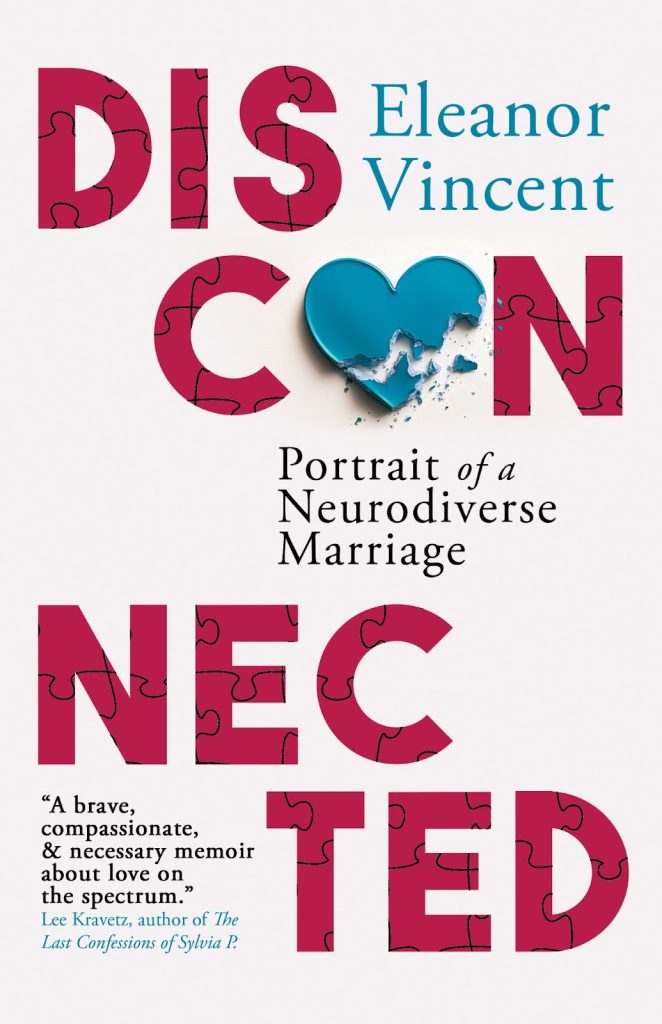

In Eleanor Vincent’s latest memoir, she quotes a therapist who describes marriage as a joint project both partners need to look after, like a puppy. The “puppy” becomes a third character in Disconnected. Eleanor and Lars both have individual life stories, but as they interact, the partnership takes on a life of its own.

The story follows her late-in-life relationship: meeting, dating, breaking up with, reconciling with, marrying, and ultimately divorcing Lars. Bits of backstory or asides that inform the present but aren’t quite long or relevant enough for full chapters get combined into “Things I Left Out,” in each of the memoir’s three sections.

These asides, and short chapters, fill out Vincent’s story and reflect her willingness to do self-analysis and examine her background and her relationship in full. Vincent describes where she lives, a “wealth-adjacent” SF Bay Area suburb, near things she likes: trees, order, quiet. She acknowledges that her surroundings might represent the peace she craved growing up in a high-conflict family with an abusive father and parents married to each other to conceal being LGBTQ. On a smaller scale, we see how her psyche and childhood background give her a need for order inside the home. This helps us understand why staying tidy and organized is important to her, and how it becomes a conflict with Lars and his need to feel secure by holding onto things.

She also does some work to understand Lars by talking with him as much as he will allow and reading up and joining support groups for partners of autistic people. She shares information she has read about how many autistic people think and feel and applies that to her husband. Her efforts to understand his point of view and his preferences give the book depth and fill out the story so it’s the tale of a marriage “puppy” rather than a lonely wife’s monologue. Other societal issues, such as age discrimination, further weaken the fragile “puppy,” as they can no longer afford marriage counseling when Lars gets wrongly fired from work.

Vincent varies sentence length and starts chapters at points of dramatic tension, then fills in backstory to catch readers up to that point. The whole book isn’t overly long, but covers an entire relationship’s life cycle. It includes bits of humor amid tragedy, usually through witty after-the-fact observations. For example, Lars would go silent or discuss random scientific facts during moments of tension. Once, desperate to be heard, Vincent beat his chest, then brought them both inside her place so that “the neighbors would not see the spectacle of an old woman beating up Bill the Science Guy.”

Disconnected is one story of one marriage with one autistic person involved. Eleanor and Lars do not represent every mixed-neurotype marriage out there, and Lars is not like every autistic person. While Lars does share some traits with many autistic people, everyone’s experiences will vary. Vincent conveys this through focusing intently on her own life and relationship for the first two-thirds of the book and only bringing in information on autism near the end as part of her desperate journey to understand Lars. This highlights that this is a memoir, not a textbook illustrating the inevitable struggles within all intimate relationships with autistic people.

As Vincent mentions, many experts now say that we should think of autism as a different neurotype with strengths and weaknesses, like a different and equally valid culture, rather than as simply a less able version of the neurotypical brain. And Lars shows some solid strengths: in situations where social expectations are cut and dried, he can navigate a whole room with ease, he is excellent with travel logistics and phone repair, and a gifted zydeco dancer.

Still, while the neurodiversity model may make sense on a broader cultural basis, and a human rights basis, if a particular person is in a situation where they need to do things to function that are difficult for their neurotype, they (and those close to them) can experience autism as a disability. And Vincent underscores how it’s important to honor people’s personal experiences and struggles without judgment, which would apply to autistic people as well as their neurotypical relatives.

As Vincent painfully discovers, sometimes love and the desire to make a relationship work is not enough when varying neurotypes present clashing emotional needs. And sometimes there isn’t much one person can do when their partner has already given up and checked out of the relationship. Sometimes people are just better off apart, and it’s best to separate with dignity and let the “puppy” go to a good home elsewhere.

Eleanor Vincent’s Disconnected is available for order here.