Them Changes (Quoth Buddy Miles)

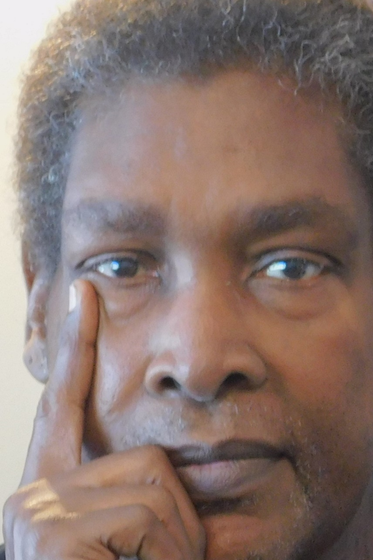

Doug Hawley

The History of Portland Oregon Seen Through Blurred Lenses

Pre Doug History up to 1943

Here are a few select happenings before me.

Visitors from the old world arrived from a temporary land bridge from a mythical land which was eventually named Siberia. They were good with boats and had good running through the inland passage formed by islands off what came to be Alaska (native for “really cold”) and British Columbia (named after a colonial power and a reviled guy that had nothing to do with Canada). Experts believe that they were drawn by the many outdoor stores and fly fishing.

European residents learned about what became known as the Specific North West by fur trappers and traders and the Lewis and Clark expedition. Portland got a big boost from the 1905 Lewis and Clark Exposition used to promote the city. Side note – the Largest Log Building In The World leftover from the Exposition was around long enough for me to tour it before it burned down. Despite Portland’s position at the confluence of two rivers – Columbia and Willamette – its ranking among West Coast cities has been sinking for some time. Seattle and San Francisco gained from gold rushes. Other places have better ports (getting to Portland via the Columbia requires going though the Graveyard of the Pacific), and attracted bigger business.

A few years ago, elderly friends told us they met at Lewis and Clark (meaning the college). I asked if they meant Expedition or Exposition. I hope that their laughter was sincere.

The next big deal for Portland was the shipbuilding during WWII, which leads up to my first turn here.

Doug’s First Portland run 1943 – 1965

Personal – Lived in Northeast Portland in a house built in 1941 which my parents moved into about the time that my sister was born. Went to what was Whitaker Grade School. It survived through a couple of fires and now houses Native American Youth And Family Center. Excruciating biographical information is in “Cities” in my blog.

I barely remember the 1948 Vanport Flood. Vanport was named for Vancouver WA and Portland. It was used to house ship builders during WWII. Whites and Blacks were recruited from all around the country. Oregon has a cruel history in racial relations – no need to recount here. Blacks were redlined into a small area and many had not gotten out when the flood came. Water came up close to the back of Whitaker and Vanport, once the second most populous city in Oregon, was destroyed.

In the late 1940s Portland was a crime and corruption hotspot. The book “Portland Confidential” gives the details. As a young kid, I remember seeing gambling devices out in the open, particularly punch boards. Dorothy McCollough Lee was elected a reform mayor in 1949. Portland didn’t care for reform and she wasn’t re-elected. She taught as a substitute in a political science class I took, but I remember nothing from it.

Throughout those years Portland was a Democrat and union stronghold in a mostly Republican State. It was conservative socially and culturally. Portland was known as the whitest city in America (no longer true I think). It changed some during those years, but racism and Anti-Semitic didn’t disappear. During my Portland State years, the times they were changing. Marijuana, which some thought was just a Black thing, moved into wide use and there was rebellion over Viet-Nam. Queer culture was emerging into prominence.

Like the rest of the country, the suburbs grew because of better schools and better houses. Urban Renewal (Negro removal), hospital and other major construction projects such as the Memorial Coliseum and freeways took away a lot of the housing. Ethnic enclaves were broken up. While Portland the city stayed relatively stable, the suburbs burgeoned and everything merged into a big slurb. Farm towns of ten thousand population grew as big as a hundred thousand.

There were no major league sports in town. There was a Triple A baseball team and college games. As a boy scout I ushered some pre-season NFL games played in Portland.

Portland was characterized as boring white suburbs, which is mostly correct. There was the Black community in North and Northeast Portland. A few Asians lived in Portland, but they were limited by the Japanese being sent to internment camps during WWII and the earlier Chinese Exclusion Act. The near west section of Burnside, which divided the town into north and south, had a version of skid road (if you want to be bored, ask a purist why it isn’t skid row). It had (and has) a mission and flophouses serving the down and out. Famous Tempest Storm was a fixture at the burlesque house.

The out of town years 1965 – 1997.

During those years I was in Eugene Oregon, Manhattan (Kansas that is), Atlanta, Louisville, Denver, Los Angeles and Marin CA. Got married, earned a living, switched occupations, became self-employed house husband.

Over time on trips back I noticed changes. What had been green bean and berry farms between Portland and Gresham were housing developments. The two cities had grown together and annexed the land that had been between them. My old home got swallowed by Portland.

Portland got an NBA franchise, the Trail Blazers, and won a title.

While visiting my mother a house cattycorner to her place burned down. The people who came out looked like representatives of the United Nations. Portland remains majority white, but not as much. The first shopping center in our neighborhood from the early 1950s became Hispanic oriented.

Doug’s Second Portland Run 1997 –

I came back to a place that was the same and yet different. I thought of it as a backwater compared to eighteen years in California, but Portland wasn’t much different than California and deemed to be an “it” city. Compared to major West Coast cities it is less expensive (we bought a condo for half of what we sold our place in California for, but later moved up to a better place than what we left at about the same cost). The comparison may still be valid now that home prices in both places have doubled or so. According to my last check on Zillow our old California place after apparent upgrades, on fill, in an earthquake zone, was valued at 1.3 million.

Some things here are much the same as the rest of the country.

Crime rates went down – but Portland now is setting highs in homicides..

Department stores are failing, particularly downtown ones. We visited the downtown icon Meier & Frank store shortly after returning to town. It was where people ate at the Georgian Room, met under the clock and children went to see Santa in a monorail. You could buy clothes, appliances and furnishings there. Clark Gable sold ties there many years ago. After going through changes, the building is the luxury Nines Hotel. Of two major local stores of my youth J.K. Gill closed shortly after I returned and Olds and King closed before.

Traffic congestion increases. When I moved back I could drive thirteen miles west side to east side to see my mother in eighteen minutes. We laughed at people who talked about traffic here. It was nothing compared to Seattle or California cities. We aren’t laughing anymore.

Beer is something in Portland’s favor. We discovered the McMenamins lodging, restaurants, resorts and drinking empire. When we are at one of their places, we get Terminator Stout, at other places we get Black Butte Porter from Deschutes Brewery in Bend or a different dark. Portland has competition for Beervana, but it is in the running.

Portland lost baseball and got soccer. For some that is a gain.

We don’t go into Portland much (we are eight miles south of downtown), but we do enjoy the zoo, art museum and the museum of science and industry. The zoo is the most changed, it moved and became much bigger and better. Its main claim to fame is the elephants that recently got a bigger habitat. The museum of science and industry also moved.

The best part of Portland is the access to adjacent Oregon and Washington. The Columbia Gorge and Mt. Hood to the east and the coast to the west are beautiful with hiking, skiing and snow shoeing trails for hundreds of miles. They are available on days without flooding, freezing or burning.

Portland itself is well known for rioting, protesting, crime and thousands of people camping all over the town. Every election someone promises fixes, but nothing changes. The qualification for mayor is to be ideologically correct. That includes, but is not limited to, punishing business and rich people. The Portland council form of government means that people who have the ability to convince people to vote for them get appointed to positions which should require intelligence and professional qualifications as the heads of various bureaus. It is stupid and it shows. As in the rest of Oregon, hiring bad employees and then paying them to go away for fear of being sued is standard practice. Bad cops go to mediation and get little or no penalty, one of the downsides to fealty to public unions. The retirement plan for police and firemen is pay as you, a poor financial practice, particularly given the ease of going on disability and early retirement.

Politics hasn’t ruined the weather in Portland; climate change took care of that. Then – moderate rainfall, temperate summers and winters. In the last year or so, we went 5.5 days without electricity and the neighborhood was scattered with downed trees and branches because of an ice storm, had a heat dome that raised the temperature to 115F where nothing over 107F had previously been recorded, and wind blew one of our fences down. The forest fires give us a lot of toxic air.

On top of Oregon’s 9% income tax rate, Portland adds 1.5 – 3% for “high” earners, and “high” isn’t very high – a good reason to go across the Columbia to Vancouver Washington with no income tax if you make very much money.

With all of the bad, why has Portland attained its exalted status?

Exaggerated woke/progressive image, as opposed to the incompetent, second rate reality.

Cheaper than the other guys, but still expensive.

Things are bad everywhere.

Laid back presentation by the “Portlandia” series.

The country around Portland.

I hope that this discourages anyone from moving here. There are 2.5 million people in the metro area now, up from the much more manageable and pleasant under a million in my youth.

Much of the above is true.