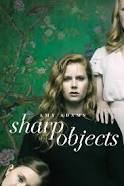

Sharp Objects: Redefining Post-sexual Bliss

By Jaylan Salah

Even 40 years later, Laura Mulvey’s “Male Gaze” theory on the voyeuristic pleasure of cinema is still valid and applicable. In 2018, television audiences and feminist critics alike were treated to one gem of a miniseries titled “Sharp Objects”. Originally a book by Gillian Flynn and recently an HBO mini-series directed by Québécois filmmaker Jean-Marc Vallée, “Sharp Objects” takes an anti-heroine and puts her back in the heart of where all her trauma started; her small hometown Wind Gap in Missouri where women are still viewed as town sluts or doting mothers, men brawl and charge at women in the disguise of false machismo, wealthy tycoons rule the fates of others and demand the welfare of lower class families. In short; Wind Gap is Hell and it is only complicated by our protagonist’s own baggage of family abuse and sexual assault.

Camille Preaker is your next anti-heroine; not the way Angelina Jolie played it in “Salt” or Helen Mirren glamorized it in “Prime Suspect”. Preaker is a mess. Sometimes you wonder how she manages to hold on to dear life with a dozen of problems; alcoholism, casual sex, self-harm and emotional trajectories are examples of personal bullets she tries to curb at every turn. Preaker is not how Sophie Gilbert from “The Atlantic” wants to see female journalists depicted on-screen. She drinks on the job, sleeps with possible sources and barely takes notes. Gilbert describes that as being “far from reality” and compares Preaker to a much more composed female journalist character as seen in a Showtime documentary. In other words, Gilbert plays the same mistake male reviewers have been associating with female characters that simply do not fall into line. She’s unlikeable! She’s unprofessional! She’s a bad feminist influence! It all falls into the “trope” which –despite capturing the inadequacies in the past era of creating female character clichés– placed nonlinear female characters side-by-side in fear that they might be a trope (hint: throwing every quirky female character down the Manic Pixie Dream Girl abyss without proper analysis of the character or even the creative medium from which she emerged).

Camille Preaker is one of the least sexualized female characters on-screen. She is rarely seen without clothes on and when it happens; it is meant as a tool of provocation rather than arousal. What makes it the more compelling is casting a stellar actress such as Amy Adams who has shown her sexual, seductive side successfully in more than one film to portray a non-sexualized character who is completely covered in self-inflicted scars. Preaker is an angry female that would make John Cassavetes’s Mabel Longhetti proud. She displays the same vulgar, unethical alcoholism that the likes of Don Draper in “Mad Men”, Dean Winchester in “Supernatural” and Hank Moody in “Californication” boast as if it is a character trait rather than an addiction that requires immediate intervention.

Preaker is no Veronica Mars or Buffy or Rory Gilmore. She embodies the ultimate feminist fantasy of having an unlikeable woman grace the screen and reach…nothing. Even her crusade against her dominant, abusive mother –played to perfection by Patricia Clarkson– led to nothing but a rather harrowing discovery in which we -as viewers- are left in mid-sentence, unable to expect what might come ahead.

Director Jean-Marc Vallée creates an ominous presence of Camille’s suffering; his angles, his tracking shots of Camille driving through the dead Wind Gap scenery. His gaze unrelentingly shows her at her most vulnerable, non-sexual self, even throughout her most sexually traumatizing memories (i.e. her gang rape). One of the most notable moments of the series involves how Vallée flips the Gaze by paying homage by creating an anti-traditional post-sexual bliss scene.

Post-sexual bliss scenes pose a recurrent theme in movies. It is usually a justification to show a naked -or semi-naked woman without having a key plot moment that involves nudity. Take “Entrapment – 1999” where a sexually undesirable man (69-year-old Sean Connery) is caressing the body of a much younger, sexually appealing woman (30-year-old Catherine Zeta Jones) draped suggestively under the sheets. Male fans’ reviews back then show how the box-office sensational, testosterone-pleaser was an unapologetic, successful malefest. At least that’s what Joe Chamberlain on Google Groups think,

“This may sound a bit sexist, but here goes. As far as I know, the main audience for an action movie is young males. So it seems perfectly reasonable to me to cast a young, very attractive actress in the leading role.”

The scene where a fully clothed Connery caresses the body of an actress young enough to be his granddaughter, throws back a shade on the infamous scene from James Bond’s Goldfinger where a much younger, much sexier Sean Connery is seen caressing the naked, gold-painted body of a typical blond (dead) Bond casual fling. In the now iconic sexist/sexy scene, the dead girl dies after being painted completely in gold, the main protagonist -Bond- simply caresses her strategically placed naked dead body. And audiences are not supposed to mourn or feel bad for the hot girl whom they just met a few minutes ago but to revel in the immaculate beauty of a gold-plated naked female corpse.

In “Sharp Objects” Preaker is fully clothed, while Richard –Camille’s object of affection throughout the series and the Kansas detective who investigates the grim murder cases– is lying seductively naked on the bed. As Preaker caresses his naked body, desire apparent in her voice, viewers are greeted with a naked object who has a voice and a say in what is being done to him. With women, though, the camera treatment begs to differ. In “Goldfinger” that would be impossible since the naked object is a dead girl, while in “Entrapment” Sean Connery caresses the naked body of Ms. Jones who pretends to be asleep. In both cases, the male psyche and subconscious are being lured into the movie theater to see a semi-naked silent female object being fondled by fully functioning male protagonist.

In her refusal to be seen, Camille Preaker strips the gaze off its power to hold an object within its focus. Instead, the focus is on Richard’s naked body, on whom her Gaze lingers with longing lust, and on which the camera lingers as well, allowing audiences to feast on male nudity for as long as the scene lasts.

Any photographer worth their accolades can write essays on the vulnerable nature of the nude object. And now, for the first time in probably a decade of TV shows where sexuality is a key element in the main plot, men become vulnerable and nude while women remain fully clothed, in charge and changing the sexual power curve, at least physically.

Pingback: Synchronized Chaos February 2019: Telescoping View – SYNCHRONIZED CHAOS