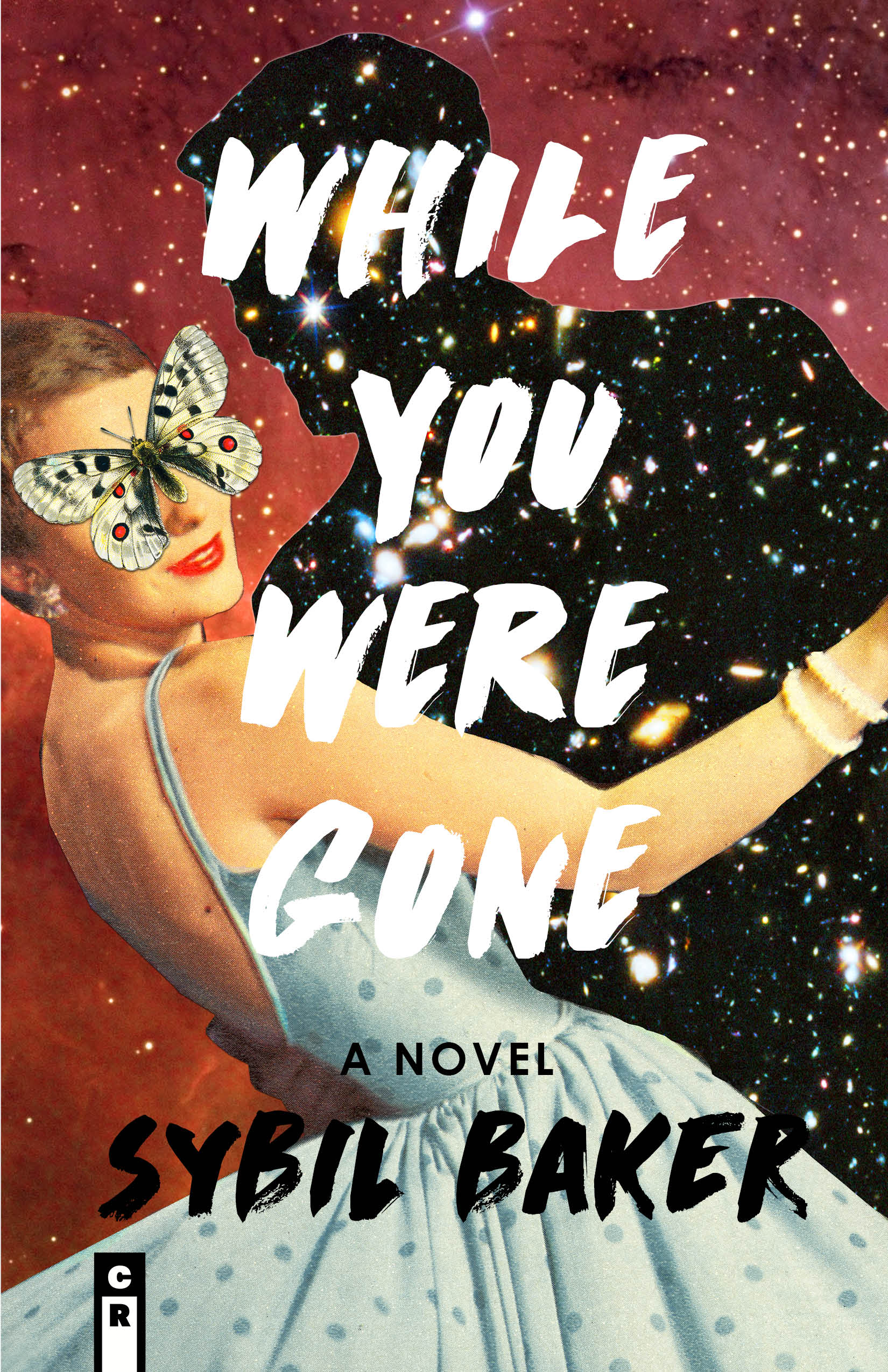

Book reviewed in Chapter 16 Magazine

Jeremy’s Car 1995

Because it’s not too far to the Walnut Street Bridge, Shannon’s cousin and prom date Jeremy insists on driving with the top down. Even though it’s chilly for early May, Shannon doesn’t stop him, nor does the girl sitting behind her in Jeremy’s Mustang convertible.

Julie, her name is. David’s date. Of course Shannon knows. Julie’s one of the popular girls, pretty in a way that is not extraordi- nary, because who in high school wants to be extraordinary? Julie’s beauty, the thick shell of hair she’ll cut after she marries ten years from now, the long gangly legs that will eventually thicken and soft- en, the pale dewy face that will also succumb to early wrinkles, is at its peak, but Julie, Shannon thinks, at least has this. Shannon is not a beauty nor will she ever be one, especially on this night, with the red chicken pox spots and scabs dotting her body as if she were some crazed pointillist painting. She’ll not be even almost-pretty the way her older sister Claire is, her features uniformly bland and non- confrontational, nor will she be striking, the way her younger sister Paige will be someday, though for now she just looks strange with her broad face and wide cheekbones. Shannon knows she will have to rely on other things, boring things like perseverance and commit- ment and ambition to get ahead, to maybe find love. But for now, there is no love, no success; there is just getting through one of these

final, awful moments that is high school so she can start life over as the new, improved Shannon when she begins college in the fall.

She’d not even wanted to go to the senior prom, but Jeremy had talked her into it, said he’d make all of her friends jealous, and be- sides he’d always wanted to go to a public school dance. Like being in a John Hughes movie, he said. He was darkly handsome, from one of the old Chattanooga families, and attended the city’s most prestigious boys’ school. A veritable Prince Charming, except for the being gay part, which most people didn’t know about. She believed him when he told her he was doing this for her out of kindness and not pity, as her cousin and best friend for as far back as she can remember. He’s her cousin on her mother’s side, the side with inheritances and trust funds. The side that started forgetting her and her sisters after Jeremy’s father had died thirteen years ago and their mother, his sister, had followed three years later. Now Shannon’s father works a nice white-collar job as an engineer, and she is graduating from a magnet public school and going to college, but this is not enough for Shannon, who envies Jeremy’s world, envies what she might have had.

Because he means well, she’s agreed to let him take her to the prom, but then she’d contracted chicken pox and even though she would no longer be contagious, she refused to go. Her face was puffy, her skin mottled and angry looking. She would not endure the humiliation. But Jeremy would not have it and showed up one afternoon with a dress that she would have never bought for herself, even if she could have afforded it, even if her mother had been alive to choose one with her. He was stereotypically gay in that sense, with a flair for fashion she didn’t have or care about. The dress was a sleek violet Thai silk, and there was nothing public school about it. She tried the dress on for him, her face and arms covered in red bumps, her skin tender as a bruised plum.

“You’ve lost a few pounds,” Jeremy had said.

“The chicken pox diet.” The dress had a mandarin collar and capped sleeves, covering much of her pocked and swollen skin. “This is not me.”

“It is now,” Jeremy said. “I’ll pick you up at seven.”

He’d arrived in his new convertible, the first time Shannon had seen it, a slightly early graduation present (a thank-God-he-graduat- ed-and-made-it-into-college present, he said), as darkly handsome as he always was, but more so in the suit, Brooks Brothers, for although he had an eye for women’s fashion, his own sartorial choices tended toward his family’s traditional Southern prep. Her corsage was an or- chid, an expensive but scentless variety that would look diminished instead of elegant next to the other girls’ outsized corsages smelling of honey and violets. He took her to a fancy restaurant overlooking the river, where they ate flesh from exotic animals and shared a bot- tle of wine, even though they were both underage, a feat only Jeremy could get away with. Her face, barely camouflaged under layers of thick foundation, flamed like a recently struck match. Shannon, who felt like a red popsicle on a purple stick, reminded herself this too would pass.

She self-righteously suffered through the humiliation of the

prom with a modicum of grace, for she knew that soon she’d be away from all this, at college, becoming a journalist, never looking back. And Jeremy, well, was Jeremy. Charming and smart and good-look- ing, from the right family, from the right school. Except for the gay thing, he was an ideal Southern boy. He was doing what he thought was a favor for Shannon, who had on more than one occasion suf- fered through his own school’s dances because he didn’t want to bring a date who might want more from him. Suffered his friends’ date’s appraisals that found her lacking, the slight head shakes, eyes wide with surprise: you’re with him? Suffered the questions in the bathroom as she tried to revive her wilted corsage in a spotted sink. Why is he taking you? Why won’t he take a real girl out? What’s he hiding? And now here she was suffering again, where she was sure the girls were just like the ones at Jeremy’s dances, thinking the same things. Why would he think her classmates would envy her, when they knew that he was, after all, her cousin and she was the pity date?

But now, as Jeremy idles the car in front of the bridge, ignor- ing the blasts of cars passing around them, she catches him look-ing in the rearview mirror. David, with his sun-streaked shaggy hair touching his collarbone, sinewed skinniness, doe-like eyes, tie- and coat-less, barefoot, smoking endlessly into the night: Jeremy’s type. She punches Jeremy hard in the arm, angry more at herself than him for being so slow on the uptake. The real reason he wanted to go to her prom is now smoking in his car. He smiles more than grimaces, winks as he rubs where she punched him.

“You can’t stop here in the middle of the road,” Julie says. “You’ll get a DUI.”

“I’m idling,” Jeremy says. “Because I want y’all to appreciate our lovely pedestrian bridge, saved from dissipation and destruction, thanks to the efforts of Chattanooga’s citizens. Our pride and joy. ’Course y’all know this bridge is not just famous, but notorious.”

“The lynching of Ed Johnson,” David says. “I read Shannon’s piece about it in our paper.”

“You and Dad were the only ones,” Shannon says. But she smiles. Her face cracks from what’s left of her caked-on makeup.

“I don’t remember any lynching,” Julie says.

Jeremy gestures for one of David’s cigarettes, and he passes his lit one to the front seat. “It was in 1906.”

“Oh. Doesn’t really count then.”

“Well, it kind of does,” Shannon says. “Ed Johnson’s lynching resulted in the only Supreme Court criminal trial in history. Not that his was the only lynching on the bridge.”

“Blah blah school blah,” Julie says. “So that’s why the river smells so foul.”

“That and all the chemicals dumped in it. Remember, we were once the most polluted city in America.”

“But not anymore. Why dwell on the past?” Julie reaches into David’s jacket pocket and pulls out a flask. She unscrews the top, takes a swig, and then passes it to David. “Let’s have some fun.”

“You know who the ringleader of that mob that lynched poor old Ed Johnson was?” Jeremy asks. “My great-great-great-grandfa- ther on my mother’s side. That’s who. A black man falsely accused of raping a white woman, and they shot him and hung him.”

“You related to this guy too, Shannon?” Julie says.

In the rearview mirror, Shannon watches Julie scoot closer to David. Shannon’s convinced: Julie thinks she’s winning now, that she’s putting Shannon in her place by reminding everyone that Jer- emy’s her cousin. She actually believes, Shannon thinks, that she’ll have sex with David later. She wants to tell her to give up now, but she knows Julie won’t listen. “It’s the South. We’re all related one way or another, aren’t we?” Shannon says.

Jeremy laughs, and a few seconds later, David joins in. A siren wails, coming closer.

“Let’s go,” Julie says. “Not yet.”

Shannon closes her eyes, flutters her hands over her face. Her skin feels hot and bare, tender, the makeup smeared and sweated off. She hears Jeremy’s door open, the shift in his seat. She reaches out to touch his thigh, to stop him, even though it’s futile, even though he’s gone. She hears Julie’s voice, anxious, terrified. Shannon could tell her not to worry, that the emergency brake is on, they are safe for now, but doesn’t. She opens her eyes, watches Jeremy at the rails of the bridge, climbing them. It’s a pale darkness, one grainy from the diffused light of late sunset. The mornings are dark here almost year- round, but those nights in summer, it’s like the sun will never set.

He’s on the rails now, screaming like a god or condemned man; it’s hard to tell. Below, the water sparkles; above, the sky ab- sorbs the light. He’s done this before, drunk and sober, and she’s always there to pull him back, talk him down from jumping. Just as she’s held him, wracked and sobbing, smoothed his curly hair, her steady voice convincing him that even in the most painful moments of being Jeremy Hamilton, it is still worthwhile being alive.

But this show is not for her. David gets out of the car, jogs down the middle of the bridge. She watches him gesture to Jeremy. He takes a small camera from his jacket pocket. Jeremy laughs, poses for David, arm and leg stretched toward sky and water. She knows Jer- emy is smiling for David, who holds his hand out, helps Jeremy down.

“He’s crazy,” Julie says. “Maybe.”

“We got a room at the Read House,” Julie says. “They say it’s haunted.”

“Well, a woman’s head was severed there. And Civil War sol- diers were murdered. And there were the suicides. Just because that stuff happened doesn’t mean it’s haunted more than anyplace else.” “I don’t want to think about it,” Julie says. She leans toward Shannon, cupping her hands over her mouth as if they are in a crowd-

ed room. “Momma thinks I’m spending the night at Abbie’s house.”

Shannon pantomimes locking her mouth, tossing the key out the window.

The boys are back in the car, breathless, slightly sweaty from the excitement. Jeremy releases the brake and shifts the car into gear. “One more place, then I’ll let you two get back to the night

of your lives.”

David snorts as Jeremy turns and drives up Third Street, to- ward the worn-down neighborhoods at the foot of Missionary Ridge. With each block, the houses become tinier and neater, as if darkened curtains and well-kept gardens strain to maintain order against the neighborhood’s slide into ruin. The air, heavy with wild honeysuck- les and uncollected trash, rushes past them.

“Can you put the top up?” Julie whispers. “I’m scared.” She leans into David.

“We’re all right,” Jeremy says slowly. “For now.” A smile creeps up his face.

He parks the car in a gravel space overlooking an overgrown cemetery. “This is where we buried the black people, ’cause we didn’t want them next to us even in death.” By now the darkness has seeped into the sky, the ground, the air around them. Jeremy and Shannon get out of the car, and David opens his door. Julie whim- pers and then steps out, last. They walk past the worn grave markers, many still unidentified, through the ghosts they can all feel, up and down faded paths to the gravesite of Ed Johnson. Jeremy sits next

to the headstone and pats the ground for the others to join him. The moon is half full, the stars dimmed by the city lights. Shannon can feel Julie’s shoulders shaking. David drapes an arm around her, and her body stills. The flask of whisky is ceremoniously passed around. Shannon takes the smallest of sips. Jeremy whispers the words on the gravestone, but loud enough that they all can hear.

“God Bless You All. I Am An Innocent Man.” Jeremy’s voice breaks at the end. He touches the top of the grave. “On behalf of my country, my family, I’m sorry, Ed.”

The thing is, even though she’s seen him do this before, this routine, this ploy, Shannon knows he’s not exactly faking either. Jer- emy rises and disappears into the woods.

“Is he coming back?” Julie asks.

“He’ll be okay.” Shannon waits for David to stand. Finally he does. “I better go check on him. Y’all go on back to the car,” he

says. Then he too disappears into the dark.

Back in the car, the two are silent for a long time. Finally Julie speaks. “I don’t know why Jeremy’s so upset about something he didn’t do.”

“You ever read Faulkner?” Shannon says. “Why?”

Shannon closes her eyes. Nothing lasts forever, she reminds her- self, and then the other voice, her little girl voice, adds: except death.

“I just want him to take us to our hotel,” Julie finally says. “He will.”

“He seems a little crazy.” “Just emotional.”

“David’s going to Virginia Tech. ROTC.” “So I heard.”

“Real marriage material.” Julie snaps open her clutch, removes a compact, dusts her face even though it’s too dark for anyone to see her. Shannon thinks of her own mother, and the other dead people lying in the ground around them. “What about Jeremy?” Julie says. “He’s going to Sewanee, right? You’re not hooking up with him?”

“Jeremy? God, no.”

“I mean y’all are cousins and all, but,” she giggles, “it is the South. Ha ha.”

“Not going to happen. Ever.”

“It’s the first time for me and David. That’s why I want to get out of here. He’s so hot.”

“Mmhm.” Right now, she guesses, David and Jeremy are making out, fumbling under shirts, tugging pants down. Perhaps a blowjob—or two—is in the equation. “Jeremy’s not my type.”

“Who is your type?” “My type is John Reed.”

“He go to school around here?” “He died in 1920 of typhus.”

“Oh.” Julie plucks the pins out of her hair one by one, leaving them on the seat beside her. “That’s creepy.” Hair clumps shoot wildly in all kinds of directions. She runs her hands over the sections, finger combs through the hairspray. “That’s pretty brave for you to go to prom with your face like that. I could never do that.”

“Don’t worry,” Shannon says. “It’s not contagious.” Just a while longer. Soon Jeremy will be back and she can go home and she will graduate and leave the Julies of Chattanooga behind. She lays the back of her hand on her forehead, bumpy like a rough road of gravel. She imagines herself witnessing revolutions and writing about them, accepting the Pulitzer Prize.

Then she hears their voices, low and conspiratorial, approaching. Even though her eyes are still closed, Shannon knows Jeremy’s shirt is untucked, the tails of white fabric almost glowing under his suit coat.

“The good thing is,” she can hear Jeremy say as he gets into the car, “I’ll never be as bad as my great-great-great-grandfather, no matter what my mother says.”

Shannon opens her eyes, watches David slide into the back and Julie wrap her arms around him. “Everything okay?”

“Dandy,” David says. “You two want to stop by our room for a drink?”

“No, thanks.” Shannon hates that she’s taken Julie’s side on this one. If she had the energy, if she cared enough, she and Jeremy would go with them to the hotel room, and Julie would never get what she wants.

“David,” Julie says, dragging his name out. “I have to pee.” “Can’t it wait?” David sinks a bit in the seat.

“I’ve been holding it for-ev-er.” She opens the door, swings her legs out. “Just walk with me down the hill. I’m not walking by myself. I might get raped or knifed or something.”

“Go on, Davey,” Jeremy says, waving his hand. “We won’t leave you.”

After the two disappear, Jeremy reclines his seat, massages his forehead. “So, I got some news.”

“You moving to New York?”

“Not without you.” This is their plan. Right after college. He takes a breath. “The big news is I told Mother I’m gay.”

Shannon sits up, turns so she faces him. Since her mother died ten years ago, Shannon has avoided talking about the things that hurt. She touches his shoulder, thin and bony even under the suit coat. “When?”

“Last week. After I got the car, of course.” His hands trace the steering wheel, in smooth, even circles. “You know what she said?”

Shannon is afraid to fill in the blank. None of the answers are good ones.

“That I was adopted.” “She’s lying.”

He turns to her, scrunches his face. “Did you know about it?” Shannon shakes her head. “You know I didn’t.”

“She said I must have inherited being gay from my biological parents, so it’s not her fault. I told her I’d rather have the gay gene than the lynch mob KKK gene.”

“Hah,” Shannon says. “Sure that went over well.”

“She said she can just as easily leave her money to some charity.” “She’ll get over it.” But they both know she won’t. Shannon

wants to say more, to comfort him properly, but her throat feels clotted. Closed. She reaches for him and he folds into her as he’s done before. Ever since she can remember she’s been terrified of losing Jeremy, to love or despair or both. “I’m sorry,” she says.

“Break it up, you two.”

Jeremy pulls away. She’s glad he hasn’t been crying; at least he’s spared that. And she’s grateful now for David, barefoot and rumpled, his hand momentarily on Jeremy’s shoulder as he climbs in. After everyone’s in the car, the wheels crunch out of the park-

ing spot and they’re back on Third Street again. At the stoplight on Third and Market, Julie taps Jeremy’s shoulder. “Shannon says you’re not her type.”

“Don’t worry, Jules. Me and Shannon are still kissing cous- ins.” Jeremy pulls Shannon close to him so suddenly she doesn’t resist and kisses her hard on the mouth, a flick of tongue even.

“Oh my God, she’s diseased.”

Jeremy laughs, but it sounds more like a bark than a human laugh.

Shannon turns around and sticks her balloon-face over the seat. “It’s not contagious.” She rakes her nails over the fading pox bumps. She’s been good about not scratching, not leaving scars, but this is worth it. She rubs her hand on Julie’s exposed thigh.

“You freak.”

“You know what, Julie? Me and you, we’re going to remember this day for the rest of our lives. For you, it’s because you went to the prom with big man David here and, if he can get it up for you, you get to fuck him. It’s going to be the best day of your life—after this it’s a boring husband or two and screaming children and a dead-end job and bad haircuts for you.” Shannon turns and faces the front as the light turns green. “But for me, this is the last day of life sucking. It only gets better from here.”

“You wish, loser bitch.”

“Shannon’s right,” Jeremy says, pulling up in front of the ho- tel. “In the words of Ol’ Blue Eyes himself, the best is yet to come.” The car idles. He reaches his hand back to David, pats his knee. “Go on. I won’t miss you.”

After David and Julie disappear into the lobby of the hotel downtown, Jeremy leans back in his seat and closes his eyes. “You got a present for your dad’s birthday?”

Shannon hits the dashboard with her hand. “Shit, I forgot.” “The party’s not till dinner, right? We’ve still got time. I’ll pick

you up for lunch and we can go shopping then.”

Shannon reaches over and squeezes his hand. “I swear I didn’t know you were adopted,” she says.

“I know.” He opens his eyes, pulls the top up so that it blocks the night stars, shifts into gear. “God, will I ever love anyone as much as him?”

Soon, Shannon thinks, soon she’ll be happy. She can feel it. “If we only knew, Jeremy. If we only knew.”