Sicario: Being a Woman in the Land of Wolves

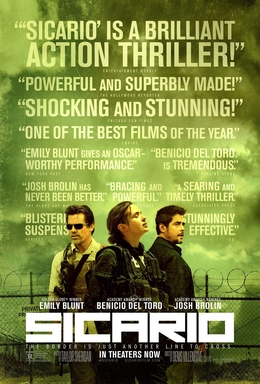

Sicario is a word used in Spanish, Portuguese, and Italian. It means “paid assassin” or “hitman”. As a movie title, it has nothing to do with what this film is about. To make a clearer mental image, imagine using the word “Cannibal” as a title for ‘’Silence of the Lambs” and prepare for 121 minutes of one of the darkest films of 2015.

Have you ever tried to capture the moment and use it as an anchor for what you plan to write?

This is what it feels like while describing what “Sicario” has done to me.

Sicario is a very visual movie, shot by none other than the brilliant cinematographer Roger Deakins who holds films like “Raising Arizona “, “The Shawshank Redemption”, “Fargo” and “No Country for Old Men” to his name. It might come off as another drug-cartel thriller, but “Sicario” reminisces on morality and how the world blurs the thin line between right and wrong, to the point of reaching an utterly bleak endnote, making for one thrill ride. Denis Villeneuve’s film doesn’t leave audiences with a rush of euphoria, but more like a burning sensation at the pit of the stomach.

Emily Blunt brilliantly and ephemerally portrays the role of Kate Macer, an idealist FBI agent who gets thrown into a world of drug cartels, assassinations, cold-blooded revenge, and senseless interrogation scenes. Macer’s world becomes turned upside down when she is chosen to join a task force for the war against drugs, and her whole existence is put on a stake.

How the film plays the female lead’s storyline is very sensitive to the nature of being a woman in the middle of a battlefield. Through her eyes, viewers judge the world she is naively thrust into. Macer explores herself and the male-dominated hostility that surrounds her presence. Viewers are introduced to a unique female protagonist; incapable of senseless violence but tough, humane yet detached. Macer bends the gender roles, she looks for fun through booze, a pack of smokes, and a one-night stand, yet as a woman her priority alternates between getting the job done and saving lives, following procedures, and maintaining a moral ground where there is none.

Villeneuve, with Deakins’s help, creates the tunnel infiltration scene like no other. He introduces audience members to the entire scene through two different perspectives. One is a green-tinted sequence, while the other is an infrared thermal imaging system that created a video game idea of a hunter seeking prey. Shot in black-and-white, where humans appear like negatives on a black screen. No sound is heard. It is just the agents, gun-pointing their way through the murky tunnels. Corpses are shown without a bit of humanity attached, their blood another shade of grey, which deprives the scene of emotionality. It’s an immoral, inhumane world. Human lives are not even questioned whether to be spared or not. How could the viewer sympathize with an action-adventure sequence that could easily play on their Xbox as a first-person shooter via twisted role-playing where they get to be the bad guy (or the cop) shooting nameless, mute targets?

How Macer is roughly handled also shows how disdainful most of her colleagues are towards her mere presence. She is seen as a joke, a pawn used by those hard-knuckled, shady people as means to their ends. When she is attacked by the man she picks at a bar and discovers he wasn’t after her –just using her to get to the big boys behind her- her look of disappointment captures the essence of her experience. The way her eyes register every single violation or atrocity allows the audience to get entangled with her point of view, self-righteous and monochrome at best, yet empathetic and empowered.

Using Macer’s relationship with the sicario, Alejandro –played to perfection by Benicio Del Toro- could be first interpreted based on a mentor taking in a naïve rookie to mold them into the mini-version of that mastermind. Examples that played on this theme vary from Dr. Hannibal Lecter in “Silence of the Lambs” to Detective Alonzo Harris in “Training Day’’. In “Sicario” however, Alejandro doesn’t gift Kate a valuable life lesson or allow her to discover pieces of herself that she never thought existed. They both remain unchanged, she is incapable of violence, and he is amoral –or according to her immoral- and violent, without a hint of doubt or regret.

“Sicario” is a dark poem of practicality that plays out its amorality (or immorality card) with no shame. It prides itself on being brutal, raw, and dark. With excellent performances, a haunting score, and a daunting fin, “Sicario” is not a movie to watch but to watch out for.

Jaylan Salah Salman is an Egyptian poet, translator, two-time national literary award winner, animal lover, feminist, film critic, and philanthropist. She has published film criticism articles, short stories, poems, and translations in many websites and offline publications such as “Al Ahram”, “Vague Visages”, “Synchronized Chaos”, “theProse.com”, “Cinema Femme Magazine”, ” Eye on Cinema” and “Guardian Liberty Voice”. She Won the “Bleed on the Page” Competition for Poetry and Prose for her piece titled “Poof, Vagina”. Her first short story collection, “Thus Spoke La Loba”, was published in 2016 by the Egyptian Supreme Council of Culture. Her first poetry collection in English, “Work Station Blues”, was published by PoetsIN, a British publisher.

Looking forward to Part II: Day of the Soldado (?)