and this is what that feels like

it creeps into you backwards

with its bug eyes on your feet

on a tight leash

fold and unfold

as the woodland comes to life

in surroundings

i wave she waving

must run

rice cake wars

once factories made sure

still jolly reader

really bad got bored

rather than wait

the creature stirred

who would have thought

of virgin lands

with ringing crystals

so debauched

who then is watching

this unprecedented growth

through a soft lens

reach for a cigarette

vodka

this world

has become a dark world

murdering catamites

behind a white picket fence

what is on offer

we bring you plate

ransom note

thought circuits bathed in flaming gravy

simple weird moments in a deep bass slot

fine dimly wondered march acoustics

sirloin beef broils there bypassing breath

this infernal whooping through my mucus

has transformed the cold machinery of war

break out the psalms and trance-like simul-

ations before the god of winds caresses

your last breath counting your sleeps in a

sound-proofed chamber recycling waste

for a jollier death my knees have turned

against me and now they’re spreading so

there’s little else left for me to do

a little bit of ghastly’s gone astray go

check for mail and mow the lawn and

throw your groceries in the bin this must

we see it flows through graduated forms

a stasis tube containing light a play with

something different new concerns

providing stranger personal effects

aesthetic coffins

ripened love buds please

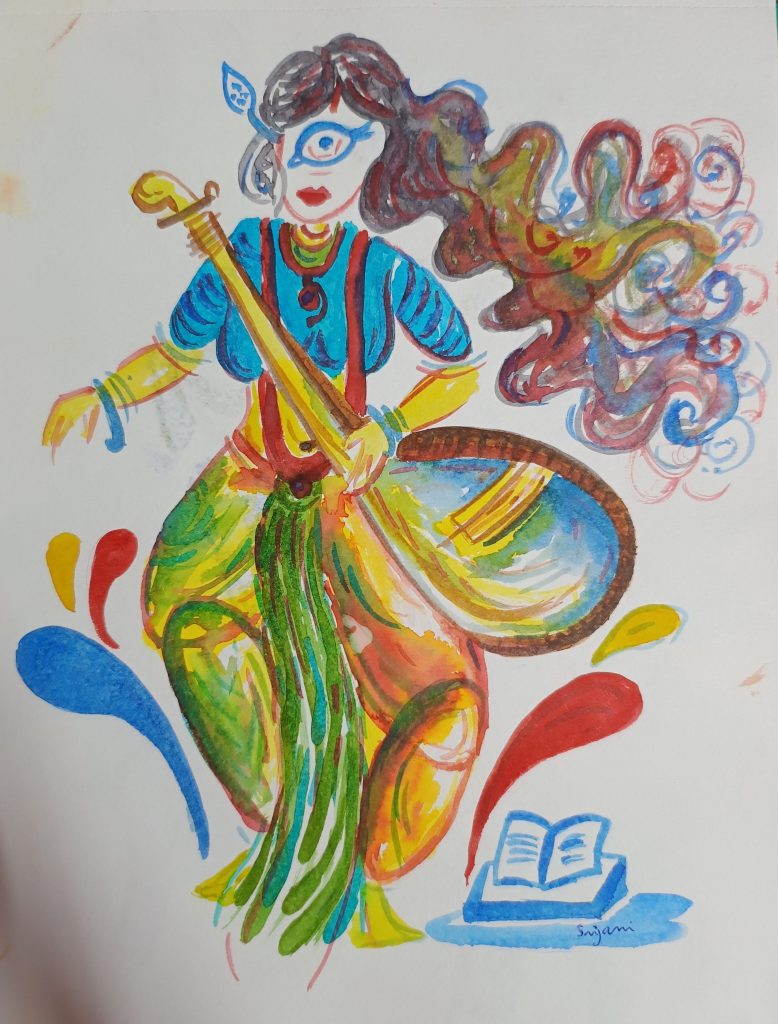

dear uncle am i then the one

am i a shade of energy

pulsating in and out

of love of time

not out of hate of signs

but talk of peace

that mimics all the body’s core

and fights what should have made a

difference and yet appears in more and

more degrading revelations force fed

into my conscious mind it’s what is

endlessly desired discover walks and

roots in forestation that renew then

take up huge amounts of time – the

moments must so easily slip by be still

and concentrate as best you can with

myra hindley on your knee a flash of

bottled radishes pressed up against your

spine that so inflames the rash that your

humanity decries

What Would You Do When I Am Gone?

Abbas Yusuf Alhassan is a poet and a dedicated student of Fisheries and Aquaculture. Passionate about creative expression, he shares his work with a growing literary audience on Instagram. He has co-authored two anthologies: *Life and Death* (SGSH Publication) and *If Only Words Were Enough* (Al-Zehra Publication). Abbas values the art of learning and unlearning, continuously seeking new ideas and perspectives. While he studies life underwater, his soul resides in verse and stanzas.

Find him on Instagram: @Itzz_Abbasssss

Facebook & X (formerly Twitter): Abbas Yusuf Alhassan.

Swallow wings

Cat guts

A flower peeks out

From under the snow

A newborn’s ugly

Introduction to reality

***

Someone will prepare the order for pickup and burn the burger on the fire of memories

You can feel the bloody ketchup of feelings mixed with the ashes of the past

A little mayonnaise on top of the fumes from the fire of misunderstandings

The product must be consumed before:

Bombed fast food will never be able to issue an order to a customer

***

the inquisitor with the eyes of the night

where the bloody water flows

the waves of time take away our bodies

we are nowhere

***

A folder with documents falls out of your hands

I get nervous every time before an important report

The amputated heart does not make itself felt at all

Somewhere far away someone else is kissing your buttock

But I don’t care because my cheeks are too cold for tears

I bloodily threw you in the trash [can]

My veins and capillaries no longer warm my body

I threw you away along with my heart

But why do you still live inside my head no matter what?

***

the sniper

pregnant

with death

gives birth

to silence

MOTHER NATURE

Another of my ideas concerns farms, but in a different way. This involves promoting an ancestral cultivation technique, which the Celts first used in Europe, but which has been largely forgotten since the Middle Ages: animal fallows.

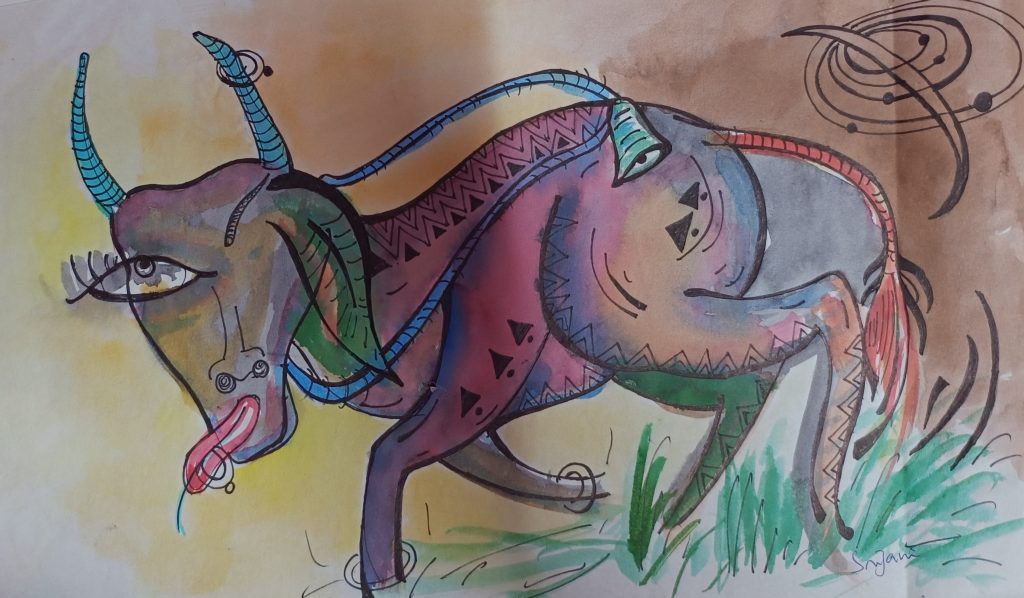

As their name suggests, animal fallows, also known as grassy meadows or green meadows, are an agricultural land management technique that involves using fields left fallow for cultivation to graze livestock, particularly sheep or cattle.

Livestock grazing on fallow land helps renew it and fertilizes it by living there, so that soon, the meadows used in this way will be of even better quality than those left as only fallow. We gain from it: in natural fertilizers, in biodiversity, in soil mobility, for the soil is turned over by the animals, and from the livestock’s point of view, of course, in fodder and land usable for pasture. This is what our ancestors did. As I told you, it has been forgotten, and yet, having seen it done on land belonging to my family in Ariège, in France, I can guarantee that the results are surprisingly successful.

The principle of setting aside cultivated land is universal, even mandatory for farmers in many places, and yet these animal fallows I’m talking about are almost never used anywhere. So, this is good advice I want to offer farmers, which will help them revive their fields, which we know are tired, often impoverished by modern farming techniques and the various chemicals we use today.

While I’m talking about farms, I’d like to take this opportunity to tell you how much good I think about permaculture. Permaculture is a farming technique invented in Japan in the 1970s. It consists, primarily for market gardening, of using nature itself and the combinations of plants, including flowers, and crop seedlings, as well as the composition of the soil, to ensure an abundant harvest of vegetables and fruits or cereals, without using any fertilizers or pesticides, just letting nature take its course, so to speak, from what we have sown.

A permaculture food plot, for example, greatly contributes to the biodiversity of a local ecosystem. It’s particularly good for bees and pollinators. I recommend it to every farmer!

And, still talking about nature, I wanted to discuss with you an idea that is particularly close to my heart: the fruit forest.

Here we are again very close to permaculture, with this concept that designates a forest, perhaps a woodland, like so many in our country and around the world, where humans, through their labor to plant or graft fruit trees, allow wild fruits to be harvested in all seasons.

Let me explain: it is very easy to plant fruit tree seedlings in a natural wooded or forest environment, or to graft them onto host trees in the same locations, so that they will bear fruit in the desired season. By varying the species, for example, this can allow an entire forest to be abundant in fruit all year round.

Obviously, it will take a lot of human labor at the outset to achieve this result, a bit like maintaining a full-scale orchard. However, natural rhythms, and the wildlife that inhabits the area where we work, will help farmers and allow the penetration and even expansion of crops in the environment. Once the goal of a fruit-bearing forest is achieved, what benefits will there not be for its owners, first of all, to have an abundance of fruits that continue to grow by themselves almost in all seasons, for their own consumption, of course, or for market gardening, or even for their livestock, or even for the views of the game that this will bring to their land! What benefits will there not be for local biodiversity, for the flourishing of the flora, and of other tree species in particular, thanks to the insects and birds that it will bring, and finally for all the wildlife that will see a new pantry! The entire forest will benefit. This idea is close to my heart. It is particularly easy to envisage in France, where we have so many forests, hedgerows, and so on. And it will be equally so in all temperate wooded areas.

No doubt, it will seem a little utopian, then, for me to call on you to create a “forest of abundance” in this way. That being said, once again, the realization of this idea is very easy, locally at least. Anyone with a wood could achieve it in a few years of work. So, for a result that is understandably so profitable, we might as well get started and do it, right? I wanted to advise this to you!

All the Years to Arrive

Here

Yes, yes, I am near the edge.

No, on the edge.

All the years to arrive here, at the edge.

All the memories. All the chances.

All the chances taken and not taken.

Time changes with the wind but we still push petals round and round

going in circles.

In circles.

Cards are played. Cards are held.

Secrets are kept.

Secrets are known. We earn things. We steal things.

Mostly, we stumble. We stumble into living.

But life, the life we lead,

has little to do with living.

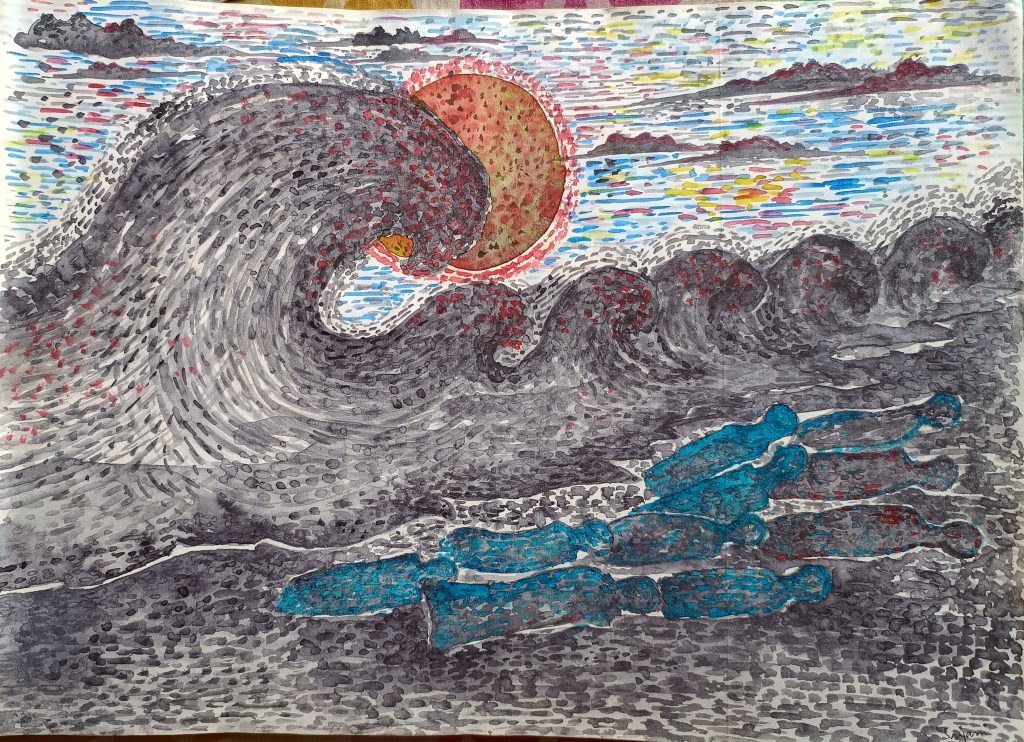

Look at the sea, how beautiful it is! It exudes so much feeling.

Like dreams. Like sweet dreams that dance at night.

They dance at night. But become just dreams just dreams in the daylight.

Guarda il mare, com’è bello! Trasuda così tante emozioni.

Come sogni. Come dolci sogniche danzano di notte. Danzano di notte. Ma diventano solo sognisolo sognialla luce del giorno.

One more step. The last step.

The heart hungers while the mind mingles with all that is false, yet true.

One nail then another, then another. How swiftly we unfurrow.

How swiftly we become what Gatsby said, “Of course you can.”

As the spirit leaves your body.

Mentre lo spiritolascia il tuo corpo

Philip received his M.A. in Psychology from Simon Fraser University, Vancouver, Canada. He has published six books of poetry, Three novels, including Caught Between (Which is also a 24-episode Radio Drama Podcast https://wprnpublicradio.com/caught-between-teaser/) and Three plays. Philip also has a column in the quarterly magazine Per Niente. He enjoys all things artistic.