First of all, published poet and contributor Tao Yucheng is still hosting a poetry contest, open to all readers of Synchronized Chaos Magazine.

Synchronized Chaos Poetry Contest: We seek short, powerful, imaginative, and strange poetry. While we welcome all forms of free verse and subject matter, we prefer concise work that makes an impact.

Guidelines: Submit up to five poems per person to taoyucheng921129@proton.me. Each poem should not exceed one page (ideally half a page or less). All styles and themes welcome. Deadline for submissions will be in early March.

Prizes: First Place: $50 Second Place: $10, payable via online transfer. One Honorable Mention. Selected finalists will be published in Synchronized Chaos Magazine.

Also, past contributor Alexander Kabishev is seeking international poems of four lines each on the theme of friendship for a global anthology. The anthology, Hyperpoem, will be published by Ukiyoto Press and a presentation of the poem will take place in Dubai in August 2026.

Kabishev says the new vision of the project goes beyond commercial frameworks, aiming to become an international cultural and humanitarian movement, with the ambitious goal of reaching one million participants and a symbolic planned duration of one thousand years.

The focus is on promoting international friendship, respect for the identity of all peoples on Earth, and building bridges of understanding between cultures through poetry and its readers.

Please send poems to Alexander at aleksandar.kabishev@yandex.ru

This month’s issue asks the question, “Who Will We Become?” Submissions address introspection, spiritual searching, and moral and relational development and decision-making.

This issue was co-edited by Yucheng Tao.

Sajid Hussain’s metaphysical, ethereal poetry, rich with classical allusions, reminds us of the steady passage of time.

Jamal Garougar’s New Year reflection emphasizes ritual, spirituality, and the practices of patience and peace. Taylor Dibbert expresses his brief but cogent hope for 2026.

Dr. Jernail S. Anand’s spare poetry illustrates the dissolution of human identity. Bill Tope’s short story reflects on memory and grief through the protagonist’s recollection of his late school classmate. Turkan Ergor considers the depth of emotions that can lie within a person’s interior. Sayani Mukherjee’s poem on dreams lives in the space between waking thought and imaginative vision. Stephen Jarrell Williams offers up a series of childhood and adult dreamlike and poetic memories. Alan Catlin’s poem sequence renders dreams into procedural logic: how fear, guilt, memory, and culture behave when narrative supervision collapses. Priyanka Neogi explores silence itself as a creator and witness in her poetry. Duane Vorhees’ rigorous poetic work interrogates structure: individuality, myth, divinity, agency, culture. Tim Bryant analyzes the creative process and development of craft in Virginia Aronson’s poetic book of writerly biographies, Collateral Damage.

Nurbek Norchayev’s spiritual poetry, translated from English to Uzbek by Nodira Ibrahimova, expresses humility and gratitude to God. Timothee Bordenave’s intimate devotional poetry shares his connection to home and to his work and his feelings of gratitude.

Through corrosive imagery and fractured music, Sungrue Han’s poem rejects sacred authority and reclaims the body as a site of sound, resistance, and memory. Shawn Schooley’s poem operates through liturgical residue: what remains after belief has been rehearsed, delayed, or partially evacuated. Slobodan Durovic’s poem is a high-lyric, baroque lament, drawing from South Slavic oral-poetic density, Biblical rhetoric, and mythic self-abasement.

Melita Mely Ratkovic evokes a mystical union between people, the earth, and the cosmos. Jacques Fleury’s work is rich in sensory detail and conveys a profound yearning for freedom and renewal. The author’s use of imagery—“fall leaf,” “morning dew,” “unfurl my wings”—evokes a vivid sense of life’s beauty and the desire to fully experience it. James Tian speaks to care without possession, love through distance and observation. Mesfakus Salahin’s poem evokes a one-sided love that is somewhat tragic, yet as eternal as the formation of the universe, as Mahbub Alam describes a love struggling to exist in a complicated and wounded world. Kristy Ann Raines sings of a long-term, steady, and gallant love.

Lan Xin evokes and links a personal love with collective care for all of humanity. Ri Hossain expresses his hope for a gentler world by imagining changed fairy tales. Critic Kujtim Hajdari points out the gentle, humane sensibility of Eva Petropoulou Lianou’s poetry. Brian Barbeito’s lyric, understated travel essay passes through a variety of places and memories. Anna Keiko’s short poem shares her wish for a simple life close to nature. Christina Chin revels in nature through sensual, textured haikus.

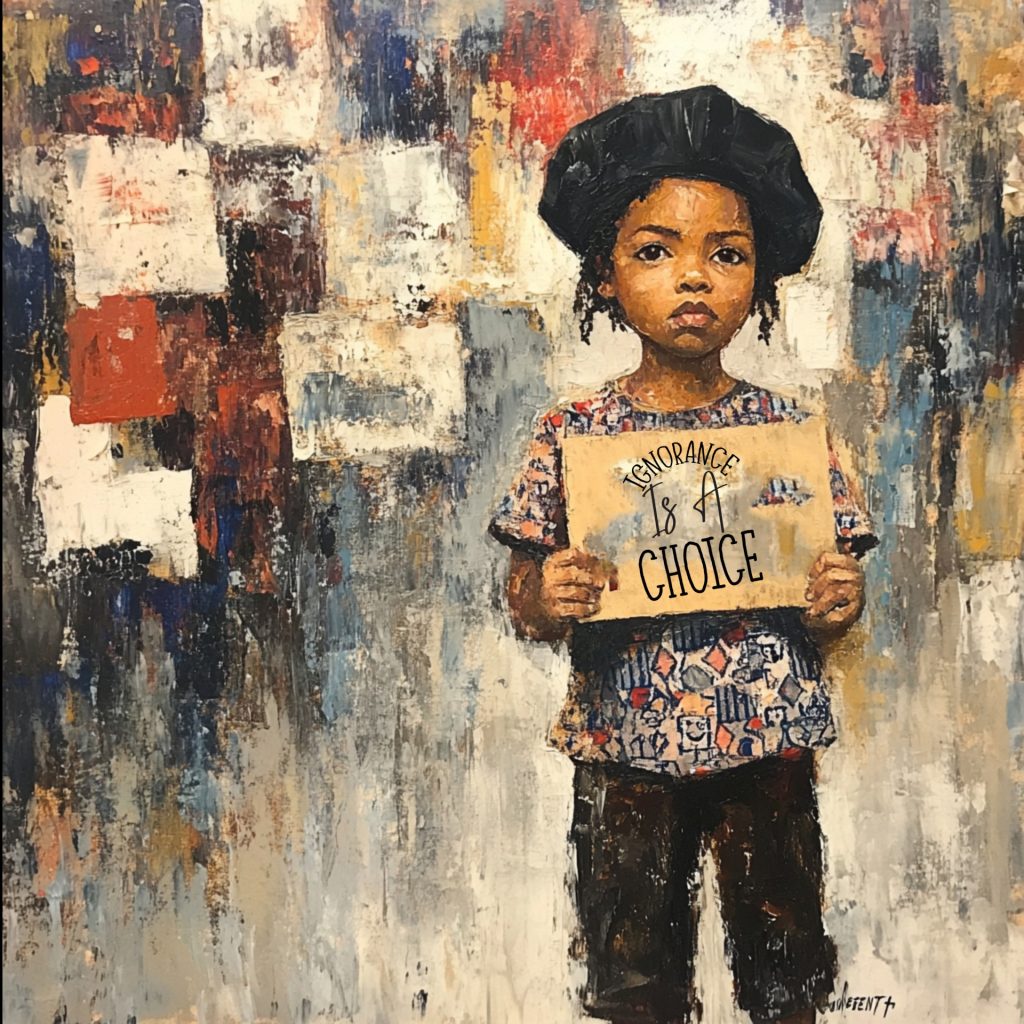

Doniyorov Shakhzod describes the need for healthy and humane raising of livestock animals. g emil reutter hits us on the nose with cold weather and frigid social attitudes towards the suffering of the poor and working classes. Patricia Doyne lampoons authoritarian tendencies in the American government. Eva Petropoulou Lianou reminds us that we cannot truly enjoy freedom without a moral, peaceful, and just society. Sarvinoz Giyosova brings these types of choices down to a personal level through an allegory about different parts of one person’s psychology.

Dr. Jernail S. Anand critiques societal mores that have shifted to permit hypocrisy and the pursuit of appearances and wealth at all costs. Inomova Kamola Rasuljon qizi highlights the social and medical effects and implications of influenza and its prevention. Sandip Saha’s work provides a mixture of direct critique of policies that exploit people and the environment and more personal narratives of life experiences and kindness. Gustavo Gac-Artigas pays tribute to Renee Nicole Good, recently murdered by law enforcement officers in the USA.

Dr. Ahmed Al-Qaysi expresses his deep and poetic love for a small child. Abduqahhorova Gulhayo shares her tender love for her dedicated and caring father. Qurolboyeva Shoxista Olimboy qizi highlights the connection between strong families and a strong public and national Uzbek culture. Ismoilova Jasmina Shavkatjon qizi’s essay offers a clear, balanced meditation on women in Uzbekistan and elsewhere as both moral architects and active agents of social progress, grounding its argument in universal human values rather than abstraction.

Dilafruz Muhammadjonova and Hilola Khudoyberdiyeva outline the contributions of Bekhbudiy and other Uzbek Jadids, historical leaders who advocated for greater democracy and education. Soibjonova Mohinsa melds the poetic and the academic voices with her essay about the role of love of homeland in Uzbek cultural consciousness. Dildora Xojyazova outlines and showcases historical and tourist sites in Uzbekistan. Zinnura Yuldoshaliyeva explicates the value of studying and understanding history. Rakhmanaliyeva Marjona Bakhodirjon qizi’s essay suggests interactive and playful approaches to primary school education. Uzbek student Ostanaqulov Xojiakba outlines his academic and professional accomplishments.

Aziza Joʻrayeva’s essay discusses the strengths and recent improvements in Uzbekistan’s educational system. Saminjon Khakimov reminds us of the importance of curiosity and continued learning. Uzoqova Gulzoda discusses the importance of literature and continuing education to aspiring professionals. Toychiyeva Madinaxon Sherquzi qizi highlights the value of independent, student-directed educational methods in motivating people to learn. Erkinova Shahrizoda Lazizovna discusses the diverse and complex impacts of social media on young adults.

Alex S. Johnson highlights the creative energy and independence of musician Tairrie B. Murphy. Greg Wallace’s surrealist poetry assembles itself as a bricolage of crafts and objects. Noah Berlatsky’s piece operates almost entirely through phonetic abrasion and semantic sabotage, resisting formal logic and evoking weedy growth. Fiza Amir’s short story highlights the level of history and love a creative artist can have for their materials. Mark Blickley sends up the trailer to his drama Paleo: The Fat-Free Musical. Mark Young’s work is a triptych of linguistic play, consumer absurdity, and newsfeed dread, unified by an intelligence that distrusts nostalgia, coherence, and scale. J.J. Campbell’s poetry’s power comes from the refusal to dress things up, from humor as insulation against pain. On the other end of the emotional spectrum, Taghrid Bou Merhi’s essay offers a lucid, philosophically grounded meditation on laughter as both a humane force and a disruptive instrument, tracing its power to critique, heal, and reform across cultures and histories. Mutaliyeva Umriniso’s story highlights how both anguish and laughter can exist within the same person.

Paul Tristram traces various moods of a creative artist, from elation to irritation, reminding us to follow our own paths. Esonova Malika Zohid qizi’s piece compares e-sports with physical athletics in unadorned writing where convictions emerge with steady confidence. Dr. Perwaiz Shaharyar’s poetry presents simple, defiant lyrics that affirm poetry as an indestructible form of being, embracing joy, exclusion, and madness without apology.

Ozodbek Yarashov urges readers to take action to change and improve their lives. Aziza Xazamova writes to encourage those facing transitions in life. Fazilat Khudoyberdiyeva’s poem asserts that even an ordinary girl can write thoughtful and worthy words.

Botirxonov Faxriyor highlights the value of hard work, even above talent. Taro Hokkyo portrays a woman finding her career and purpose in life.

We hope that this issue assists you, dear readers, in your quest for meaning and purpose.