SOLACE OF MOONLIGHT To be kissed by the moonlight Is such a glowing grace To be caressed by stars Is such a life Draped In darkened blue Dancing from mercury to Venus What an honest dance. To be found by the light of the moon And loved under a blackened sky Let the sun forget about me It never heard me crying Not today. As there is something so special about the moonlight Like it was made just for me Because no matter how bad things go I have the moon as my company.

Monthly Archives: October 2022

Poetry from Sayani Mukherjee

Simple Ruins among saplings A crescent washed glow Global apothecary, time's healer Crashed out in Woolen sweaters. Disasters gravity's rainbow A Forlorn runaway train A crumpled cup of waiting Soon muzzles out. A thin beat of a shy evening They all called her. Now the words are naked Unzipped motion Cinema like it moves away Ties the gift in a parcel A matchbox to keep the little roses safe Laced pearled of few words A minimalist safebox Frees the burden In little simple emotions. Solace By Sayani Mukherjee Nascent images booned My brewed morning With words as if fragmented clothes I thought, They will play with me- A criss cross algorithm Between simplicity and public vain And then will appear A blessed halo And silver whispers that will somehow ring by my side With nightshades and soft clouds- A brimful of common poetry. Because, only I know the voice Natural, unscarred within And the serene utterance As it colours the morning prayer. Then, a cradled shadow A wet dripped morning, Raindrops two or three, And a cottage of green simplicity. The rugged path will be my destiny It is not just worldly wisdom for my wishy washy tale But my whimsy haze And my romantic spree An eternal wish for an April spring With my brewed morning And my winged pen Leading my green path Towards my bundled sky And a grim, earthy solace.

Synchronized Chaos October 2022: A PAN-LATIN AFFAIRE *

by Synchronized Chaos Guest Editor Lorraine Caputo

From mid-September to mid-October, Hispanic / Latinx Heritage Month is observed, celebrating the culture and history of Spanish-speakers of either side of the ocean, in Europe and in the Americas.

This month starts off with the observances of the independence from Spain of the Central American Republics – Guatemala, El Salvador, Honduras, Nicaragua and Costa Rica – on 15 September, and Mexico’s Independence from that colonial power on 16 September. Chile celebrates its Independence and Fiestas Patrias on 18 and 19 September.

Also during this month – on 12 October – is the former Columbus Day, observed in Spain, Italy and the Americas. Now this date has different names in recognition of the Indigenous nations that populated the Americas before the 1492 Spanish invasion: Día de la Raza (El Salvador, Uruguay), Día de las Culturas (Day of the Cultures, Costa Rica), Día de la Resistencia Indígena (Day of Indigenous Resistance, Venezuela), Día de los Pueblos Originarios y el Diálogo Intercultural (Indigenous Peoples and Intercultural Dialogue Day, Peru), and Día del Respeto a la Diversidad Cultural (Day of Respect for Cultural Diversity, Argentina).

Synchronized Chaos’ Hispanic / Latinx Heritage Month literary feast also invites the other Latin cousins – French, Italian, Portuguese-Brazilian, Romanian, Catalan – to participate.

So, come join our party! ¡Buen provecho!

In his delightful short story “Mabel’s Library,” Fernando Sorrentino portrays the love of reading and of one’s personal book collection, in both life … and death.

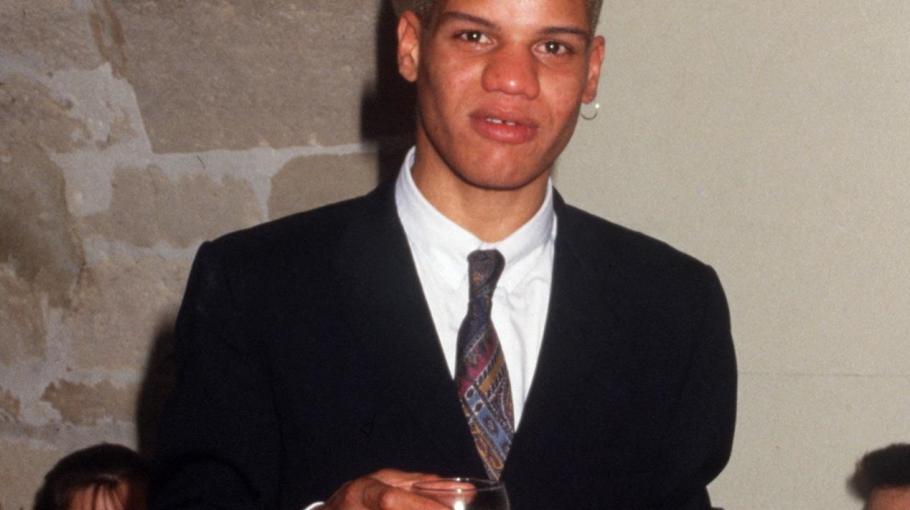

In “Why (Do) White French Institutions Have a Hard Time Admitting The Impact Of Racism/Colonialism In Black Serial Killers’ Psychological Damage?: The Case of Thierry Paulin”, Victoria Kabeya asks a question that is common in this “post-colonial / post-racial” world, that [former] colonial powers proclaim – whether it be France, Spain, Portugal, Britain, the US, or …

Gabriella Garofalo’s “Blue Scenes” is a suite of poems woven with blue and so many colors of lives and their trails / travails. (Read this poem aloud – the rhythm will carry you …). In “Flames in the Wind”, Andrea Soverini captures the spirit of what is life – a perfect allegory for the upcoming Día de los Muertos.

The duality of what heals us – yet poisons us is presented in Diosa Xochiquetzalcoatl’s poem, “Café de la Olla.” Meanwhile, with his pair of poems, Roberto Rocha invites us to his barrio to witness the contradictions that are the “American Dream,” and the realities versus the stereotypes of what a Chicanx is.

With his essay “When the Stars First Came Out – Carmen & Bidu,” Josmar Lopes recounts the life and fame of two great Brazilian singers: the lovely Bidu Sayão, who is virtually unknown in the United States, and the electric Carmen Miranda, who became a Hollywood star.

In “Ballad of the Checkboard”, Ana M. Fores Tamayo asks who should be stepping back – the white or the brown-skinned, pawns in a chess game dictated by a white judge. “Fishing in the Green” is a surreal landscape of different lives / lifestyles existing parallel. “Matrimony” is a celebration of love. In “The Three Fates” / “Los Tres Destinos,” Fores Tamayo meditates on the passing of time … and life.

Despite her mother’s well-founded misgivings, Linda S. Gunther gets to see her father once again, at least for a short while. This “Rockefeller Center Reunion” is a story that is well-known by many children of divorced families.

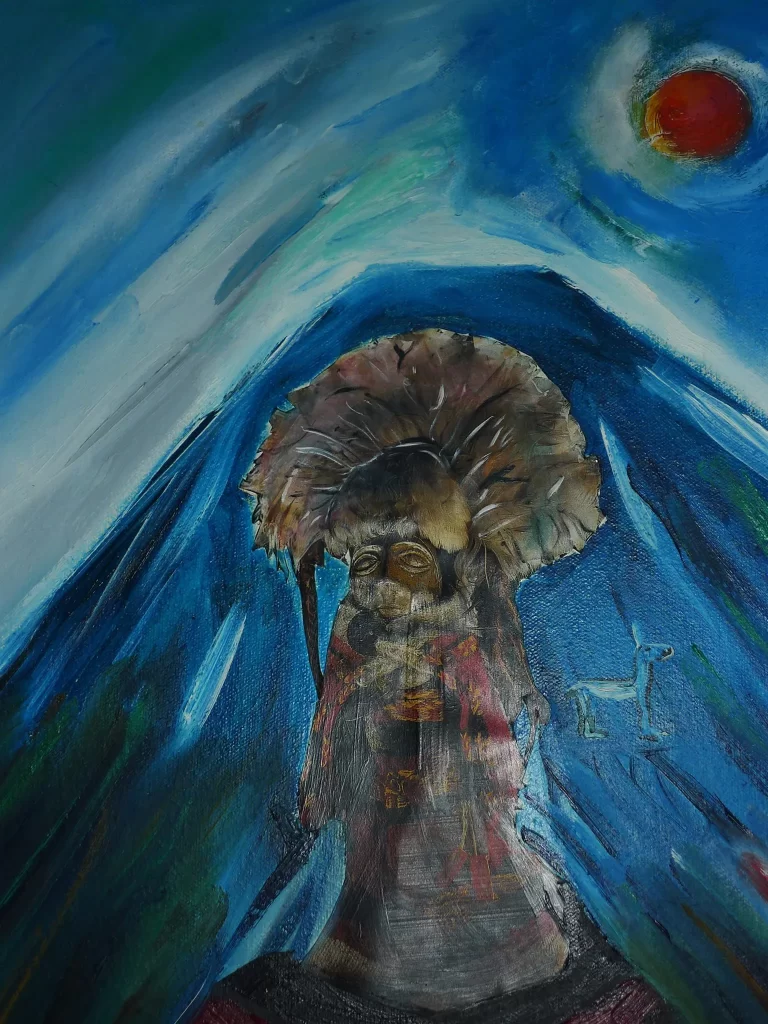

Diana Magallón‘s trio of images portray dancelike movements across multiple dimensions – trompe l’oeil (trick of the eye), hieroglyphics, and 3-D syncopations quiver with indigenous flair. Magallón and Jeff Crouch then offer a quartet of images that dispel the smoke of “100 Días de Humo” (100 Days of Smoke).

Does dancing cause one to fall into an everlasting love? Daniel de Culla answers that question for us in his poem “El Bailaré” / “The I’ll Dance.”

* This edition was inspired by the work of Fernando Sorrentino as well as the principle of Pan-Latinidad.

Short story from Fernando Sorrentino

Mabel’s Library (La biblioteca de Mabel) 1. As the sufferer of a certain classificatory mania, from my adolescence I took the care of cataloguing the books in my library. By my fifth year of secondary school, I already possessed a reasonable, for my age, number of books: I was approaching six hundred volumes. I had a rubber stamp with the following legend: Fernando Sorrentino’s Library Volume nº ______ Registered on: ______ As soon as a new book arrived, I stamped it, always using black ink, on its first page. I gave it its corresponding number, always using blue ink, and wrote its date of acquisition. Then, imitating the old National Library’s catalogue, I entered its details on an index card which I filed by alphabetical order. My sources of literary information were the editorial catalogues and the Pequeño Larousse Ilustrado. An example at random: in some collections from the various editors were Atala. René. The Adventures of the Last Abencerage. Sparked by such profusion and because Chateaubriand on the pages of the Larousse seemed to have a great importance, I acquired the book in the edition of Colección Austral from Espasa-Calpe. In spite of these precautions, those three stories turned out to be as unbearable to me as they were so evanescent. In contrast with these failures, there were also total successes. In the Robin Hood collection, I was fascinated by David Copperfield and, in the Biblioteca Mundial Sopena, by Crime and Punishment. Along the even-numbered side of Santa Fe Avenue, a short distance from Emilio Ravignani Street, was the half-hidden Muñoz bookshop. It was dark, deep, humid and moldy, with wooden creaking planks. Its owner was a Spanish man about sixty years old, very serious, and somewhat haggard. The only sales assistant was the person who used to serve me. He was young, bold and prone to errors and without much knowledge of the books he was asked about nor where they were located. His name was Horacio. At the moment I entered the premises that afternoon, Horacio was rummaging around some shelves looking for heaven knows what title. I managed to learn that a tall and thin girl had enquired about it. She was, in the meantime, glancing at the wide table where the second hand books were exhibited. From the depths of the shop, the owner’s voice was heard: ‘What are you looking for now, Horacio?’ The adverb now showed some bad mood. ‘I can’t find Don Segundo Sombra, Don Antonio. It is not on the Emecé shelves’. ‘It is a Losada book, not Emecé; look on the shelves of the Contemporánea’. Horacio changed the location of his search and, after a great deal of exploration, he turned toward the girl and said to her: ‘No, I am sorry; we have no Don Segundo left’. The girl lamented the fact, said she needed it for school and asked where she could find it. Horacio, embarrassed before of an unfathomable enigma, opened his eyes widely and raised his eyebrows. Luckily, don Antonio had overheard the question: ‘Around here’, he answered, ‘it is very hard. There are no good bookshops. You will have to go to the centre of town, to El Ateneo, or some other in Florida o Corrientes. Or perhaps near Cabildo and Juramento.’ Disappointment upset the girl’s face. ‘Forgive me for barging in’, I said to her. ‘If you promise to take care of it and return it to me, I can lend you Don Segundo Sombra.’ I felt as if I was blushing, as if I had been inconceivably audacious. At the same time, I felt annoyed with myself for having given way to an impulse that was contrary to my real feeling. I love my books and hate lending them. I don’t know what exactly the girl answered, but after some squeamishness she ended up accepting my offer. ‘I have to read it immediately for school’, she explained, as if to justify herself. I then learnt that she was in the third year in the women’s college at Carranza Street. I suggested that she accompanied me home and I would let her have the book. I gave her my full name, and she gave me hers. She was called Mabel Mogaburu. Before starting our journey, I accomplished what had taken me to the Muñoz bookshop. I bought The Murders in the Rue Morgue. I had already the Tales of the Grotesque and Arabesque and, with much delight, decided to dwell once again on the fiction of Edgar Allan Poe. ‘I don’t like him at all’, Mabel said. ‘He is gruesome and full of effect, always with those stories of murders, of dead people, of coffins. Cadavers don’t appeal to me.’ While we walked along Carranza toward Costa Rica Street, Mabel spoke full of enthusiasm and honesty about her interest in or, rather, passion for literature. On that point, there was a deep affinity between us but, of course, she mentioned authors who converged in and diverged from our respective literary loves. Although I was two years older than her, it seemed to me that Mabel had read considerably more books than me. She was a brunette, taller and thinner than what I had thought in the bookshop. A certain diffused elegance adorned her. The olive shade of her face seemed to mitigate some deeper paleness. The dark eyes were fixed straight on mine, and I found it hard to withstand the intensity of that steady stare. We arrived at my door in Costa Rica Street. ‘Wait for me on the pavement; I’ll bring you the book right away.’ And I did find the book instantly as, because of a question of homogeneity, I had (and still have) my books grouped by collection. Thus, Don Segundo Sombra (Biblioteca Contemporánea, Editorial Losada) was placed between Kafka’s The Metamorphosis and Chesterton’s The Innocence of Father Brown. Back in the street, I noticed, although I know nothing about clothes, that Mabel was dressed in a somewhat, shall we say, old-fashioned style, with a greyish blouse and black skirt. ‘As you can see’, I told her, ‘this book looks brand new, as if I had just bought it a second ago in don Antonio’s bookshop. Please take care of it, put a cover on it, don’t fold the pages as a marker and, especially, don’t even think of writing a single comma on it.’ She took the book—with such long and beautiful hands—with what I thought was certain mocking respect. The volume, of an impeccable orange colour, looked as if it had just left the press. She turned the pages for a while. ‘But I see that you do write on books’, she said. ‘Certainly, but I use a pencil, with a small and very meticulous writing, those are notes and useful observations for enriching my reading. Besides’, I added, slightly irritated, ‘the book belongs to me and I give it any use I like’. I immediately regretted my rude remark, as I saw mortification in Mabel’s face. ‘Well, if you don’t trust me, I prefer not to borrow it.’ And she handed it back to me. ‘No, not at all, just take care of it, I trust your wisdom.’ Oh’, she was looking at the first page, ‘You have your books classified?’ And she read in loud voice, not jokingly: ‘Library of Fernando Sorrentino. Volume number 232. Registered on: 23/04/1957.’ ‘That’s right, I bought it when I was in the second year of secondary. The teacher requested it for our work in Spanish Lit classes.’ ‘I found the few short stories I’ve read by Güiraldes rather poor. That’s why I never thought of getting Don Segundo.’ ‘I think you are going to like it, at least there are no coffins or cursed houses or people buried alive. When do you think you’ll be returning it?’ ‘You’ll have it back within a fortnight, as radiant’—she emphasised—‘as you are giving it to me now. And to make you feel more relaxed, I am writing my address and telephone number.’ ‘That’s not necessary,’ I said, out of decorum. She took out a ballpoint pen and a school notebook from her purse and wrote something on the last page, she tore it out and I accepted it. To be surer, I gave her my telephone number, too. ‘Well, I am very grateful… I am going home now.’ She shook my hand (no kisses at that time as is the way now) and she walked toward the Bonpland corner. I felt some discomfort. Had I made a mistake by lending a book dear to me to a completely unknown person? The information she had given me, could it be apocryphal? The page in the notebook was squared; the ink, green. I searched the phonebook for the name Mogaburu. I sighed with relief, a Mogaburu, Honorio was listed next to the address written by Mabel. I placed a card between The Metamorphosis and The Innocence of Father Brown with the legend Don Segundo Sombra, missing, lent to Mabel Mogaburu on Tuesday 7th of June 1960. she promised to return it, at the latest, on Wednesday 22nd of June. Under it, I added her address and phone number. Then, on the page of my agenda for the 22nd of June, I wrote: Mabel. Attn! Don Segundo. 2. That week and the next went by. I continued with my usual, mostly unwanted, activities as a student in my last year of secondary. We were on the afternoon of Thursday the 23rd. As it usually happens to me, even to this day, I make annotations on my agenda that I later forget to read. Mabel had not called me to return the book or, is that was the case, to ask me to extend the loan. I dialed Honorio Mogaburu’s number. At the other end, the bell rang up to ten times but nobody answered. I hung up the phone but called again many times, at different times, with the same fruitless result. The process was repeated on Friday afternoon. Saturday morning, I went to Mabel’s home, on Arévalo Street, between Guatemala and Paraguay. Before ringing the bell, I watched the house from across the street. A typical Palermo Viejo construction, the door in the middle of the facade and a window on each side. I could see some light through one of them. Would Mabel be in that, a room occupied with her reading…? A tall dark man opened the door. I imagined he must be Mabel’s grandfather. ‘What can I do for you…? ‘I beg your pardon. Is this Mabel Mogaburu’s home?’ ‘Yes, but she is not here right now. I am her father. What did you want her for? Is it something urgent?’ ‘No, it’s nothing urgent or very important. I had lent her a book and… well, I am needing it now for…’—I searched for a reason—‘a test I have on Monday.' ‘Come in, please.’ Beyond the hallway, there was a small living room that appeared poor and old-fashioned to me. A certain unpleasant smell of stale tomato sauce mixed with insecticide vapours floated in the air. On a small side table, I could see the newspaper La Prensa, and there was a copy of Mecánica Popular. The man moved extremely slowly. He had a strong resemblance to Mabel, he had the same olive skin and hard stare. ‘What book did you lend her?’ ‘Don Segundo Sombra.’ ‘Let’s go into Mabel’s room and see if we can find it’. I felt a little ashamed for troubling this elderly man that I judged unfortunate and who lived in such sad house. ‘Don’t bother’, I told him. ‘I can return some other day when Mabel is here, there is no rush.’ ‘But didn’t you say that you needed it for Monday…?’ He was right, so I chose not to add anything. Mabel’s bed was covered with an embroidered quilt of a mitigated shine. He took me to a tiny bookcase with only three shelves. ‘These are Mabel’s books. See if you can find the one you want’. I don’t think there were one hundred books there. There were many from Editorial Tor among which I recognized, because I too had that edition from 1944, The Phantom of the Opera with its dreadful cover picture. And I identified other common titles, always in rather old editions. But Don Segundo wasn’t there. ‘I took you into the room so you could stay calm’, said the man. ‘But Mabel hasn’t brought books for many years to this library. You have seen that these are pretty old, right?’ ‘Yes, I was surprised not to see more recent books…’ ‘If you agree and have the time and the inclination’, he fixed his eyes on me and made me lower mine, ‘we can settle this matter right now. Let’s look for your book in Mabel’s library.’ He put on his glasses and shook a key ring. ‘In my car, we’ll be there in less than ten minutes.’ The car was a black and huge DeSoto that I imagined was a ’46 or ’47 model. Inside, it smelled of enclosure and stale tobacco. Mogaburu went around the corner and enter Dorrego. We soon reached Lacroze, Corrientes, Guzmán and we entered the inner roads of the Chacarita cemetery. We stepped down and started walking along cobbled paths. My blessed or cursed literary curiosity urged me to follow him now through the area of the crypts without asking any questions. In one of them with the name MOGABURU on its facade, he introduced a key and opened the black iron door. ‘Come on,’ he said, ‘don’t be afraid.’ Although I didn’t want to, I obeyed him, at the same time resenting his allusion to my supposed fear. I entered the crypt and descended a small metal ladder. I saw two coffins. ‘In this box,’ the man pointed to the lower lit, ‘María Rosa, my wife, who died the same day Frondizi was made president.’ He tapped the top several times with his knuckles. ‘And this one belongs to my daughter, Mabel. She died, the poor thing, so young. She was barely fifteen when God took her away in May of 1945. Last month, it was fifteen years since her death. She would be 30 now.’ He leaned slightly over the coffin and smiled, as someone who is sharing a fond memory. ‘Unfair Death couldn’t keep her away from her great passion, literature. She continued restlessly reading book after book. Can you see? Here is Mabel’s other library, more complete and up to date than the one at home.’ True, one wall of the crypt was covered almost from the floor to the ceiling, I assume because of lack of space, by hundreds of books, most of them in a horizontal position and in double rows. ‘She, methodical person that she was, filled the shelves from top to bottom and left to right. Therefore, your book, being a recent borrowing, must be on the half full shelf on the right’. A strange force lead me to that shelf, and there it was, my Don Segundo. ‘In general’, Mogaburu continued, ‘not many people have come to claim the borrowed books. I can see you love them very much.’ I had fixed my eyes on the first page of Don Segundo. A very large green X blotted out my stamp and my annotation. Under it, with the same ink and the same careful writing in print letters there were three lines: Library of Mabel Mogaburu Volume 5328 7th of June of 1960 ‘The bitch!’ I thought, ‘Think how earnestly I asked her not to write even a comma.’ ‘Well, that’s the way things go’, the father was saying. ‘Are you taking the book or leaving it as a donation to Mabel’s library?’ Angrily and rather abruptly, I replied: ‘Of course I am taking it with me, I don’t like getting rid of my books.’ ‘You are doing right,’ he replied while we climbed the ladder. ‘Anyway, Mabel will soon find another copy.’ [From: How to Defend Yourself against Scorpions, Liverpool, Red Rattle Books, 2013. - Translated from the Spanish by Gustavo Artiles Other versions Spanish (original text) La biblioteca de Mabel (2013). Delicias al Día (dir.: Agustín Díez Ferreras), Valladolid (España), marzo 2013, págs. 8-9. La biblioteca de Mabel (2013). Gramma (directora: Alicia Sisca), Universidad del Salvador; Facultad de Filosofía, Historia y Letras; Escuela de Letras, Buenos Aires, Nº 49, diciembre 2013, págs. 238-245. La biblioteca de Mabel (2013). En Fernando Sorrentino: Paraguas, supersticiones y cocodrilos (Verídicas historias improbables) (2013). Veracruz (México), Instituto Literario de Veracruz, El Rinoceronte de Beatriz, 2013, 140 págs. Italian La biblioteca di Mabel (2013). (translation of Inchiostro team). Inchiostro. Rivista di storie e racconti da leggere e da scrivere (direttore: Giampiero Dalle Molle), Anno 19, Nº 3-4, Verona (Italia), maggio-dicembre 2013, pagine. 11-14. German Die Bibliothek von Mabel (2014). (translation of Sandra Fuertes Romero y Jana Wahrendorff). In Fernando Sorrentino: Problema resuelto. Cuentos argentinos de Fernando Sorrentino / Problem gelöst. Argentinische Erzählungen von Fernando Sorrentino (2014), Düsseldorf, dup (düsseldorf university press), 250 Seiten.

Read Fernando’s bio HERE.

Essay from Victoria Kabeya (V KY)

Why (Do) White French Institutions Have a Hard Time Admitting The Impact Of Racism/Colonialism In Black Serial Killers' Psychological Damage?: The Case of Thierry Paulin France's most notorious serial killer was a black man. Thierry Paulin. Born in 1963, in Martinique, the young man left the earth at only twenty-five, leaving behind him a horrific legacy. Between 1984 and 1987, the year of his arrest, Paulin murdered twenty-one old ladies in Eastern Paris to steal their money and fund his lavish lifestyle. However, though he admitted to having murdered twenty-one old ladies, the French police had enough evidence to suggest he would have actually killed up to forty of them, with a total of sixhundred attacks and theft. Thierry Paulin and Guy Georges are still the only two Afro-descendant serial killers in France to this day, a nation whose phenomenon of mass murder is still rare. Both men share the same background, were mixed-race, abandoned by their parents, evolved in a white French conservative society which rejected them for being Afro-descendants and did not have (a) place in psychiatry to treat their specific conditions. If a few documentaries were made about Paulin, and a few books were written about him, only white people were behind these projects. In the tradition of the French media in the 1980s, they did not approach Paulin as the failed human being he was, but as an animal exposed in a freak show from whom any institutional power wished to exploit for their own gain. Indeed, in the 1980s French society, a time when Black people were even more invisible, the arrest of Paulin appeared as a surprise. In that sense, the French journalists, not only exploited the killer and the victims to feed sensationalism, but they also needed to further and create the image of a monster who had appeared from nowhere in French society to attack innocent white old ladies. In all the articles written about him by the journalists and experts, Paulin was introduced as a total enigma, when his downfall was never shrouded in any mystery, as it rather took root in a specific side the French institutions did not want to dive into. Thierry Paulin highlighted the hypocrisy of French society, whether in justice or law, regarding the treatment of Caribbean groups in the postcolonial migration waves which started massively in the 1960s. None of the journalists who attempted to focus on his history ever talked about the brutality of the Caribbean experience. Indeed, Paulin's fall into mass murder was directly linked to and caused by the tragedy and the failure of the Afro-Caribbean immigration experience in France at that specific time. Upon studying his case, the medical institutions even failed to understand the structure of Caribbean families - especially when it came to family abuse inherited from slavery - in order to evaluate the damage it had caused in Paulin's psyche. In the racist white French landscape of that time, Paulin had to remain this freak, light-skinned, mixed-race, young gay mass murderer and occasional drag-queen, who had suddenly decided to crush the lives of innocent and helpless old white women. Therefore, if a few modern white journalists have tried to understand the mind of Paulin, they still refuse to focus on the impact of racism, the Caribbean immigration experience, poverty, social isolation and psychological damage of the black mind. First of all, this hypocrisy of the white French institutions can be explained by history itself. Though France was always a great colonial power which greatly contributed to the Slave Trade, the French authorities are no stranger to the black body. Yet, contrary to the Northern European white colonial powers which furthered the concept of apartheid, through racial separation, Latin powers such as France rather focused on the idea of universalism, métissage (race-mixing) in order to annihilate any revindication from the colonized groups. As a consequence, if the French institutions do not recognise the differences in races, due to this principle of universalism, then racism can not be a valid argument when it comes to the damage of one's black mind. This hypocrisy helps the French institutions to reject their role in colonialism (and) slavery since they can hide behind the principle of universality. Thierry Paulin never had the possibility to be diagnosed, understood and perceived for who he was, due to the policy of universalism. Neither the media nor the psychiatrists wanted to know the truth but rather wanted to exploit Paulin for him to fit in their own pre-conceived ideas regarding the murder. Paulin did not kill because he was a born-killer or a born-beast, but was psychologically and mentally ill. Yet, such approbation of his mental health was not pushed at the forefront by the media as the journalists only highlighted any degree of sensationalism. When interviewed by racist psychiatrist Serge Bornstein in 1988 and in early 1989 before he passed away of AIDS in his hospital-prison cell of Bichat, Paulin was described as arrogant towards the medical staff. In reality, a narcissist, he knew the scheme which was being displayed before his eyes. All wanted to exploit him and he refused to give them any secret, especially from his childhood. Yet, one thing should be mentioned. If the judiciary and political institutions promote the idea of universalism, such ideology exists in medicine, especially in psychiatry. Though this sector claims not to see race and differences, the French medicine was based upon colonial and racist principles which date back to the Enlightenment era in the 18th century. Later, cases such as that of the Venus Hottentot whose remains were kept and exposed until the 1970s, would illustrate our argument. The black body in French medicine is invisible, and such reality comes as even more shocking since France has been a great colonial power. In that sense, Paulin was given techniques of analysis which were made and conceived for white male criminals. Paulin, as a mixed-race Caribbean young man, was the product of another reality which is that of the impact of slavery and French colonialism on the Caribbean societies and thus, in families. If the impact of the slave trade and its oppressive system were to be recognised, the French societies should have been forced to acknowledge that Paulin, just like Guy Georges, were not "monsters" born out of nowhere, but the pure products of France's historical, social and political failures regarding the treatment of black minorities, whether mixed-race or not. Paulin's mind was never analyzed by a black psychiatrist, but rather by incompetent white French psychiatrists who had no knowledge of black Caribbean societies at all. Both the psychiatrists and media refuse to admit that racism, race and black historical oppression can not only destroy a family's structure but also weaken the mind of a black individual living in the Western sphere. Thanks to social media, more and more black women in France took to Twitter to denounce their mistreatment in French medicine. Most of them had been the victims of the Syndrome Méditerranéen (translated to Mediterranean Syndrome). The latter refers to the constant mistreatment of black patients whose symptoms of pain are not initially believed to be true by the white doctors who are in charge of them. The group members are, through prejudice, always said to lie and exaggerate their pain. In 2017, French-Congolese Naomi Musenga lost her life for this reason. As she was suffering from a hemorrhage, she called the SAMU and a white female dispatcher mocked her and her symptoms, refusing to take her seriously. The young lady eventually died of her inner pain and struggle. The medical structure at the time of Paulin was not only late, but never studied Paulin's dysfunctional family background, his mother's psychiatric identity or even thought of understanding him through the Caribbean experience, as they rather chose to remain focused on their racist views, using the brutality of the murders to support their diagnosis. On the contrary, in the United Kingdom, another great European colonial power, white psychiatrists had written reports, as early as the late 1960s, to alarm the health government on the risk of schizophrenia on Afro-Caribbean patients linked to racism, the trauma of isolation, poverty and the effect of a double identity. But France, which was always late, even when it comes to the technique of DNA, did not study its minorities at all. Paulin was thus presented as a brutal individual, when his crime history follows the pattern of a crushed Afro-Caribbean man who failed to find a place in a white French society which did not want him. The constant abuse from his family, whose members rejected him, weakened him deeply. He suffered from severe depression as a result of his parent's abandonment, hence a mental disorder which was never addressed. He never found any institutions in his youth which could have helped him heal his mental disorder and rather carried on reaching the lowest levels of his own self. He gradually became suicidal, psychotic, became a sociopath and eventually a psychopath as soon as the crime frequency increased. Paulin was not born a monster, but rather was the product of both black Caribbean and white French sociopolitical failures. Just like Guy Georges, Paulin could have been saved and possessed all the resources necessary to make it in life but he was failed in his mental state until he committed the worst. Paulin was, before anything else, a mentally ill individual who had inherited important psychological issues which are not mentioned by the French media until this day to further the racist description they made of him. The case of Paulin also helps us note one thing when it comes to the absence of black psychiatrists. Two years before Paulin was born, Frantz Fanon passed away from leukemia at the age of thirty-six. He remains, until this day, the only black Caribbean psychiatrist to have written about the impact of colonialism on the black mind, while the Black Americans had W.E.B. DuBois as early as the beginning of the 20th century. This highlights the lack of interest of white French institutions regarding the case of black psychiatry, especially when Western medicine has been tied to the capitalistic value of the minorities in the spectrum of raw capitalism. Paulin fascinated in the morbid experience for what he portrayed and not for how complex his psyche had become. There was, from the white psychiatric group, no desire of healing, understanding in order to repair any damage but they rather fed their egos as they hoped Paulin would correspond to their pre-established, fraudulent diagnosis. If the worst white French and Belgian serial killers and paedophiles were deeply analyzed even in their most repulsive actions, Paulin, a black Caribbean killer, never received such a privilege. The latter had to be exploited for sensationalism only and sexually deconstructed. If Frantz Fanon remains the only black Caribbean psychiatrist to have written about the colonized black subject in psychiatry, one problem exists regarding the silence of Paulin's community. Not one single black Caribbean intellectual, whether Aimé Césaire, Edouard Glissant or Maryse Condé, spoke out to explain or attack the media in their racist treatment of Paulin. The Caribbean community still refuses to speak on it. This silence can be understood by their history and immigrant status. At the time of Paulin, the Caribbeans had been bred to submit, fear and not question the white French authorities at all. They had no political power, no economic presence, and had massively arrived through the colonial programme which was the BUMIDOM. The Caribbeans were bred and raised to live through and for the white French gaze only. If all of them knew the real reasons behind Paulin's motivation to kill, they would choose to turn a blind eye. Plus, the homophobia of these French Caribbean societies did not encourage the members to speak on the Paulin case, thus explaining their distance from him. Yet, Thierry Paulin is not 1987. He is the 1990s, the 2000s, the 2010s, the 2020s, will be the 2030s, and 2040s as long as the questions regarding the status of the ignored Caribbean community in France is not brought up. Indeed, the Caribbean youth, decades after Paulin's death, still have to deal with the same treatment endured by their forefathers. They remain isolated and their social problems, including that of food poisoning through chlordécone, are voluntarily hidden. And though the years went by, the treatment of black patients in psychiatry is still nonexistent. As a consequence, France is not protected from the sudden emergence of a new Paulin in the years to come.

VK Y

(previously known as Victoria Kabeya)

French-Belgian author and historian of African and Middle Eastern heritage. Born in France, 1991, she began her career in 2015.

As a scholar, Kabeya’s work evolves around postcolonialism through art (mostly rap French music), the study of the Sicilian/Neapolitan subject in postcolonial Italian society, Blackness in the Arab world (Israel, Palestine, Syria, Lebanon and Iraq), the Afro-Caribbeans and Indigenous Natives in Latinized America, Race-mixing and the consequences of psychological trauma among young Black boys in the ghettos.

Purchase: V KY: libros, biografías, blogs, audiolibros

Read: VK Y, Victoria Kabeya

Poetry from Gabriella Garofalo

Blue Scenes

The other lover once they called sky

A Dionysian clangour who broke limbs,

Feelings, and hard cheese if she couldn’t hide

Crashed answers, food going rotten,

Her hunger helpless like grass,

Her dig a blue sparsely furnished

With fringe stars, tasteless food,

A twisted rough mind where limbs

Shook, and squeezed in-

Don’t wonder why, answers but a dark juice

Worse than unripe currants,

Leave her alone, go on shooting snaps

As the blue rises over deep grey walls-

Maybe your flock, my shepherd of troubled souls,

Lips scraped by honey, mayhem, deceits

Let crinkly women untangle hard secrets,

Moon, perhaps you are a woman,

Only thingie you can do

Is making claims, and demands,

Coming up with sorry tales

Of children, periods, headaches,

All the way bleating you are

Awfully sorry for being a woman-

To cap it off, first season months

Promised us answers, and hope’s damn disguise-

No more wobbling, OK?

Ask the conjuror of light

To quickly move his fingers,

Their fault as ever if soul keeps starving,

And twinges went wild like a flash

On a summer storm.

******

To S.

Was she thinking of blue screens, or last words,

When fleeing heaven, or deserting dark thingies?

Three blue hours ago she set

To lend each awakening his breath

While the Angel was touching waves,

And moving his hands to the source of life,

And in her dream clear, and so deceiving

She was healing, maybe getting into the green,

Sounds engraving on her mind for good-

If only she didn’t hate sudden lights,

And her infinite was different

From a wild lava she didn’t ask for,

The rust of flowers when it clings to limbs,

A sky dodging blue fires, hers,

Her birth, her colours held back by weeds

And a smashed clingy blue-

But regret is stalking her, that cursed evergreen,

Anytime she looks at words flowing all over limbs-

Father of the first seeds, every slight feels like a danger,

So hold your waters, give your heaven

Another look, whenever her soul whispers

That light screeches, then turns out to be

The sister of grass, and earth,

When fields grab her if she gives her words,

And breaths exist, the many red bruises

Already taken for granted.

*******

To M.W.

Great, the ice blue shock runs through you

If you brush against poetry, and a dirty ambivalence

In the morning, when blue overwhelms uneasy thoughts,

And you feel them as they twist, and even shun

Nasty questions from the sky, red whirlwinds,

A water so fed up with lovers in short

That at last she morphs into a large green wound,

An end to deals, and everlasting doubts,

But why are you so scared when the fires stay silent,

And souls vibrant at digging words don’t care

For fruits, honey, handfuls of pages no good

To the skies of desertion, in a word your cave

Where life, ever the confused noise,

Sets lips ablaze with all those endless calls to infinite-

Now it’s high time to silence the books,

Can’t you see your mind never promised

To give in to snarling winds, or clear breezes?

So don't side with them, as she has no honour,

No name to protect, she doesn't care

If they find her weird, and sometimes she laughs,

While shivering from winters, while ice blue moons

Bring back a fever never as red as you’d like,

Just a clash of colours in short bursts,

They never slake a season when dogs

Keep scenting the grass, among flowers always so idle

If she looks cheerful, but maybe a bit dead.

*******

To S.

Where the hell is his strength,

The sea looks so dazed tonight,

While they are fighting over the silverware,

And an electric blue, maybe the birth of mourning,

Is rising in the sky, yet you can hear a farewell,

Whispered as they called for the mother of life,

Bitterness climbing the stairs to hurt

The onlookers at the moon,

So many bruises, like an eclipse they shine,

Among boxes all over dispersed, neglect,

A tense elegance from a light that never chills words,

If they hand blue to souls, some dodgy drugs,

Anytime she runs high and naked

Among deceiving sounds, and a second season

Raids answers much faster than love and time-

‘Cause you 're a dream, moon, but not life

For words bracing frayed warps,

And blue roots you can’t weed out-

Many books later, lights given up for missing

Were found, theirs was a broken idiom

Only souls intend-

No big deal, what mothers simply can’t love

Are unsolved children from fights

Between their wombs, and moon,

Those chatty ladies who can’t wait

To screw up your dinners with endless tales

Of lousy sex, worry, or distress.

*******

But in the cold bleak light from the hall

You simply can’t be a goddess

Looking for fauns or friends,

Nor a maenad uprooting trees, or enemies-

Soul, your anger is a seed, it always

Gives birth to waste, and sour cream,

No need for the old grandma's remedies,

Hurling yourself at hectic days,

Or raising your hand against limbs-

The seed will soon rise up,

And they won’t call you bastard,

Those good for nothing,

Moon, father, mother,

A fibbing mist raiding your life

Whenever you make room

To an absurd white,

To papers encroaching on the walls,

Books writhing on the floor,

Maybe the winter thrust to first births?

No, just a rejected look for you to learn

How to weave time, so cut it out

With angst, and worry,

If the lover of a lost hero gets more to weave,

Or light can’t divert you while dogs,

And nights wipe out passion, or lust-

Even if a party of days and blue bags shakes you up,

Listen to the voices moon is fuddling,

Unsafe breaths, but please don’t go green-eyed on her

When she writes to heaven, so many letters lying

Among corpses, a rubble of stars,

And the absolute faith, no one can grabes first seasons,

Or so says the maddening memory

You can see standing up against a powder blue,

Drop it, be it your model an ambivalent moon

When she dodges the dull blue of the sky,

And those restless bored sahms, falling stars.

*******

Adrenaline high up the sky, you shocked-

Do not bend over me, night,

No need to, you’ve got lovers, right?

Fear, fear always digging her graves, souls,

Cold, and a silence you misplaced so long ago-

Just remove the sounds words echoed

When stalked by water,

Or fighting like no tomorrow with light-

And you, my cold, do not bite me tonight,

No need to, as souls, and a tousled desire

Don’t mind green, or silence-

As soon as they leave give birth

To life, and God, your last resource,

Give the sky his own fire, but, my soul,

Don’t set yourself on fire, not your fault

If days start whirling ‘round you,

Scalds, men, rejections, of no importance at all,

As you chose from the start colours

And plain books, certainly not love, nor limbs,

You just kept slicing shreds from renegade skies,

Dissenters, the lunatic fringe -

That’s why skies can’t grab you on the fly,

Nor can Sahara want you as a prophet-

Just an albedo of words

Breaking through stones, and boulders-

Dunno if she feels like a mother, but you inside

A place where they’re so keen

To come and meet you,

Questions, doubts, slip-ups

In a brand new creation:

A heavenly vault, foliage, that pearly white

Set to strike back at your soul.

Born in Italy some decades ago, Gabriella fell in love with the English language at six, soon after she had started writing poems (in Italian). She has contributed to a number of national and international magazines and anthologies, and is the author of Lo sguardo di Orfeo, L’inverno di vetro, Di altre stelle polari , Casa di erba’, and in English, A Blue Soul and Blue Branches.

Poetry from Andrea Soverini

Flames in the wind Flames in the wind Rising above ashes Dancing alone Irrational sparks of light To show how hard We burn Spitting fire With every breath Consuming anything we touch The wind keeps us alive Marching on fields Of dry hearts Incinerating all Until we become one Exploding light Suffocating air We were once fire And now we are Nowhere

I’m Andrea, in January 2020 I started writing poetry after I had a vision, twice…In this process, I experienced two visions of myself writing, in the span of a month time, and that was a good enough sign to look into it. So, the day after the second vision I started writing poetry.