With the Other Foot

by

Fernando Sorrentino

Translated from the Spanish by Howard Jackson <jacksonhoward09@googlemail.com>

Spanish title: “Con la de palo”

1

Dr. Arturo Frondizi and I were both tall and skinny. At the time, he was starting his second year as president of the Argentine nation. I was a senior in the school located on the El Salvador and Humboldt Streets in the city of Buenos Aires.

More than once, through the strange workings of the human mind, I had the following thought, ‘I know the existence of Frondizi, but he doesn’t know mine.’

The district the school was in was also my district, so I was quite familiar with it.

Near the end of Costa Rica Street, I mean just a few yards before you get to Dorrego, there was a car repair shop. I used to see the mechanic that worked there standing outside the shop on the sidewalk. Sometimes, I saw him lying down under a car. He was always wearing grease-stained blue overalls. Whatever he was wearing, you couldn’t fail to notice him. He was over six feet tall, and, judging from his husky build, he must have weighed over 250 pounds. He had a ruddy round face with light blue eyes and blond hair, so blond that it was almost white. He must have been about thirty years old.

Costa Rica Street, where it crosses Dorrego and turns into Cramer, puts you in the Colegiales neighbourhood. In another hundred yards or so, back then, there was an enormous empty lot called the Campito (Little Field), which crossed Álvarez Thomas and Zapata Streets and went lengthwise down as far as Jorge Newbery Street. The Campito had room for several soccer pitches. These were the setting for the informal games that took place between teams made up of local amateur soccer players. There wasn’t a single blade of grass on this huge lot, just hard dry dirt.

To get to the Campito it was necessary to cross a depression. Every now and then, and at the bottom of the slope, a freight train used to make a single round trip on the line which connected the Mitre Colegiales and San Martín Chacarita stations. The train has not operated for a little more than a half century. Today there is not the slightest threat of danger from passing trains. But back then, when the only train with a black steam engine on that line blew its long, sharp, sad whistle, crossing the track was a little creepy. All locomotives in those days, just like boats, had a name. This one, written in white letters, was the GAUCHITA.

2

So, on one Sunday morning in July, I went down a 45° slope onto the railroad track. I heard no whistles, but, just in case, I looked right and left and crossed the track before starting up the other slope. I was going to join my friends on a team called the Rayo Azul (Blue Flash). We were going to play a ‘friendly’ game against an unknown team from a nearby area called Amanecer de Bollini (Bollini’s Dawn).

These games were managed by a man named Azzimonti, I never knew his first name. He was a gruff chap that always had a cigarette hanging from his mouth. When he was young, according to what he told us more than once, he had played on a second-level team as an inside forward. That qualified him to work with us as a sort of a coach. He had an assistant they called Tijerita (Little Scissors), I suppose because he had once been a barber.

There were no dressing rooms or anything like that. On the touchlines before the game, we put on our football kit, and after the game, we put our street clothes back on. About 300 yards away on the edges of the slope, there was a tap, about three feet high and with running water. There, if we bent over or crouched, we could cool off, take a drink, wash up a little, although most of us, exhausted after the game, were too lazy to travel such a distance. We preferred to head home, thirsty and sweaty.

Azzimonti, once again, had picked me to play, and I, not displeased with myself, agreed. The position of left winger had not been resolved. Sometimes, I played on the first team there, Hugo Martínez was the sub, and sometimes vice versa. This time, however, I started the game in that position.

To tell the truth, my soccer skills were not too great.

But I was good at dribbling, my shooting was precise and powerful, and I was very fast. In fact, they called me ‘The Greyhound’. If I was right-footed, I could still shoot with my left foot, my ‘weaker foot’, the ‘swinger’. But only while the ball was in motion. My left-footed shot, I don’t know why, was harder than my right-footed shot, but, unfortunately, it was not as accurate.

I had no other good moves. I was incapable of dribbling very far unless I had wide open space. And, to make things worse, in spite of my height I was a poor header of the ball. I could only connect to the ball with the left side of my head. Despite being right-footed, playing on the left wing was more of an advantage than a disadvantage. If I ran down the left side of the field, my shot with the left foot was weak. On the other hand, my right-footed shot could beat a full back that was used to facing left-footed forwards.

I was skinny, not very strong, long-legged, and barely weighed 130 pounds. You could count my ribs. My speed and ability to accelerate made me appear even more fragile and tempted the defending full back to send me flying. For my age, I was not fully developed. Most of my teammates and most of the opponents were husky men in their 20’s, some were even older.

3

The players of Amanecer de Bollini wore jerseys with red-and-blue vertical stripes and white shorts and blue socks. To tell the truth, our jerseys were a little naff. A brilliant blue stripe reached from the left shoulder to the end of the last rib on the right side. On the white background, the stripe appeared to vibrate electronically. We wore white shorts and blue socks.

The referee called us to start the game. We lined up and faced the ball, each one of our players took his position on the pitch.

I wore number eleven. On the other side of the halfway line, and wearing number four on his jersey, was the guy I had seen around. This big bloke with a ruddy face was none other than the owner of the repair shop on Costa Rica Street. I heard his teammates call out Tadeo, his name.

And just as happened to me before with Arturo Frondizi, I had the same absurd thought, ‘I know who he is, but he has no idea who I am’

The game started.

For the first few minutes of play, Amanecer de Bollini marked us so tight we were unable to get the ball out of our half or even clear our penalty area. You could say, I was not much more than a spectator. I hardly featured in the game. On the rare occasions I was involved in a couple of one-twos with a teammate, I struggled to control the ball.

We must have been twenty minutes or so into the game. It was a miracle that the game had remained scoreless. On another day, we would have been at least three goals behind.

In the midst of the constant attacks from this red and blue ‘army’, our left full back, usually not very noticeable but as close to his man as a blanket, kicked the ball sky high.

As the ball started to fall from the sky, I watched it drop down above me. Hardly moving, I managed to reach the ball with my chest. Because I am not that fast, the ball bounced off my chest and landed two yards away from me. I moved and trapped the ball with my right foot.

All this lasted about a second. Now, just a few feet from me was the gigantic figure of Tadeo, his legs spread wide, his arms spread out, and his blue eyes fixed on my feet.

I swerved a little and feinted that I was going to move inside to pass his left side. Tadeo fell for my dummy and he jumped to where there was neither me nor the ball.

This all took a split second, and, while it happened and Tadeo was running back to his own goal, he tripped.

That was more than enough time for me, the ‘Greyhound’ and my legs.

I controlled the ball with the inside of my right foot. I ran right past their number four.

The ‘Greyhound’ was now in enemy territory. With so much open field ahead, there was no point in keeping the ball under close control. I kicked the ball long and ran after it and towards the goal at top speed. In those few seconds, Tadeo had fallen behind me by a couple of yards, and I was now able to take a shot at the goal.

Their number two, running diagonally across the field, arrived at my side in the middle of the pitch but he had run too fast across the pitch and his efforts had left him disorientated and out of control. It was simple for the ‘Greyhound’ to use his foot without the ball, feint from right to left and trick such a clumsy ox. But the ‘Greyhound’ was almost standing on the goal line and he could not shoot. The only thing he could do would be to kick the ball with his left foot and hope that Lady Luck would do the rest. So, he kicked hard with his left foot, and not very accurately. Anything could happen now.

Lady Luck determined that among the four or five players in the penalty area, the ball would reach the right foot of the Blue Flash’s centre forward, who, unmarked, scored the first goal of the game.

4

We now lined up to resume the game.

I felt almost too happy. I was pleased with myself because of how well I had played and how I had helped my team to score first. This goal, although I did not score it, was made possible because of my physical ability and quick thinking.

This self-congratulatory state of mind caused me to make two errors. The first was mental and actually pretty slight. I had underestimated my opponent and had assumed he must be a terrible footballer and there for the taking. It was so easy for me to get by him and into the opponent’s half that I was sure he was going to get frustrated and that he would stay angry until the end of the game.

And that is when I made my second mistake, not at all trivial, but serious, catastrophic, in fact.

When Tadeo and I glanced at each other, I could not resist the temptation to form a circle with my right index finger and thumb. I held it up to my forehead, winking and smacking my lips in the famous ‘Look at me’ pose used by the comic actor Carlos Balá.

Tadeo did not think this was funny at all. He glared at me with a murderous look in those beautiful blue eyes, and he cursed me, and, because I could read his lips, I understood his insult.

The game continued and began to unfold in the same way as before. Once again, our defense was bunched up in the penalty area, and once again our goalie was stumbling and fumbling.

The ball came to me just like it had when the goal had been scored. With the hint of a gratuitous smile, I faced Tadeo and successfully repeated the same play, the one where I feinted to go inside but instead went on the outside.

But this time, I did not get four or five yards ahead of Tadeo. He didn’t fall for it, and I couldn’t gain an inch on him, let alone four or five yards. Tadeo, turning around with surprising speed, lurched in front of me with his right leg and then kicked me square in the shin. His violent attack left me unable to run or even move, and I fell flat on my face. My nose, chest, elbows, knees and legs all scraped against a hard, rough playing field that was especially unforgiving because of winter and the July cold. As I was falling, I tried to stop myself so that I could stand up and kick Tadeo in the stomach or anywhere I could.

But I couldn’t get to my feet. I was bleeding, in pain and covered with dirt. The referee called a foul against Tadeo, and my teammates jumped all over Tadeo, shouting at the full back for having made such a dirty play. A fight broke out. There was pushing and shoving, shouting and cursing.

The referee warned Tadeo but he did nothing else.

My nose, elbows and knees were bleeding profusely. I left the field to catch my breath. I was full of hatred and muttered, ‘Son of a bitch’. Still thinking of Tadeo, I said, ‘I’d like to kick him in the head and send him straight to the hospital.’

‘Take it easy, boy, take it easy,’ Azzimonti warned me. ‘Don’t lose it! That’ll just make things worse. Stay cool! Take it easy, control yourself!’

I went back out on the field. My clothes, just rubbing against me, hurt. I tried to cool down, but I didn’t feel at all like I did after we had scored. I now felt like a coward.

I realised that Tadeo had changed his tactics. He marked me so close that I was unable to receive the ball. ‘If they’ll just give me a yard, that’s all I need to control the ball. Then I’ll have some fun, playing against this big lug will be a piece of cake.’

Yes, definitely, but the fact is that that big lug didn’t retreat. I made sure I didn’t have that extra yard. He not only denied me the extra yard, he made sure I didn’t have half a yard or even six inches. He gave me nothing at all. He stuck to me like glue and each time he beat me to the ball. I could see his advantage, and it pissed me off.

I could also see his shortcomings, and that made me indignant. I was affronted. Tadeo was a dirty and crude footballer and totally without skill. In spite of his physical limitations, he made his headers, he shot with his instep, with his knee, with his shin. He may have gasped for breath but he kept trying. He was willing to sacrifice himself for the good of the team.

I was technically far superior to Tadeo, but I couldn’t achieve anything playing against this man mountain. As well as keeping me out of the game, all the time he was pulling my hair and giving me sly kicks that he hid from the referee. He slapped me on the back and banged my head. He pinched me, pulled my hair and spat at me. He continually shouted and swore at me, his voice broken by his heavy breathing, ‘You dirty son of a bitch, you’ll learn not to screw around with me. Asshole, I’m going to kick the shit out of you. You think you can dribble past me and look down your nose, you stupid bastard!’

That’s what Tadeo was saying to me, and he not only said it, but, while he was saying it, he was kneeing me and punching me and spitting on me. I had to feel his iron knees and steel knuckles and his disgusting spittle. Naturally I had no intention of being the victim. I defended myself and I attacked him. But I was not as strong as Tadeo. I could still feel the pain from his previous blows and fouls.

The first half ended. But far from it providing me with a welcome respite, I had to suffer as well the admonishments of a disappointed Azzimonti. He was furious at the way I had played. He was not interested in that I was playing against guys that were bigger than me.

‘Get on the ball, kid. Get hold of the ball, at least once. You have to shake that blonde guy off. He put you in his pocket.’

I attempted to explain to Azzimonti that whatever I did to try and leave myself unmarked and free, the blond son of a bitch, who couldn’t care less about what happened in the game, would follow me round the pitch. All Tadeo wanted to do was insult ME and spit on ME. He was not interested in winning the game.

Azzimonti shouted, ‘You have to have character, kid. If you are going to be intimidated and you don’t have character and a strong mentality, you’ll never play football.’

This was correct advice, of course, but when you are scared, there’s really nothing you can do. I felt like telling Azzimonti to put Hugo Martínez in for me in the second half. But I kept my mouth shut because that would have really made him angry. Nothing infuriated Azzimonti more than a player who wasn’t hurt asking to be substituted. He would consider that unspeakable cowardice and he would be right.

I was intimidated by all this and wanted to be anywhere else at that moment. But I went back onto the field, and the very same thing happened in the second half as had in the first. Tadeo continued to harass me. So much so that I had to agree with Azzimonti. I had no stomach for playing soccer anymore.

Fortunately, Azzimonti decided to change the team. With twenty-five minutes left until the game ended, Azzimonti put Hugo Martínez on in my place. During the second half, Amanecer de Bollini scored three goals. On the touch line, I had to suffer the torment of all those insults that Azzimonti and Tijerita threw at me.

I was humiliated, both by the tyranny of Tadeo intimidating and abusing me and by the recriminations of the head coach and his assistant. At the same time, I was angry with myself and ashamed of my cowardice. Sooner or later, I would be morally obliged to wreak vengeance on Tadeo.

5

After a while, all the players began drifting off the field. Dejected, I stayed sitting on the sideline until everyone else had disappeared. I was now dressed in my street clothes and had on my regular leather shoes. My athletic clothes were in my bag.

Finally, I stood up. Intending to cool off, I headed for the water tap that some of us used after our matches. This was right at the top of the hill leading down to the railroad bed.

Then, oh oh.

I saw the huge figure of Tadeo. He was crouched, and his head was under the water tap that was perched on the narrow three foot high cement column. He had his back to me and was splashing his head and drinking water.

I ran towards Tadeo. My intention was to kick him with my right foot, and land a blow on his back that would cause his face to hit the cement stand below the water tap. I would then run away at top speed. It was not without good reason that they called me the ‘Greyhound.’ Tadeo would never catch me.

But the second before I kicked him, Tadeo heard something and turned his blond head toward me. His ruddy face had an ironic and insulting smirk. His head was close to the water tap, so his blond head became my soccer ball. The ‘ball’ was in motion, and it was very easy for me to kick his head hard and violently with my left foot, ’the swinger’. Tadeo, lurched forward, spun and stumbled towards the railway tracks.

His body rolled over three or four times and landed deep in the dip between the two short but steep slopes that were either side of the railway track. I heard the loud crack that his skull made when it hit one of the hard railway sleepers. And there he was, lying flat across the gravel and the rails.

He was not dead. I could see him move albeit somewhat spasmodically. Now, I was transformed and once again the ‘Greyhound’. I raced across the top of the slope that edged and looked down on the railway track. I had to get away from the railway track as fast as I could and to be far away from the injured Tadeo. I did not want to see him suffering.

A hundred yards, three hundred and five hundred..

And then I heard, and not too far away, the long and sad whistle of the approaching engine—the GAUCHITA.

6

That day was the very last day I ever played soccer, but not really because of my cowardice, a weakness that Azzimonti had pointed out to me.

I just never wanted to see myself in that situation, kicking with my ‘weaker’ foot, that is, my left foot. I could kick hard with this foot, but not accurately. And when the shot isn’t accurate, well, anything can happen

And, because I was haunted by two fears, I never walked by that end block on Costa Rica Street.

On the one hand, there was the fear that, standing outside the auto repair shop, Tadeo, in his grease-stained overalls, would see me. But on the other hand, I was plagued by the more intense fear that I would never again see Tadeo, standing outside the repair shop and wearing his grease-stained overalls.

[3666 words]

This story has been published three times::

Spanish

Con la de palo (2017). Revista de la Academia Norteamericana de la Lengua Española. lean®anle, Nueva York, vol. VI, n.º 12, julio-diciembre 2017, págs. 482-490.

Con la de palo (2019). El Malpensante, n.º 204, Bogotá, febrero de 2019, págs. 74-79.

Italian

Con la gamba inutile (2021). (traducción al italiano de Enzo Citterio). Osservatorio Letterario N.º 139-140, Ferrara (Italia), marzo-aprile/maggio-giugno 2021, págs. 14-17.

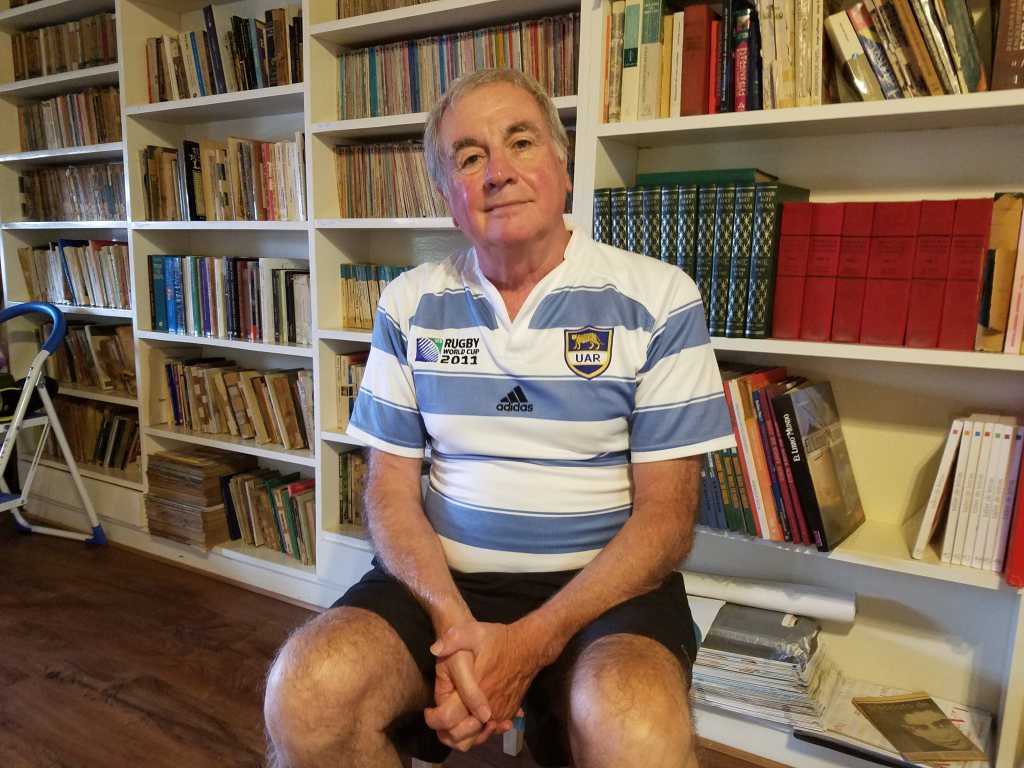

Datos biográficos

Fernando Sorrentino nació en Buenos Aires el 8 de noviembre de 1942. Es profesor de Lengua y Literatura.

Que linda historia del autor, de su infancia en Buenos Aires y de las lecciones que aprendio del deporte nacional, tan importante como una religion