Cinema uses politics and history to produce meaning just like a literary text does. Explore this idea with respect to any literary text and its corresponding film adaptation.

Nostalgia films embody historical picturesque adaptations that represents nostalgic fetishization of authenticity. Laura Mulvey film critique points out that “stylized and fragmented by close-ups…as the direct recipient of the spectator’s look”. Miss Havisham conferment of jewels upon Estella’s breast and hair was the symbolic travesty of objectification of the female body into delectable pieces for male consumption; therefore exhibiting and showcasing Estella’s feminine body politic as an object to be treasured, owned, memorialized, fancied, toyed, desired and possessed. Similarly Miss Dinsmoor exposes Estella as the embodiment of artistic consumption; foreshadowing the perilous commodification of selfhood upon which the bildungsroman hero Finn will focus his expectations in the Manhattan studio.

That Miss Havisham’s portrayal of transmogrification as incarnate of Dinsmoor infiltrates the filmic Satis House -the domicile of family brewery where Miss Havisham’s father produced the family’s wealth; economic designs penetrating marital relations as Miss Havisham was jilted by her lover Compeyson and the kinsman Arthur. Fallen and unfruitful paradise: large and dismal house barricaded against robbers. Thus though ‘Satis’ is the root of satiation and satisfaction become inverted into unsatisfaction and undernourishment of a barren wasteland. Dickensian descriptive language resonates bizarre eccentricity of the archetypal spinsterish lady. She [Miss Havisham] has never allowed herself to be seen doing either…She wanders about in the night, and then lays her hand on such food as she takes”.

Miss Havisham’s bridal feast commemorates a black fungus on the table where speckled legged spiders with blotchy bodies infestation occurrence ; and this rotting bridal cake metaphorically personifies Miss Havisham’s moral decay: anthropophagy revealed by the cliche: “The mice have gnawed at it[bridal cake] and sharper teeth than teeth of mice have gnawed at me”. The gothic imagery of the body and the market dynamics of Miss Havisham coalesced with the incursion of the financial world into the domestic hearth as Miss Havisham’s cousins wait to feast on the same table where the spiders feed upon her bridal cake. Miss Havisham adopts Estella who establishes sense of proprietorship in the bildungsroman hero; Miss Havisham later deals in trafficking of children instead of wine; albeit the Satis House becomes the economic nexus for the grasping members of the Pocket clan. Miss Havisham characterizes the transparent fawning of her relations as the grossest consumption, ripping the table with her stick saying: “Now you all know where to take your stations when you come to feast upon me.”

The mourning masks and the mourning jewels such as brooches and rings are grim simulations of grief and death portends the bildungsroman hero with the inherent liminality of capitalistic culture that is built upon the sufferings of the poor wretches such as the castaway Magwitch, the clandestine patron of the protagonist.

In terms of mise-en-scene the most striking contrast of the dark and the light imagery in the cinematography studies shifts film and movie audience away from the dramaturgy in novelistic adaptation. Revealing the departure scene as the epitome of the halcyon farewell in the filmic production, the hero and heroine are beneath the bridge; the camera tracking the hero as Finn walks back into the sunlight while Estella’s image disintegrates into a dark blur in the background. Extracted quotable quote illustrative of the Dickensian rhetoric used in the semantic approaches to the semiotic is thus read: “….in all the broad expanse of the tranquil light…no shadow of another parting from her”.

Estella’s reunion with Finn at the bright sunlight sea suggests the amorphous relationship and the future possibilities; there is no retreat in the darkness of the heroine tempered by motherhood and divorce; brought the daughter to view the ruins of the childhood estate of legacy. In textual and filmic language the authenticity has been intact although the mise-en-scene diverts away from Estella’s realistic characterization by Charles Dickens as the virgin, angelic, haughty, heartless, thankless, damsel beauty separated from her deceased life partner the snobbish extravagant loutish of the Finches Groove. Dialectical approaches to Dickensian film criticism would authenticate the valedictory speech act in the character of the bildungsroman protagonist and his heroine as limelighted in these exchanges:

[narratorial authoritative imperative and Estella’s declarative:… “everything else is gone from her [Estella]. The silvery mist is touched by the first rays of moonlit and the same rays touched the tears that fall from the eyes. The ground belongs to her…”It is the only possession I[ ] have not relinquished. Everything else is gone from me, little by little, but I have kept this…

[autobiographical bildungsroman protagonist’s voice: “Estella, to the last hour of my life, you cannot choose but remain part of my character, part of the little good in me, part of the evil.” In terms of intertextuality Wuthering [Cathy: I am Heathcliff] can be paralleled in the bildungsroman hero subverting the conventions of romance love making speech associated with objective identification by directly merging his subjectivity into the heroine : “every prospect I have ever seen” ideally “the embodiment of every graceful fancy that my mind has ever become acquainted with”.

Further Reading

Shari Hodges Holt’s Dickens from a Postmodern Perspective: Alfonso Cuaron’s “Great Expectations” for Generation X, Dickens Studies Annual 2007, Volume: 38, pages: 69-92

Gail Turley Houston’s Pip and Property: The [Re]production of the Self in “Great Expectations”, Studies in the Novel, Spring 1992, Volume 24, No. 1, pages: 18-25

Keith Easley’s Self-Possession in Great Expectations, Dickens Studies Annual, 2008, Volume 39, pages: 177-222

Susan Grass’s Commodity and Identity in “Great Expectations”, Victorian Literature and Culture, 2012 Volume 40, No. 2, pages: 617-641

For young people living in the world of adults, “love” is a means of defiance and resistance. Explore with respect to the literary text and any cinematic adaptation of Romeo and Juliet prescribed in your course.

The frantic pace of the movie reveals the outburst vehemence and impulsive hot-headed nature of the dwelling aboriginal of Verona as latterly foreshadowed by the rage, grief and passion of the feuding rivalries between the adversaries-Capulets and Montagues—-true to the authenticity of Shakespearean spirit. 1960s film version was focused on tragic love; the 1990s is about violent love. Shakespearean dramatis persona were the milieu of the starcrossed lovers and their inner moral dilemmas of those minds whose temperaments resonate reckless and hasty nature as the dysfunctional world of the Montagues and Capulets whose blood and honour were inseparable. Modern day mise-en-scene of the adaptation is a brilliant spectacle that marvels the accomplishing achievements through bestowal of laurel wreathed bouquets and accolades. For instance, Mercutio’s raving in the Capulet’s ball makes unimpeachable exemplary phenomenon with the bottling of acid beforehand. Romeo’s decision to end his life with poisonous drugs parallels the lifestyle of violence and addiction. The mafia clans’ fanaticism of religious sentiments as projected by their Catholic vein running through the plot juxtaposes coldblooded aggression as ironically spotlighted by the stereotypical families.

The close shot camera focusing the Shakespearean hero and heroine cloistered by the walls of Verona and confinement by window frame of patriarchal abode respectively. Upon revealing close up shot Zeffirelli’s camera angle moves to showcase Romeo attired in a deep, lilac; a Montague bereft of Capulet vulgarity and ostentation; nonetheless, pill box hat, eyeliner, flawless complexion and the flower exemplifies effeminacy. “A glooming peace this morning with it brings. The sun for sorrow will not show for his head”—–unshaved, unkempt Romeo beside swollen lips and fluffy faced Juliet in the tomb scene is the visual artifice in commitment to the ironical perspectives of the drama. Zeffirelli’s textual interpretation literally elucidates Shakespeare’s highly stylized and emotionally expressive naturalism that bestows weight to the narrative moments like Juliet’s departure epitomizing overexcitedness and emotional disorientation by the state of the physical dizziness. Here, as throughout, Zeffirelli creates a situation where visibility becomes feeling and feeling becomes awareness.

Religion of love imagery foreshadowed by the sonnet dialogue is absolutely superbly visualized filmic adaptation to cherish beneath the connotations of pilgrimage and saintliness: institutionalized and ritualized love-making courtship. The starcrossed lovers romantic love-making sonnet in the background depicted by the imageries of saints, pilgrims and statues brings the abstractest essence of martyrdom, canonization and immortality—the fabulous trappings embodying their history—their personalities and their naivetes, and their uncertainty of each other and the awareness of the social context in which they find themselves in the ignorance of perils. Choruses last six lines musical effect is absolutely inappropriate and unnecessary addition to the cinematic conventions of diegesis hovering between snapshots and painting, documentary and fiction; reconciling the present tense with the past tense of the film, ethical space with that of the cinema and history with story as profoundly replicated in Mercutio’s remark to Romeo is appropriately credible to Zeffirelli’s diegetic: “Now art thou what thou art, by art as well as by nature.”

Further Reading

Sarah L. Lorenz’s “Romeo and Juliet”: The Movie, The English Journal, March 1998, Volume 7, No 3, Teaching the Classics: Old Wine, New Bottles, March 1998, pp. 50-51, National Council of Teachers of English

Michael Pursell’s Artifice and Authenticity in Zeffirelli’s: “Romeo and Juliet”, Literature and Film Quarterly, 1986, Volume 14, No 4, pp. 173-178, Salisbury University

Examine the cinematic adaptation of Pride and Prejudice with that of the literary textuality.

Costume as well as nostalgia films engage the spectatorship through voyeurism of feminine and masculine sensuality as the technique of dramatization and the usage of focalization as revealed in the construction of Elizabeth Bennet’s and Fitzwilliam Darcy’s dramatis persona; whose body language, literary allusions, puns, metaphor, imageries and symbolisms have been layered with sexual connotations; beneath the intentionally solicited experience of repression tat imbues with sexuality: clothing, landscape, piano playing, letter writing and conversation. Evolving the Austenian filmic adaptations into modern cinema from the BBC 1995 television series, You’ve Got Mail, Bridget Jones’ Diary, Bride and Prejudice to the hallmark production of the film Pride and Prejudice 2005, which is critically acclaimed for the filmic grammar that includes: close ups, insert shots, subjective shots, eyeline matches, reaction shots.

The female body politic is fragmented and transmuted into eyes to be admired, her hair locks to be bestowed, hands to be kissed and feet to be touched as exemplified in the case of feminine fetishization in the heroine Elizabeth Bennet portrayed by Keira Knightley. Mr. Fitzwilliam Darcy in the cast of Mr. Matthew Macfadyen, in whom avowed desire for the feminine object is aroused by the romanticism through fantasizing “the beautiful expressions of her dark eyes”—–the recurring symbol of Elizabeth’s charm. The ardent love of Darcy eventually follows melodramatic marriage proposal, a refusal and latterly unexpected encounter at the Pemberley Derbyshire estate; Elizabeth Bennet’s respect, esteem, gratitude and a genuine filial affection for the welfare of Darcy is translated into a reality. […] “it is many months since I have considered her as one of the handsomest women of my acquaintance”. Love and passion have merged together into authentic and relevant feelings; there is no question of impulsive foolhardiness since the breach of etiquette can be valedictorily redressed and the truth be confessed.

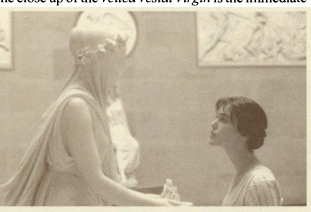

Metonymic love undercover of Austenian body politic is not always translated into synecdochical fragments; sometimes it is also deviated and transmuted into tangible and touchable substitutes of the persona in the marbled sculpture and the mantelpiece portrait found by Elizabeth in the Pemberley Derbyshire estate as transmogrified real metonymical substitute in Darcy’s real picture. Discovery of the treachery and villainy by the janus-faced Wickham is visualized in the narrative perspective: “Till this moment, I never knew myself” is representative of the objective correlativity of the attainment of truth: Mrs. Reynolds, the housekeeper’s testimony of the heroic Darcy’s impassioned defence: “He is the best landlord and the best master […] that ever lived.” Instead of the family portraits the gallery of Chatsworth House offers Greco-Roman antiquaries sculptures such as the corporeity close-up of the Veiled Vestal Virgin in the embodiment of the heroine.

Jane Austen, a subtly pervasive stereotype of defensively ironic genteel spinster wrought by sexuality fogged in bourgeoise morality as opposed to sexual vitality; in favour of frigidity as a standard of sexual conduct. Jane Austen chronicles sexual selectivity behind the wooing and wedding amidst art and nature, feeling and reason, freedom and order, individual and society as thematic plot and dialogue within the narrative. Constrained, reserved, solitary and fastidious Darcy epitomizes vanity and haughtiness, superciliousness and snobbery. Darcy’s inner dramatic dream fulfillment for dancing a reel / “feel a great inclination […] to seize such an opportunity of dancing a reel by the playing of piano by Miss Bingley. Austen stories and characters are brought to life by the landscape and panorama of the settings as wanderings of the exquisite halls and eccentric gardens; drawing rooms pulsating with society’s expectations, gardens consisting of well-wrought urns of mysteries; and the outdoors becoming the witnesses to the silence of the ebb and the flow of love and intrigue.

The narrative moment sedately stroll through parklands and cultivated gardens or accompanied walks to towns is both alluring and perturbing for being unescorted young maidens in Austenian Regency England. In this instance, the heroine walk from Longbourn to Netherfield to visit Jane Bennet: Elizabeth’s hiking over fields, jumping over stifles and springing over puddles aroused the censoriousness in Miss Bingley’s rhetoric of muddy petticoats and blousy hair to which Darcy’s defence of the narrative voice invokes “divided between admiration of the brilliance which exercise had given to her complexion and doubt as to the occasion’s meriting her coming so far alone”, acknowledgement that he does not wish to be allied with a family that frequently makes a spectacle of itself. It is an opposition of heart and head, of reason and feeling, of intellect and emotion, of control and spontaneity, of elitism and egalitarianism—-that Jane Austen ironically insists in satire —-landed gentry view versus the outlook of a gentleman’s daughter.

Jane Austen’s warding off Mr. Darcy’s wedding proposal through the verbal rape of Elizabeth that he has not behaved in a “gentlemanlike manner” is far less explicit than Jane Eyre’s assertion to Rochester that she has full as [much soul as [he] and full as much heart.” But it voices the same feminine complaint alleging the masculinity of unrecognition of the female selfhood. Even after the proposal scene, the antitheses and hostilities between the sexes bear resemblances to Shakespearean lovers in a wood, meeting evanescently for exchanging letters. However, the whole of Pemberley episode is a tour-de-force of technique and perception in which the outward action is a metaphor of inward feeling: “at that moment she felt to be mistress of Pemberley might be something.” The language of speechlessness is bereft of smiles, sparkle of wit and repartee—–Benedict and Beatrice as lovers reciprocated in the depth of the deeper sentiments of silence. Eventually the reticence and resolutions of filmic diegesis of the textual adaptation shifts the pronoun of Mr. Darcy from “I” to “you” in the statements [“In vain have I struggled”… “You are too generous to triffle with me”] to transcend his social and sexual egocentricity. Foiling Georgiana Darcy’s obstreperousness to Lady Wickham or Lydia Bennet heightens the tension harboured by too repressive or too permissive upbringing, each of which equally lead to promiscuity. Through freedom and spontaneity, Elizabeth will teach Georgiana as a corrective to her too rigid upbringing; that she will be a child of Darcy’s head and Elizabeth’s heart, of his principles and her feelings to oversimplify—-of the union of rationality and emotion that their marriage represents.

Further Reading

Roberta Grandi’s [Catholic University of Milan] The Passion Translated: Literary and Cinematic Rhetoric in “Pride and Prejudice” (2005), Literature/ Film Quarterly, 2008, Volume 36, No. 1, pp. 45-51, Salisbury University

Alice Chandler’s “A Pair of Fine Eyes”: Jane Austen’s Treatment of Sex, Studies in the Novel, Spring 1975, Volume 75, No. 1. Pp. 88-103