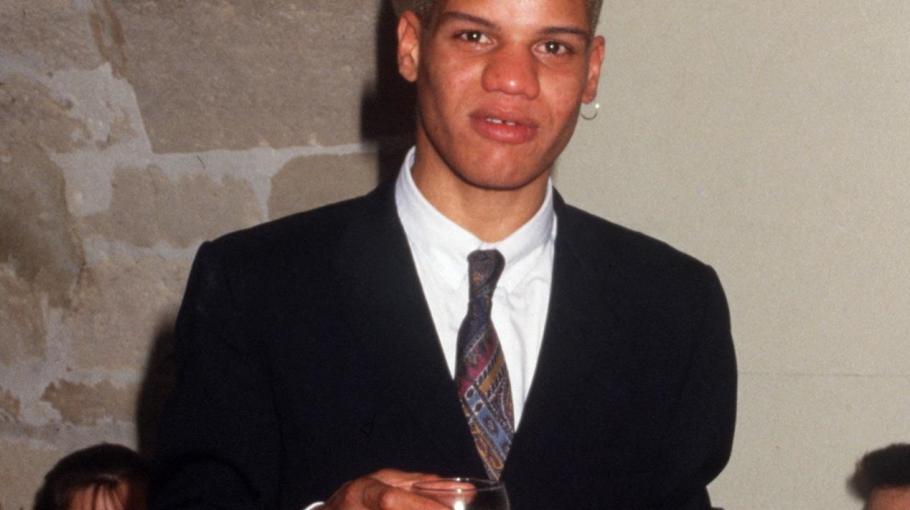

Why (Do) White French Institutions Have a Hard Time Admitting The Impact Of Racism/Colonialism In Black Serial Killers' Psychological Damage?: The Case of Thierry Paulin France's most notorious serial killer was a black man. Thierry Paulin. Born in 1963, in Martinique, the young man left the earth at only twenty-five, leaving behind him a horrific legacy. Between 1984 and 1987, the year of his arrest, Paulin murdered twenty-one old ladies in Eastern Paris to steal their money and fund his lavish lifestyle. However, though he admitted to having murdered twenty-one old ladies, the French police had enough evidence to suggest he would have actually killed up to forty of them, with a total of sixhundred attacks and theft. Thierry Paulin and Guy Georges are still the only two Afro-descendant serial killers in France to this day, a nation whose phenomenon of mass murder is still rare. Both men share the same background, were mixed-race, abandoned by their parents, evolved in a white French conservative society which rejected them for being Afro-descendants and did not have (a) place in psychiatry to treat their specific conditions. If a few documentaries were made about Paulin, and a few books were written about him, only white people were behind these projects. In the tradition of the French media in the 1980s, they did not approach Paulin as the failed human being he was, but as an animal exposed in a freak show from whom any institutional power wished to exploit for their own gain. Indeed, in the 1980s French society, a time when Black people were even more invisible, the arrest of Paulin appeared as a surprise. In that sense, the French journalists, not only exploited the killer and the victims to feed sensationalism, but they also needed to further and create the image of a monster who had appeared from nowhere in French society to attack innocent white old ladies. In all the articles written about him by the journalists and experts, Paulin was introduced as a total enigma, when his downfall was never shrouded in any mystery, as it rather took root in a specific side the French institutions did not want to dive into. Thierry Paulin highlighted the hypocrisy of French society, whether in justice or law, regarding the treatment of Caribbean groups in the postcolonial migration waves which started massively in the 1960s. None of the journalists who attempted to focus on his history ever talked about the brutality of the Caribbean experience. Indeed, Paulin's fall into mass murder was directly linked to and caused by the tragedy and the failure of the Afro-Caribbean immigration experience in France at that specific time. Upon studying his case, the medical institutions even failed to understand the structure of Caribbean families - especially when it came to family abuse inherited from slavery - in order to evaluate the damage it had caused in Paulin's psyche. In the racist white French landscape of that time, Paulin had to remain this freak, light-skinned, mixed-race, young gay mass murderer and occasional drag-queen, who had suddenly decided to crush the lives of innocent and helpless old white women. Therefore, if a few modern white journalists have tried to understand the mind of Paulin, they still refuse to focus on the impact of racism, the Caribbean immigration experience, poverty, social isolation and psychological damage of the black mind. First of all, this hypocrisy of the white French institutions can be explained by history itself. Though France was always a great colonial power which greatly contributed to the Slave Trade, the French authorities are no stranger to the black body. Yet, contrary to the Northern European white colonial powers which furthered the concept of apartheid, through racial separation, Latin powers such as France rather focused on the idea of universalism, métissage (race-mixing) in order to annihilate any revindication from the colonized groups. As a consequence, if the French institutions do not recognise the differences in races, due to this principle of universalism, then racism can not be a valid argument when it comes to the damage of one's black mind. This hypocrisy helps the French institutions to reject their role in colonialism (and) slavery since they can hide behind the principle of universality. Thierry Paulin never had the possibility to be diagnosed, understood and perceived for who he was, due to the policy of universalism. Neither the media nor the psychiatrists wanted to know the truth but rather wanted to exploit Paulin for him to fit in their own pre-conceived ideas regarding the murder. Paulin did not kill because he was a born-killer or a born-beast, but was psychologically and mentally ill. Yet, such approbation of his mental health was not pushed at the forefront by the media as the journalists only highlighted any degree of sensationalism. When interviewed by racist psychiatrist Serge Bornstein in 1988 and in early 1989 before he passed away of AIDS in his hospital-prison cell of Bichat, Paulin was described as arrogant towards the medical staff. In reality, a narcissist, he knew the scheme which was being displayed before his eyes. All wanted to exploit him and he refused to give them any secret, especially from his childhood. Yet, one thing should be mentioned. If the judiciary and political institutions promote the idea of universalism, such ideology exists in medicine, especially in psychiatry. Though this sector claims not to see race and differences, the French medicine was based upon colonial and racist principles which date back to the Enlightenment era in the 18th century. Later, cases such as that of the Venus Hottentot whose remains were kept and exposed until the 1970s, would illustrate our argument. The black body in French medicine is invisible, and such reality comes as even more shocking since France has been a great colonial power. In that sense, Paulin was given techniques of analysis which were made and conceived for white male criminals. Paulin, as a mixed-race Caribbean young man, was the product of another reality which is that of the impact of slavery and French colonialism on the Caribbean societies and thus, in families. If the impact of the slave trade and its oppressive system were to be recognised, the French societies should have been forced to acknowledge that Paulin, just like Guy Georges, were not "monsters" born out of nowhere, but the pure products of France's historical, social and political failures regarding the treatment of black minorities, whether mixed-race or not. Paulin's mind was never analyzed by a black psychiatrist, but rather by incompetent white French psychiatrists who had no knowledge of black Caribbean societies at all. Both the psychiatrists and media refuse to admit that racism, race and black historical oppression can not only destroy a family's structure but also weaken the mind of a black individual living in the Western sphere. Thanks to social media, more and more black women in France took to Twitter to denounce their mistreatment in French medicine. Most of them had been the victims of the Syndrome Méditerranéen (translated to Mediterranean Syndrome). The latter refers to the constant mistreatment of black patients whose symptoms of pain are not initially believed to be true by the white doctors who are in charge of them. The group members are, through prejudice, always said to lie and exaggerate their pain. In 2017, French-Congolese Naomi Musenga lost her life for this reason. As she was suffering from a hemorrhage, she called the SAMU and a white female dispatcher mocked her and her symptoms, refusing to take her seriously. The young lady eventually died of her inner pain and struggle. The medical structure at the time of Paulin was not only late, but never studied Paulin's dysfunctional family background, his mother's psychiatric identity or even thought of understanding him through the Caribbean experience, as they rather chose to remain focused on their racist views, using the brutality of the murders to support their diagnosis. On the contrary, in the United Kingdom, another great European colonial power, white psychiatrists had written reports, as early as the late 1960s, to alarm the health government on the risk of schizophrenia on Afro-Caribbean patients linked to racism, the trauma of isolation, poverty and the effect of a double identity. But France, which was always late, even when it comes to the technique of DNA, did not study its minorities at all. Paulin was thus presented as a brutal individual, when his crime history follows the pattern of a crushed Afro-Caribbean man who failed to find a place in a white French society which did not want him. The constant abuse from his family, whose members rejected him, weakened him deeply. He suffered from severe depression as a result of his parent's abandonment, hence a mental disorder which was never addressed. He never found any institutions in his youth which could have helped him heal his mental disorder and rather carried on reaching the lowest levels of his own self. He gradually became suicidal, psychotic, became a sociopath and eventually a psychopath as soon as the crime frequency increased. Paulin was not born a monster, but rather was the product of both black Caribbean and white French sociopolitical failures. Just like Guy Georges, Paulin could have been saved and possessed all the resources necessary to make it in life but he was failed in his mental state until he committed the worst. Paulin was, before anything else, a mentally ill individual who had inherited important psychological issues which are not mentioned by the French media until this day to further the racist description they made of him. The case of Paulin also helps us note one thing when it comes to the absence of black psychiatrists. Two years before Paulin was born, Frantz Fanon passed away from leukemia at the age of thirty-six. He remains, until this day, the only black Caribbean psychiatrist to have written about the impact of colonialism on the black mind, while the Black Americans had W.E.B. DuBois as early as the beginning of the 20th century. This highlights the lack of interest of white French institutions regarding the case of black psychiatry, especially when Western medicine has been tied to the capitalistic value of the minorities in the spectrum of raw capitalism. Paulin fascinated in the morbid experience for what he portrayed and not for how complex his psyche had become. There was, from the white psychiatric group, no desire of healing, understanding in order to repair any damage but they rather fed their egos as they hoped Paulin would correspond to their pre-established, fraudulent diagnosis. If the worst white French and Belgian serial killers and paedophiles were deeply analyzed even in their most repulsive actions, Paulin, a black Caribbean killer, never received such a privilege. The latter had to be exploited for sensationalism only and sexually deconstructed. If Frantz Fanon remains the only black Caribbean psychiatrist to have written about the colonized black subject in psychiatry, one problem exists regarding the silence of Paulin's community. Not one single black Caribbean intellectual, whether Aimé Césaire, Edouard Glissant or Maryse Condé, spoke out to explain or attack the media in their racist treatment of Paulin. The Caribbean community still refuses to speak on it. This silence can be understood by their history and immigrant status. At the time of Paulin, the Caribbeans had been bred to submit, fear and not question the white French authorities at all. They had no political power, no economic presence, and had massively arrived through the colonial programme which was the BUMIDOM. The Caribbeans were bred and raised to live through and for the white French gaze only. If all of them knew the real reasons behind Paulin's motivation to kill, they would choose to turn a blind eye. Plus, the homophobia of these French Caribbean societies did not encourage the members to speak on the Paulin case, thus explaining their distance from him. Yet, Thierry Paulin is not 1987. He is the 1990s, the 2000s, the 2010s, the 2020s, will be the 2030s, and 2040s as long as the questions regarding the status of the ignored Caribbean community in France is not brought up. Indeed, the Caribbean youth, decades after Paulin's death, still have to deal with the same treatment endured by their forefathers. They remain isolated and their social problems, including that of food poisoning through chlordécone, are voluntarily hidden. And though the years went by, the treatment of black patients in psychiatry is still nonexistent. As a consequence, France is not protected from the sudden emergence of a new Paulin in the years to come.

VK Y

(previously known as Victoria Kabeya)

French-Belgian author and historian of African and Middle Eastern heritage. Born in France, 1991, she began her career in 2015.

As a scholar, Kabeya’s work evolves around postcolonialism through art (mostly rap French music), the study of the Sicilian/Neapolitan subject in postcolonial Italian society, Blackness in the Arab world (Israel, Palestine, Syria, Lebanon and Iraq), the Afro-Caribbeans and Indigenous Natives in Latinized America, Race-mixing and the consequences of psychological trauma among young Black boys in the ghettos.

Purchase: V KY: libros, biografías, blogs, audiolibros

Read: VK Y, Victoria Kabeya

Thank you very much Sync Chaos for your trust ! I enjoyed writing it for you ! Keep up the good work !

You are all amazing !

Kind regards to all

VKY- Victoria Kabeya <3