues do not evoke compassion, kindness, liberality and tender-heartedness—which “engages our hearts” and “impresses us with sense of loveliness.” On the contrary, sublime objects remain impervious to the human agency and efforts of conquering, domesticating and exploiting the natural environment. Take for instance, “How fearfully and wonderfully am I made!”—David’s exclamatory sentence is of sublime significance in interiorizing the act of making but not that of the self-exaltation in the product; we are not so much empowered by sublime contemplation of the divine; we are overwhelmed by the superior agency of the sovereign. As we encounter the vast natural phenomena we are privileged with such “occasions as the removal of pain […] found the temper of our minds […] in a state of much sobriety […] impressed with a sense of awe […] a sort of tranquility shadowed with horror.”

By sublimity we shrink in the minuteness of our very nature, in a manner, as if we are annihilated by the supremacy and sovereignty of the majestic force. The sublime enlarges or diminishes the existence of human beings; heightening the state of being through affirming identity or overpowering to dominate the self. “The passions caused by the large and sublime in nature, when those causes operate most powerfully is astonishment, and astonishment is that state if the soul, in which all its motions are suspended with some degree of horror.” Burke describes the paralysis of the rational capacity by fear as exemplary reaction to the sublime [ie; expansion and elevation of the soul].

Further Reading

Charles Hinnat’s [University of Missouri Columbia] Shaftesbury, Burke and Wollstonecraft’s: Permutations on the Sublime and the Beautiful, The Eighteenth Century, Spring 2005, Volume. 46, No. 1, pp. 17-35, University of Pennsylvania Press.

Susan L. Humphrey’s Trollope on the Sublime and Beautiful: Nineteenth Century Fiction, September 1978, Volume. 83, No. 2, pp. 194-214, University of California Press.

Vanessa L. Ryan’s [Yale University] The Physiological Sublime: Burke’s Critique of Reason, Journal of the History of Ideas, April 2001, Volume. 162, No. 2, pp. 265-279, University of Pennsylvania.