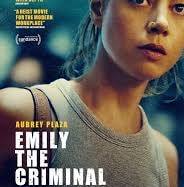

Why the world needs more unlikeable female heroes

Emily is no criminal.

She’s the male anti-hero viewers have been fed to love and pine throughout the pre #MeToo era. She’s not likable, doesn’t talk about her past or present, and does not try to save or be saved, and when the heat comes around the corner, she flees.

Emily is the Neil McCauley to viewers’ Lt. Hannah, and she knows how to play it cool even at the darkest times. Her violence seems impeccable but shaky contrary to badass women in movies. She’s relatable and could have been any woman who has found herself in a situation where only the fight vs. flight responses stir the wheel.

In John Patton Ford’s “Emily the Criminal,” poverty, classism, misogyny, and injustice take over the action-packed hour-and-a-half feature. In no way do these heavy topics seem squeezed or rhetoric as they stem from a solid narrative, authentic and faithful to the story about how someone’s life could complicate as the system disables them from finding a way to succeed without going astray. Like McCauley’s determination never to go back to prison, Emily’s determination to pay her loans and never face another day with her face down drives the narrative. Her reactive violence has made her into the modern-day hero that viewers can easily root for. She’s no otherworldly strong woman who eats men for breakfast. Emily is afraid, hurt, bent, threatened, and insulted. But the difference from the other women in action movies is that she fights back with no prior training required.

Emily uses the MacGuffins thrown her way or the ones she randomly finds. Emily challenges the modern workforce, toxic femininity in the workplace, and the hypocrisy of women in managerial positions. She demands equal treatment from female managers who supposedly have made it, denouncing younger women who have to scrap a living while reminding them of how their “struggles were harder” and their fight against patriarchal male-dominated workplace “acts of martyrdom”.

Aubrey Plaza’s deadpan, serious, expressionless, tired, and worn-out features relate to other female viewers. Her realistic-looking face and skin of a woman who does not have time for skincare or beautification immediately hooked me. It is not some Hollywood pampered celebrity wearing shabby clothes to look “poor”. She has the face of a woman who has tasted misery, fear, financial tightness, and a hectic lifestyle. The contrast between Emily and her friend Liz shows through both actresses’ looks and clothing styles. The dialogue reveals a lot without being blatant. It draws people in through attention to detail where they get glimpses into Emily’s endless work shifts and sleepless nights. The film’s social commentary is bold but never takes center stage, allowing the main protagonist to shine and let the commentary and criticism flow through her. Scenes shot from the back a la French films styles (think Xavier Dolan and the Dardenne brothers) take the viewer on a journey where doors slam shut, food trays are delivered, corridors are walked, and business is sealed. The multiple times Emily has been shot from the back add to her mystery and turn her into a complex riddle that viewers strive to solve.

One of the highlights of the film is Emily’s relationship with Youcef. The sexual tension between the two characters is highlighted beautifully and with elegance. The film portrays Youcef through a sympathetic, understanding lens. He seems like an Arab character seen through the French filmmaker’s lens, as opposed to how most Arabs appear in popular American movies. Youcef lacks Emily’s boldness and assuredness, but his layered, complex relationship with women shows through the scenes where he blames her or allows her to be bullied by his controlling relative. The tender and intimate relationship between an Arab son and his Mama are shown beautifully in one of the rare peaceful scenes in the film. Viewers mostly watch it through Emily’s unflinching -yet mesmerized gaze- as she follows around the warm relationship between mother and son, which may hint at her lack of a similar familial experience.

The film dismisses Emily’s artistic side. That adds to the film’s supremacy as it clearly shows how dire financial situations and low social status suffocate the art and cause some artists to give up, or throw their talent behind out of frustration or self-loathing. Emily is an artist at heart, but she hates herself for not being the artist she is meant to be, so she denies it anytime someone brings it up. This part hit home for me, as I have been a struggling poet throughout my life, and during many stages, I have had to give up on my art and compensate it for regular jobs which pay little and do not satisfy the artist’s hungry soul. These dark phases have turned my relationship with my craft a bit unstable but also erratic, and it has taken me a while to get back on track in terms of reaching an upward curve that could have been present if not for the year’s gaps and interruptions.

The Emilys of our modern time matter. Recently dark, comical, sexual, and dangerous female characters have emerged in film or TV, but characters like Emily Benetto need to be more seen and heard. Their simplicity and relatability will resonate with many women worldwide watching and feeling burdened by social, economic, or societal injustice. Emily may not be a hero, but that’s why she needs to exist in a fictional world that seems horrifyingly similar to ours. We need the Emilys that empower the average workaholic woman.

The modern, practical, workaholic woman doesn’t need to cater to patriarchy. She needs outlet and catharsis through Ti West’s “Pearl” or Jennifer Kaytin Robinson’s “Do Revenge”, “Emily the Criminal” is a milestone in having the George Clooney and Brad Pitt complex misunderstood but lovable characters. They are mean, snarky, sneaky, unreliable, and narcissistic, but that’s part of their charm. Emily is by no means the poster kid for the female workers’ alliance -leave that to Norma Rae (1979)- but she has been suffering and facing unrealistic expectations from future jobs she applies to. That leads to her refusing to take bullshit from anybody, not a lover, a coworker, and especially not from a dark-rimmed glasses female superior who lectures her on generational differences in taking down the patriarchy in the workplace.

A great review. I appreciate your ability to articulate your insight.